By Michael Roberts

Meeting the social needs of the world’s population through the production of goods and services depends on the amount of labour employed (in numbers and hours) and on the productivity of those employed. Under capitalism, of course, what matters more is the profitability to the owners of the means of production from employing workers and investing in productivity-enhancing technology. It is a fundamental contradiction of the capitalist mode of production that the required profitability of those owning the means of production becomes an obstacle to the required production to meet the social needs of the billions of humanity (and, for that matter, to sustain the health of the planet and other species).

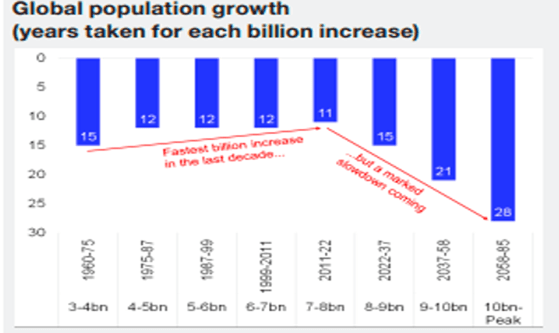

About three years ago I posted some thoughts on the global decline in population growth and the future size of the global workforce available for capital to exploit. It’s worth updating the story. It took until the beginning of the industrial age for the global population to reach a billion and then another century to reach two. That was in 1927. By 1960 the next milestone of 3bn was reached – an interval of just 33 years. Since then, it’s taken only around a dozen years for each incremental billion expansion in world population. There are now 8 billion homo sapiens on the planet.

Dramatic increase in life expectancy has accelerated population growth

The main reason for the acceleration in population during the 20th century was the dramatic fall in mortality, the result of wider application of medical advances like better sewage, cleaner water, vaccinations against raging diseases and effective medicines etc. As a result, life expectancy at birth has increased by around ten years in rich countries. And despite the COVID disaster, which saw a general fall in life expectancy in many countries, the rate is still over 80 in the richer countries.

And even in low-income countries, it has risen to 63, an effective doubling since 1950. This was due principally to dramatic reductions in infant mortality in poorer countries. In 1972, around 14% of Indian and African newborns didn’t survive their first year. Those proportions have since declined to 2.6% and 4.4% respectively.

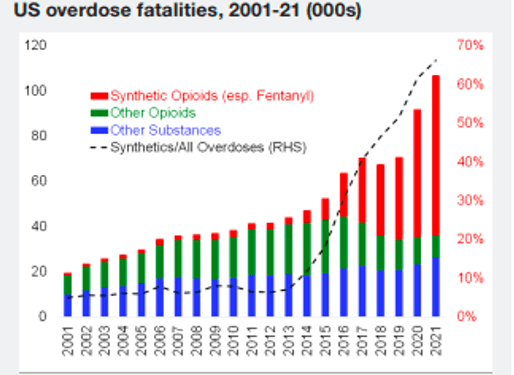

So life expectancy has risen sharply, driving up population. Capitalism however threatens further progress in life expectancy. It’s not just the impact of the COVID pandemic, particularly on life expectancy in the poorer countries. US life expectancy was falling even before the pandemic. According to US Center for Disease Control and Prevention data, more than 100,000 Americans died of overdose in 2021, representing a fivefold increase over the last 20 years. That figure is now on a par with diabetes-linked deaths, which are up “just” 43% over the same period.

US death toll from synthetic opioids has gone through the roof

The US has long suffered an opioid epidemic. This used to account for around half of all overdoses – mostly from prescribed painkillers and drugs like heroin and methadone. But since 2014 the death toll from synthetic opioids, mainly Fentanyl, has gone through the roof. In 2021, they played a role in two-thirds of all overdose fatalities. On current trends it won’t be long before Fentanyl alone claims more victims than diabetes. The difference for life expectancy being that whereas Covid and diabetes generally kill the old, Fentanyl disproportionately affects the young (around 60% of opioid deaths are in those under the age of 45).

The future will see a deceleration of population growth

Indeed, the 21st century marks the peak in the rate of population expansion. According to the UN’s latest projections, it will take 15 years to reach 9bn and then a further 21 years to reach 10bn, before the world population peaks at 10.4bn in 2085.

The driver of this deceleration is a steady reduction in the number of children each woman bears during her lifetime. Over the last half-century, the total fertility rate (TFR) has halved. Again, this is due to medical advances like contraception and urbanization where large families are not necessary to farm the land. Most human beings now live in cities and towns. Global fertility is now down to 2.3 live births per woman. More than half of all countries – including the two most populous nations, China and India – are actually below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per couple. Some territories in East Asia (e.g. Korea and Hong Kong) have a fertility rate below one.

Slowing growth in the working age population

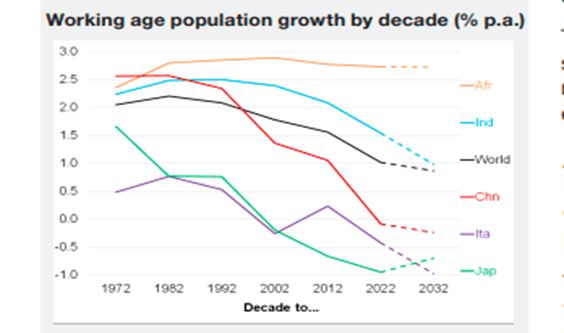

That brings us to the crucial figure for capital – growth in the working age population. In the decade to 2022, the working age population expanded by around 1% p.a. globally. But that was less than half the rate prevailing in the second half of the 20th century. Many large countries will see their workforce decline from hereon. The demographic ‘crisis’ so often referred to for China applies to many other major economies.

The available global workforce for capital is set to decline if current trends continue. Can this be compensated for by faster growth in the productivity of the existing labour force? Well, despite all the promise of the internet age, trend labour productivity growth, as measured by output per hour worked, has actually slowed markedly over the last couple of decades. It now averages just 0.6% p.a. across the bloc of G7 economies. That’s the slowest it’s been in the last half century.

Productivity growth not able to compensate

I have explained the reasons for this general slowdown in the productivity growth of labour in previous posts. The long-term decline in the profitability of capital globally has lowered growth in productive investment and thus labour productivity growth. Capitalism is finding it ever more difficult to expand the ‘productive forces’.

The US economy is the best performer of the major advanced capitalist economies at only 1.4% annual labour productivity growth over the last five years. All others are at a sub-1% annual pace. If we now combine these trend productivity growth numbers with likely working age population growth, we glean an insight into future GDP growth prospects.

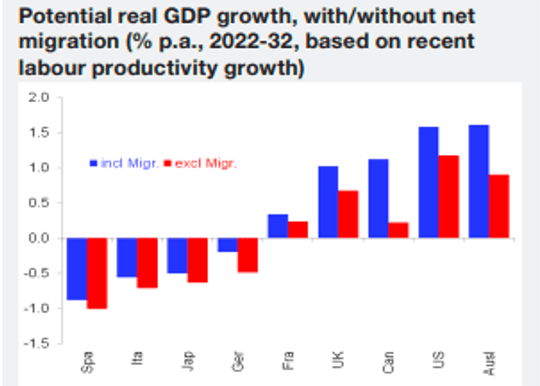

Potential for immigration to increase economic growth

The Anglo-Saxon economies, boosted by net immigration, may be able to sustain positive real GDP growth – but at a pathetic trend rate of 1.0-1.5% (at best), well below 20th century trend. Japan and the Eurozone economies, are heading for a post-growth existence, with trend real GDP contraction of as much as 0.5-1.0% p.a. So if you support the idea of ‘de-growth’, then you will get your wish in those regions over the next decade. And remember, these long-term projections ignore the probability of sharp slumps in production and investment in every decade ahead.

All this suggests that the capitalist mode of production is in a terminal phase. However, there are still areas of exploitation of labour that have yet to be fully tapped by capital.

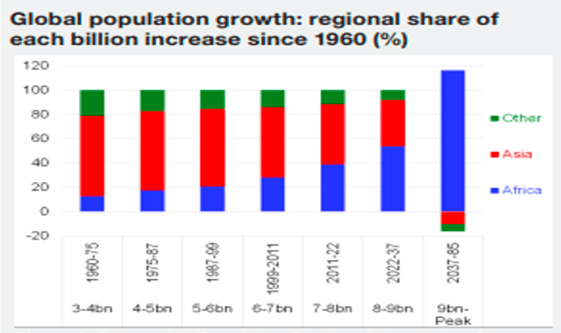

Future population growth rate to be highest in Africa

Half the projected next billion increase in global population in the 15 years to 2037 will be in Africa. Indeed, thereafter, the entirety of net world population growth will be African!

Capital can expand if it can increase value from the exploitation of more labour or increase the rate of exploitation of the existing workforce. The latter is increasingly difficult and growth in the former is decelerating – except in Africa. This continent has suffered centuries of slave exports to the advanced world and the break-up through colonial occupation of its native lands. Now it must face the prospect of increased exploitation of its burgeoning workforce as capital seeks new sources of labour to boost profitability.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.

Featured image: Infographic on future population growth from populationeducation.org.