By Michael Roberts

The Eastern Economics Association (EEA) held their annual conference last weekend. It’s not as large as the huge annual conference of American Economics Association (ASSA), but the EEA does incorporate much more heterodox and radical economic presentations than ASSA.

There were hundreds of papers presented. I shall concentrate on a just a few papers from the sessions arranged by Union of Radical Political Economics (URPE), which were kindly sent to me by their authors.

This blog looks at the opening lecture by Joseph Stiglitz

But in this first of two posts on the conference, I shall look at the opening lecture by Joseph Stiglitz for the 4th Annual Godley Tobin Lecture. Professor Stiglitz is a Nobel (Riksbank) prize winner in economics, former chief economist at the World Bank, former President of the EEA and now chief economist at the think-tank, Roosevelt Institute (its name shows its political orientation). Stiglitz has been a leading critique of mainstream neoclassical economics and advocate of getting capitalism to work for the many not the few.

Stiglitz’s lecture was built around a recent study published by him and Ira Regni at the Roosevelt entitled The Causes of and Responses to Today’s Inflation. After a short critique of neoclassical economics and its failure to explain why ‘the market’ does not avoid shocks and irregularities, Stiglitz concentrated on analysing the cause of the recent spike in inflation since COVID.

As he put it, the rise in inflation has sparked a debate about its causes, with some claiming it is demand-induced, largely the result of high spending in response to the pandemic. Others focus on pandemic-induced supply shortages and demand shifts, possibly exacerbated by market power and market manipulation. While there may be elements of all of these, the policy response needs to address the dominant cause. If it’s a result of excessive aggregate demand, then monetary policy—reducing aggregate demand through monetary tightening—is appropriate. If it’s largely supply-driven, a more tailored response is required, including fiscal policy that alleviates the supply constraints.

Conclusions about the causes of inflation

He concluded that current inflation is largely driven by supply shocks and sectoral demand shifts, not by excess aggregate demand – here Stiglitz disagreed with fellow Keynesian Larry Summers or for that matter former White House economist, Jason Furman, who both blame government spending for creating ‘excessive demand’.

What flows from this is that “monetary policy, then, is too blunt an instrument because it will greatly reduce inflation only at the cost of unnecessarily high unemployment, with severe adverse distributive consequences.”

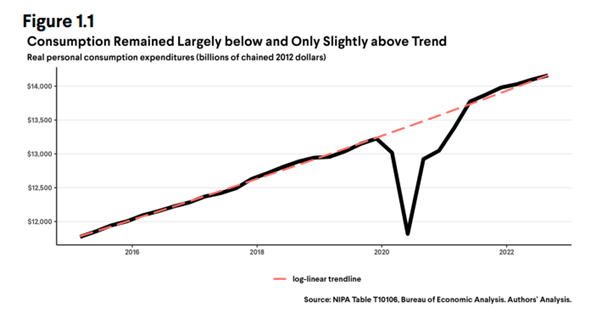

Personal consumption has been below trend

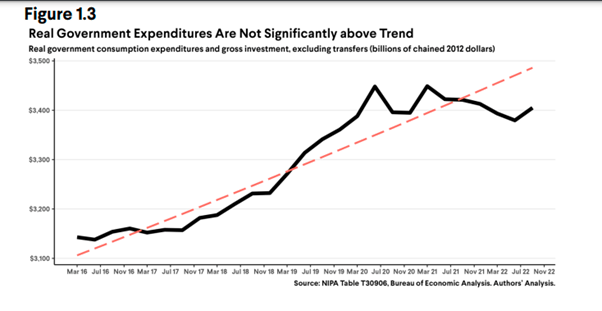

It can’t be excess demand because US real personal consumption has largely been below trend, particularly in the periods when inflation heated up, and total real aggregate demand has been consistently below trend, “which reinforces the conclusion that the “problem” arises from the supply side.”

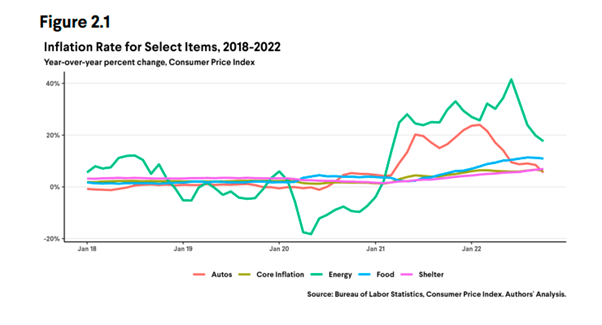

And a sectoral breakdown of inflation, as well as a closer look at the patterns in the timing of inflation, further support the conclusion that excessive spending during the pandemic is not the principal cause of today’s inflation. Breaking down inflation by sector reveals that it is tied to the obvious shocks and supply chain interruptions the economy has experienced, from high food and energy prices to the shortage of microchips for automobiles.

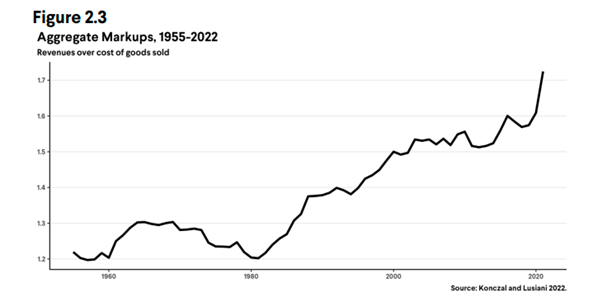

Shortages have allowed companies to hike their margins if they have sufficient market power.

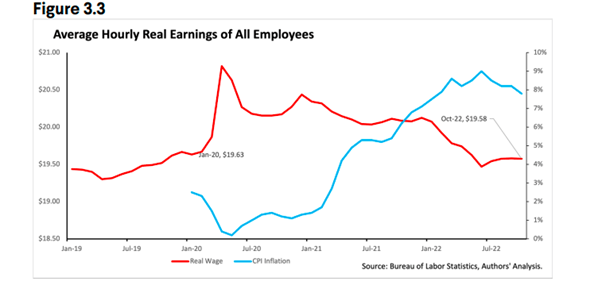

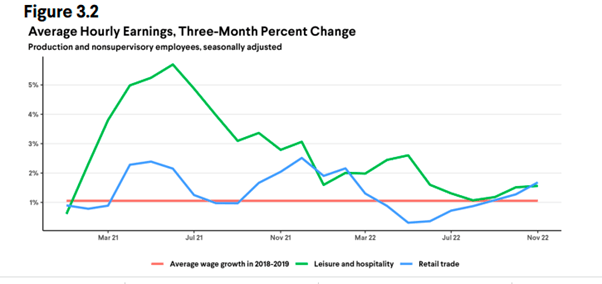

As a result, corporate profits have jumped sharply while wages struggle to match price rises.

Stiglitz denied that there was any sign of a ‘wage-price’ spiral; and the other mainstream explanation of inflation, rising ‘expectations’ of price rises, also appeared to be weak. Indeed, as supply-chain blockages post-COVID and other supply shortages have subsided, inflation rates have started to fall back.

If this analysis is right, then hiking interest rates to reduce ‘excessive demand’ will not lower inflation but instead “induce a major contraction” in the economy that will hit the “most marginalized in society.” This contrasts with those like Jason Furman who reckon inflation is the result of excessive demand and now call for the Fed to hike its policy rate to 6% (I quote from a Furman tweet: “If I were the FOMC, I would be raising rates by 50bp at the next meeting and signaling a terminal rate of 6%”).

Stiglitz’s alternative to hiking interest rates

What was Stiglitz’s alternative economic policy for dealing with high inflation? In answering questions, he advocated changing the Fed’s inflation target from 2% and allowing the target to be flexible and to rise even as high as 5%, which the economy “could live with”, rather than driving the economy into recession.

Fiscal policy should replace monetary policy as the weapon against inflation. But what did that mean? Here Stiglitz was a little vague. He advocated more government investment, particularly in green energy, regulation of monopoly price fixing (although he was opposed to price controls – correctly in my view). He wanted an end to marginal pricing in energy markets which only caused wild swings in energy prices. He wanted a windfall tax on excessive profits. He advocated intervention by government to direct production and resources to reducing supply shortages, perhaps using the Defense Production Act, available in war time to force companies to produce what was needed socially rather than profitably – this would be similar to making big pharma produce vaccines to deal with COVID.

I agree with much of Stiglitz’s analysis of the current inflation spikes and the cost of living crisis – and his critique of monetary policy as the answer (see my many posts on this). And many of his proposed alternative measures would undoubtedly be better than the Fed’s ‘shock therapy’. But there was no mention of taking over the fossil fuel companies and companies that are making huge profits from the inflationary spiral. That would threaten the basis of capitalist production in the US. In my view, without that, a plan of investment and production that keeps employment up and inflation down would be infeasible. Public ownership of the major economies? Politically impossible and unrealistic as a solution, you might say. But no more unrealistic than expecting any current government in the US or in the major economies to resort to Stiglitz’s proposals.

Why were the major economies hit so hard by food and energy ‘shocks’?

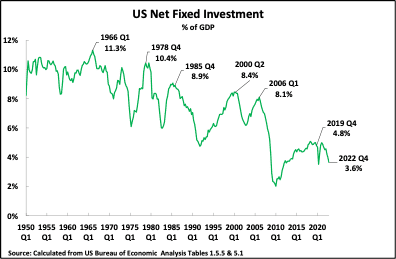

The main issue missing from Stiglitz’s analysis of the causes of the current inflation is the bigger, long-term picture. Why did the major economies fail to cope with the energy and food ‘shocks’ caused by the post-COVID ‘scarring’ of supply chains and trade linkages? In my view, the answer lies in the general slowing of productivity growth and productive investment that has taken place over the previous two decades and particularly in the period leading up to the COVID slump. The major economies not only could not cope with the ‘shock’ of a pathogenic pandemic; they no longer have the dynamism of recovery after a slump, even in the US, to deal with the aftermath.

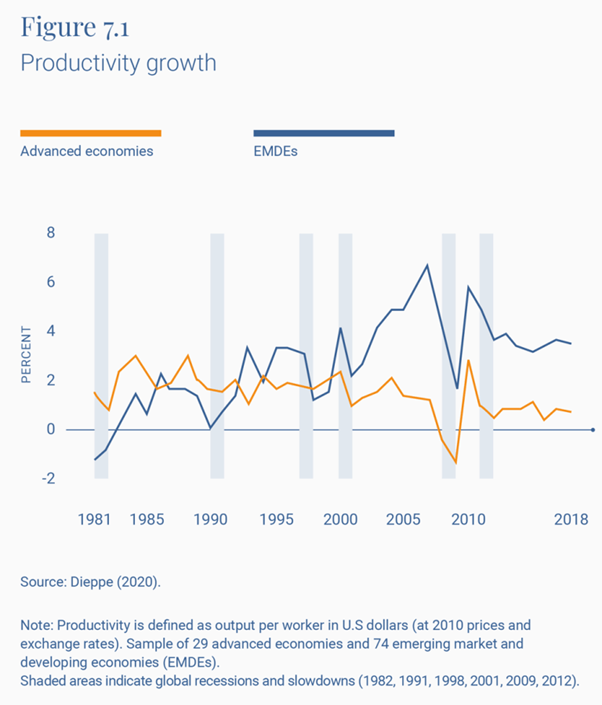

Let me quote from a recent Brookings Institution report on global productivity: “Growth of labor productivity—output per worker—is the single most important source of lasting per capita income growth. Unfortunately, even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, productivity growth had been slowing around the world. In advanced economies, the slowdown continues a trend that has been underway since the late 1990s. In the aftermath of the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have experienced the steepest, longest, and most synchronized fall-off in productivity growth in decades.“

Productivity growth has steadily declined

The figure below shows that productivity growth in the advanced economies has steadily slowed since the late 1990s; the growth in the emerging economies is distorted by high productivity growth mainly in China, but even there that has subsided since the end of the Great Recession.

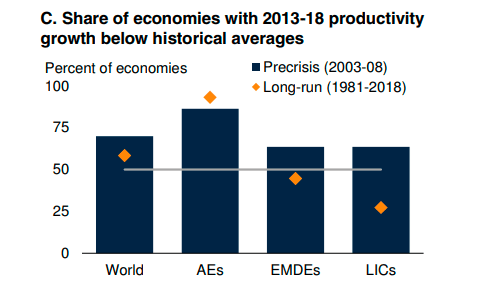

The World Bank has shown that nearly 75% of economies even prior to the COVID slump had average productivity below the long-term average; and in more than 80% of advanced economies.

A recent McKinsey report found that this productivity slowdown has mainly come from a decline in capital per worker and in innovation ie productive investment: “since the Great Recession, capital intensity, or capital per worker, in many developed countries has grown at the slowest rate in postwar history. An important way productivity grows is when workers have better tools such as machines for production, computers and mobile phones for analysis and communication, and new software to better design, produce, and ship products, but this has not been occurring at rates that match those recorded in the past. A decomposition of labor productivity shows that slowing growth of capital per hour worked contributes about half or more of the productivity decline in many countries.”

Long-term decline in profitability

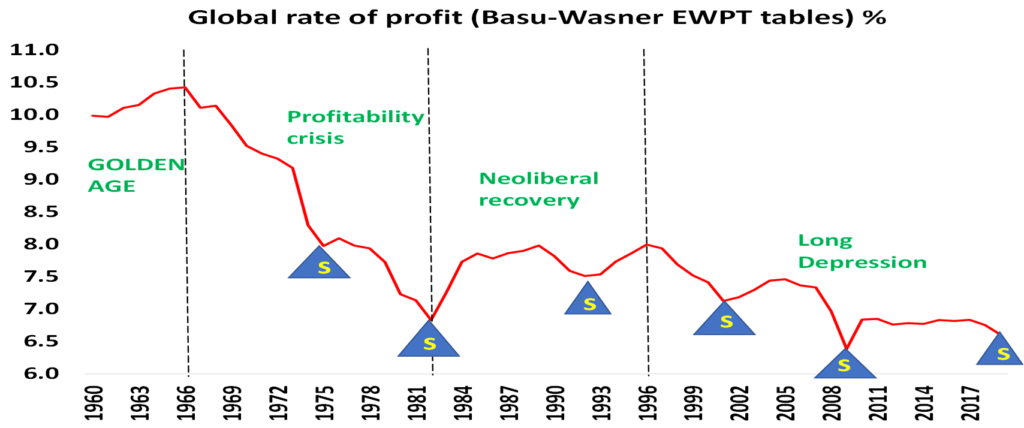

And readers of this blog will know only too well what I think is the cause of this slowing productive investment – it’s the long-term decline in the profitability of productive capital in the major economies (and accompanying recurrent crises – s in the graph below).

As inflation falls back, with the major economies slipping into recession, that will still leave everything as before: low productive investment and productivity growth; and the energy companies, big pharma, the big banks all still in place. So the capitalist ‘market’ economy will face yet more ‘shocks’ to its fictitious ‘equilibrium’ in the future, as long as this fundamental economic structure remains in place.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.