By Andy Ford

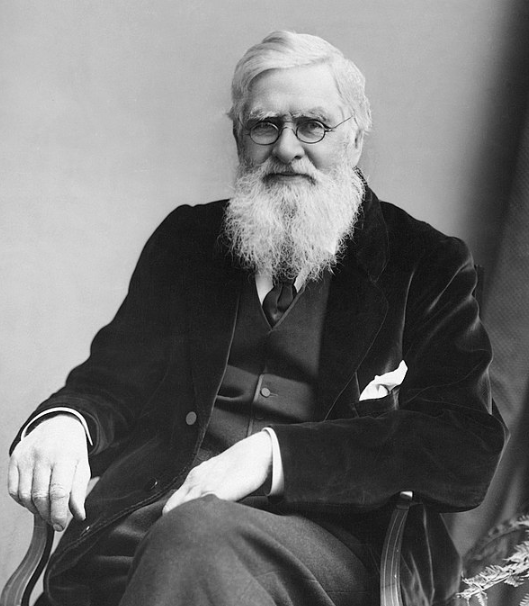

Alfred Russell Wallace, who was born two hundred years ago, is today remembered, if at all, as a sort of shadow of Charles Darwin. But in fact he came up with the idea of evolution completely independently and took a far more progressive stance on social issues of the day.

Where Darwin came from a solid middle-class background, Wallace came from a lower middle-class family whose fortunes were in decline. There were nine children in the family and Wallace had to leave school at 13, to work as a junior surveyor. This was the period when he came into contact with the early proto-Chartists in the Mechanics Institute movement, and which gave his work a life-long slant towards a socialist view – of indigenous peoples, of the British Empire and of women’s rights.

It was while working as a surveyor that Wallace educated himself as a naturalist, inspired by Darwin amongst others. Eventually in 1848 he set out for Brazil to investigate and collect specimens of the wildlife of the region and in 1852 he returned to the UK. But in a devastating accident, his ship caught fire in mid-Atlantic and the collections were destroyed. Wallace nearly died, and he and the crew were adrift in an open boat for ten days.

A lesser man would have given up at that point, but Wallace was undaunted and set off for south-east Asia to explore the islands of Malaysia and Indonesia. One indication of his work rate is that while he was there, he discovered 2% of all the bird species known to science today.

The ‘Wallace Line’

He also noticed that despite the similarity of the climate of the eastern islands of New Guinea, Flores and Timor to that of the western islands of Borneo, Sulawesi and Java, their animal species were completely different. The animals on the eastern islands were predominantly Australian and those on the western islands were Asian. The dividing line is known as ‘Wallace’s Line’ to this day.

Wallace worked out that the emergence of species was clearly due to more than just adaptation to local conditions – there had to be some level of historical determination as well. In his 1876 book, Geographical Distribution of Animals, he argued that the distribution of animal species is determined by an interplay of the Earth’s history and the evolutionary history of the animal species; a far more dynamic view of evolution than Darwin’s one-sided stress on natural selection. In Island Life (1880) he talked about the “complete interdependence of organic and inorganic nature”.

While collecting specimens in Sarawak, Wallace developed an idea that one species emerges from another: “Every species”, he wrote, “has come into existence coincident both in time and space with a pre-existing closely allied species”. He published it in a document known today as The Sarawak Paper (1855).

It was a ground-breaking synthesis of theory and practice, but despite this, it was greeted with indifference. Charles Darwin wrote to Wallace to commiserate, pointing out that at that stage, most scientists did little beyond “…mere descriptions of species”. Wallace’s paper was ahead of his time.

The interest and support given by Darwin probably explains why he sent his next paper, the Ternate Paper (written on the island of Ternate during a bout of fever) to Darwin, rather than just publishing it. Fully entitled On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type, it first put forward the idea of ‘transformation’ of one species into another.

When Darwin received Wallace’s paper he panicked – he had been sitting on a similar idea for years, too worried about an establishment backlash to publish. Now Wallace forced the pace. Darwin wrote “So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed”, but he also said he would rather burn his draft book than behave badly towards Wallace. It was decided that the Linnean Society meeting of July 1, 1856, would receive a double announcement of each scientist’s papers – Wallace’s on the ‘transformation of species’ and Darwin’s on ‘natural selection’ – to give each equal credit.

Wallace’s legacy was not to last

When Wallace returned to Britain in 1862, he found himself wealthy from the sale of his specimens and he was esteemed for his scientific ideas. But whereas Darwin’s fame solidified and grew, Wallace’s was destined not to last. His money was frittered away, and he had to earn a living marking exam papers, until, in the 1880s, Darwin secured him a pension of £200 a year. His scientific reputation suffered by his conversion to spiritualism in the 1860s and he even put forward the mad idea that human evolution was due to the influence of psychic spirits.

But Wallace also championed progressive ideas, perhaps influenced by his youthful Chartist contacts. Because of his prolonged contact with indigenous peoples in the course of his work, he recognised that although they could not quote Cicero or play Chopin on the piano, they excelled in the things that were useful and important to them and they were not “savages”.

He became an anti-imperialist, proclaiming the “right of every people to govern themselves”. In his book The Malay Archipelago, Wallace pointed out the “state of barbarism” prevailing in Victorian England, with its huge social inequality and poverty, which he contrasted with the egalitarianism of the indigenous communities he had seen in Malaysia.

Wallace became President of the Land Nationalisation Society, which campaigned against the huge inequality in land holding in Britain, which continues to this day. He supported votes for women, reform of the House of Lords, green belts around cities and the protection of the remaining common land.

Perhaps because of all this he never became an ‘insider’ in bourgeois society, and whereas Darwin played the establishment game, concentrated on the science, and consolidated his reputation, Wallace’s place in the development of evolutionary theory was gradually written out of the public record.

He was, despite his later indulgence in the ideas of spiritualism and phrenology, someone whose greatest achievements were based on solid practical work and a materialist analysis of the data he amassed. In that regard, he was Darwin’s equal and deserves his place in the scientific record.

Alfred Russell Wallace, January 8, 1823 – November 7, 1913