By Michael Roberts

There were some interesting papers presented in the URPE sessions at the Eastern Economics Association conference that ended last weekend (see my previous post). I cannot cover them all but just a few papers that were kindly sent to me by their authors.

Long waves in capitalist accumulation

First, long waves in capitalist accumulation. Professor Jason Hecht of Ramp College presented a paper entitled ‘Are long waves 50 years? Reexamining and updating economic and financial long wave periodicities in Kondratieff and Schumpeter’ (see paper here). Using new data from the Bank of England and the Maddison Data Project 2020, Professor Hecht reckons that, just as the Russian economist of the 1920s, Alexander Kondratieff claimed, there are long cycles in capitalist production of upward and downward phases that last around 50 years from trough to trough. “Our results find a consistent pattern of a fifty-year average long cycle periodicity across macroeconomic variables for the UK as well as for real per capita GDP across the industrialized economies. These cycles or waves are endogenous to capitalist accumulation not something caused by external forces outside the capitalist economy.”

Professor Hecht used Kondratieff’s original data to reexamine his estimates of long wave periodicities by replicating the published econometric models and smoothed residuals to verify specific years of long wave turning points. As a further test, he used “unobserved component model” methods and techniques to extract long wave periodicities from the same time series as well as from new long-term data.

Marx noted the cyclical nature of capitalist production. “All of you know that, from reasons I have not now to explain, capitalistic production moves through certain periodical cycles”, Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels, 1865. And he subsequently spent some time in trying to identify such cycles in the capitalist economy. He wrote to Engels in May 1873 about `a problem which I have been wrestling with in private for a long time’. He had been examining `tables which give prices, discount rate, etc. etc.’. `I have tried several times –- for the analysis of crises –- to calculate these ups and downs as irregular curves and thought (I still think that it is possible with enough tangible material) that I could determine the main laws of crises mathematically.”

Different lines of attack on the idea of long waves

Long waves or cycles have been greeted with much scepticism by many Marxist economists. Kondratiev’s own ‘long cycles’ have been attacked at three levels. First, it is argued that there is no firm statistical evidence that such cycles of 50 years or more really exist. Second, Kondratiev’s argument that cycles should be considered endogenous to the capitalist mode of production has been rejected. The alternative consensus is that changes in the relative pace of economic growth or in prices of production are caused by external factors like wars, revolutions, disease, weather or more specifically new stages of capitalist economic organisation (imperialism, financialisation etc). Third, there is no convincing theory or model to explain these long cycles, if they do exist.

Kondratiev defended his theory of long cycles from all these criticisms. He admitted that the available data were inadequate to “assert beyond doubt the cyclical character of these cycles. Nevertheless, the available data were sufficient to declare this cyclical character to be very probable”. In particular, the time series for prices of production and commodities bore the greatest support for cycles “and cannot be explained by external random causes”. Professor Hecht’s paper goes some way to refute the first two of those arguments and support Kondratieff.

Subsequent work by Marxist economists have, in my view, gone on to refute the third argument against long waves or cycles. Ernest Mandel emphasized the connection between the laws of motion of capitalist accumulation and the rate of profit: alternating long phases of accelerated and decelerated accumulation are tied directly to corresponding fluctuations in the rate of profit. Anwar Shaikh also took up the cause, with the difference that long waves were not just based on up-and-down movements in the rate of profit, but on Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall secularly.

Further defence of the ideas of long waves

More recently, Lefteris Tsoulfidis and Persefoni Tsaliki also connect the long–term movement in profitability with phases of long cycles, empirically supporting this with data on the profit rate from various OECD economies. In my own work (The Long Depression, chapter 12), I argued something similar with evidence to show the connection between a 32-36 year cycle in profitability being at the core of the longer swings of K-cycles. Where there are differences among these authors is on the length of the K-cycles (which I think have been getting longer) and what current phase and cycle capitalist economies are in.

Why does this matter? Well, if there are identifiable long cycles and there is a coherent endogenous model behind them, then we can better understand the ‘health’ of capitalism. Shaikh, for example, reckoned that the first decades of the 21st century were a downphase and so predicted the Great Recession. I did something similar in 2005: “There has not been such a coincidence of cycles since 1991. And this time (unlike1991), it will be accompanied by the downwave in profitability within the downwave in Kondratiev prices cycle. It is all at the bottom of the hill in2009-2010! That suggests we can expect a very severe economic slump of a degree not seen since 1980-2 or more” (written in 2005, The Great Recession). While Shaikh and I reckoned this downphase would end in 2018 at the latest, Tsoulfidis and Tsaliki reckon the current cycle downphase would last until 2025 – and they seem to be right.

Professor Tsoulfidis also presented at EEA, not on long waves, but on whether the neoclassical marginal productivity theory of capital was empirically valid. Using input-output tables and some very complicated (for me) statistical analysis, Tsoulfidis showed that the equality of marginal productivity of a factor of production with its payment results from an identity, and not from any causal relationship from the marginal product of capital to the rate of profit as argued in the neoclassical theory. The rate of profit is determined in a different way – the Marxist one being through the rate of exploitation of labour and the accumulation of means of production relative to labour.

Drop in Britain’s rate of profit was offset by colonial rule in India

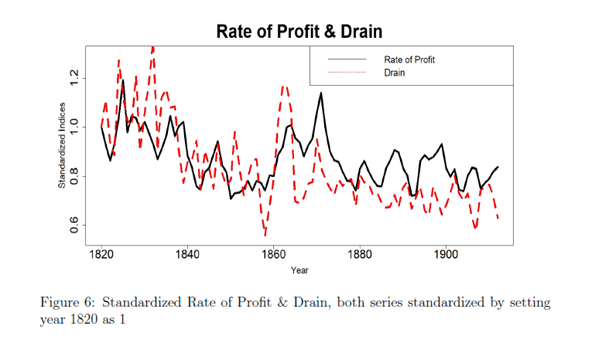

Kabeer Bora of the University of Utah made a novel attempt to measure the transfer of value appropriated by Britain from its ‘jewel in the crown’ colony India during the 19th century. Bora reckoned that this transfer of surplus value was invaluable for the success of the British economy. In his analysis, he relied on Marx’s law of the falling rate of profit, namely that as the rate of profit fell domestically, British capital counteracted that with increased profits drained from India. In Marx’s own words: “foreign trade partly cheapens the elements of constant capital, and partly the necessities of life for which the variable capital is exchanged, [thus] it tends to raise the rate of profit by increasing the rate of surplus-value and lowering the value of constant capital. It generally acts in this direction by permitting an expansion of the scale of production. Bora measured the drain of value from India to Britain using the ratio of the India’s nominal exports to nominal imports to and from the UK. He found that an increase in this colonial ‘drain’ of 1% increases the rate of profit of Britain by around 9 percentage points.

So not only did colonialism help Britain but it was particularly the drain of resources from India that did so.

The inflationary puzzle

Matias Vernengo of Bucknell University presented a thought paper on what he called the Inflationary Puzzle. Venengo argued that the current inflationary burst was not the result of excessive government spending, but the “real culprit is the breakdown in supply chains”. So he reckoned that “stagnation, not inflation, is the bigger danger facing the economy”. Readers of this blog know that I also reckon the current inflationary spike is due to supply not demand factors.

I particularly liked Vernengo’s sceptical view of the post-Keynesian explanation of inflation: oligopolistic price hiking. Vernengo reckoned that this “misses the role of cost-push inflation, and, more important, it disregards the role of distributive conflict at the heart of heterodox views of inflationary processes”. He also threw cold water on the consensus view that the sharp hikes in interest rates and monetary tightening imposed by Paul Volcker as Fed Chair in the late 1970s worked to crush inflation then. “In reality, it was the restraining of workers’ demands and the attenuation of the distributive conflict that mattered.” I agree and I am reminded of what British economic adviser to Margaret Thatcher, Alan Budd said at the time. “There may have been people making the actual policy decisions… who never believed for a moment that this was the correct way to bring down inflation. They did, however, see that [monetarism] would be a very, very good way to raise unemployment, and raising unemployment was an extremely desirable way of reducing the strength of the working classes.”

Socialist planning with markets?

In a session on socialist planning, Al Campbell of the University of Utah argued that we should not equate a ‘market economy’ with capitalism because “while markets are necessary for the circuits of capital by which capitalism carries out its standard form of exploitation, markets are specifically not where exploitation occurs (total social profit does not come from trade.” A market system does not involve exploitation of labour as such; that is a capitalist system of production. So there is nothing in the use of markets as a tool for allocation for social production that violates any principle of socialism.

Al concluded that “as part of building a socialist society with its goals (human development, etc.), markets are a possible tool”. This seemed to be a revival of what used to be called ‘market socialism’ from the likes of Oscar Lange in the 1970s. I am not sure that we can accommodate markets in socialism if we mean price competition among producers to make things and services we need. I cannot see that as part of socialist direct production to meet social needs free at the point of use. And if we mean by ‘the market’ that we can using pricing to maximise ‘efficiency’ and reduce labour time, then again, using labour time units of account seems more to the point than ‘market pricing’.

Technology’s role in socialist planning

Finally, Guney Isikara and Ozgur Narin of City University of New York argued that planning techniques are not enough to ensure the development of socialist production and distribution. Socialism may “require the abolition of the law of value as well as private property in the means of production, but is not granted by this abolition. The empowerment of workers is not an outcome of the advancement of productive forces, but is rather a significant element of the latter.”

Both the flat rejection of new planning tools and techniques and their uncritical glorification as miraculous saviours share the common mistake of attributing innate characteristics to technology and disregarding the underlying social relations. “The tension between necessity and freedom, between society and non-human nature, will not (and cannot) be ultimately reconciled. Yet it will now constrain and be steered by a collective of workers organized in councils, freed from competitive pressures, disenchanted with accumulation, and empowered to shape both ends and means in the light of the fullest possible knowledge of the consequences of their actions. Technology can immensely facilitate all this, but only so long as it is not turned into a black box.”

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.