By Sue Denham

Capitalism, it was once observed, is horror without end. Capitalism is based on the systematic exploitation of the many by the few and that exploitation, which is enforced ultimately with violence, leads to poverty, insecurity, and desperation among the many while it creates opulence and wealth unimaginable in any other era for the few.

The capitalist system isn’t just built on injustice, it is in the DNA of every fibre of every block and brick that imprisons the working class in capitalism. Key to the functioning and smooth running of the system are unequal relationships, such as between workers and bosses, where one side has and exercises the power and uses that to exploit the powerless, we see that so regularly under capitalism that it has largely ceased to be noteworthy.

Only when those with power possess such vast authority over the powerless that it ceases to be merely an unequal relationship and becomes outright oppression, do we really take notice. There are many groups of people oppressed by capitalism, but the largest and most long standing are women.

The oppression of women dates back to the breaking up of the older societies in antiquity, based on communal ownership of the production and distribution of food and other necessary goods, and the creation of new forms of private property, in the ownership of the crops and animals that were used in primitive agriculture.

Unpaid work throughout all recorded history

It could be argued, although now it is an academic question, that without the oppression of women, their exploitation and unpaid work throughout all recorded history, a system of private property in the means of production, distribution and exchange would not even have been possible at all.

Any society which claims to be called civilised should be judged on the yardstick of how that society treats women. Nearly a century ago, women in the UK weren’t allowed to own property, serve on a jury, open a bank account, drink unaccompanied in a pub or work in a legal or civil service job, or even be able to decide for themselves how to exercise their reproductive rights.

We are often told by establishment historians that after the First World War, in gratitude for the labours and sacrifices women had contributed to the war effort, the men of parliament had a revelation about the oppression of women and magnanimously granted them complete equality with men, and that all those injustices were swept away

Obviously, this is not true at all. Even in 1918 they did not grant voting rights to all women; there was a property-owning qualification and a higher age threshold for women seeking to vote. All of the gains women have made to extend their rights under capitalism have been won by women themselves in the teeth of stubborn and often ruthless and relentless opposition from the establishment, who try to cling on to their right to oppress women.

Increased role as wage workers

That seemingly so much progress has been made in, relatively speaking, such a short period of time, is due to one important factor: the increased role of women as wage workers, by which we mean female proletarians. Of course, women have always worked, relentlessly and unceasingly, from “when Adam delved and Eve span”. Even to this day, according to most surveys, women perform most of all domestic tasks. But, with the entry of women into industrial jobs, what became decisive was, how they worked and what they worked at.

Capitalism as a system is based on the creation of profit, which is created by paying the workers who actually produce commodities, less than the value of the labour time embodied in these commodities. There are two main ways to increase profits: by reducing the share of the value that workers receive from their production of commodities, by making them work harder – producing more commodities for the same wages – or by increasing the total number of workers the capitalists are exploiting.

So employing women workers in the production of commodities, and thus creating female proletarians, represented for the capitalists a double gain. It increased the number of workers exploited, and also, due specifically to women’s oppression, they could be paid less than their male counterparts and thus exploited more fully.

So in a development that is paradoxical to most historians, instead of women entering the workforce leading to a general withering away of the oppression of women in society, it has in fact led to renewed attempts on the part of the capitalist class to increase that oppression, as greater freedom and equality for women represents a threat to the profits of the capitalist class.

This factor explains the misogyny and sexism that prevails in most areas of public life and in particular at the top of capitalist society, among those who set the tone to be followed by their acolytes in politics and the media who enable exploitation and oppression.

Bitter and entrenched opposition

That women workers have made such strides of progress in the face of such bitter and entrenched opposition to their liberation, is a great tribute to their marvellous capacity for struggle and self-organisation. Women entering the capitalist workforce gained enormous confidence from having their own pay packets, freeing them from dependence on the men in their lives, and also being together with other women workers in a collective workplace.

Up until the time when they began to be employed in factories in large numbers, most women who were employed outside the home were domestic servants, who were treated abysmally. Individual workers are isolated and atomised and largely powerless to prevent the worst excesses of exploitation. What changed was the scope for self-organisation and the new atmosphere of confidence and collectivity it enabled.

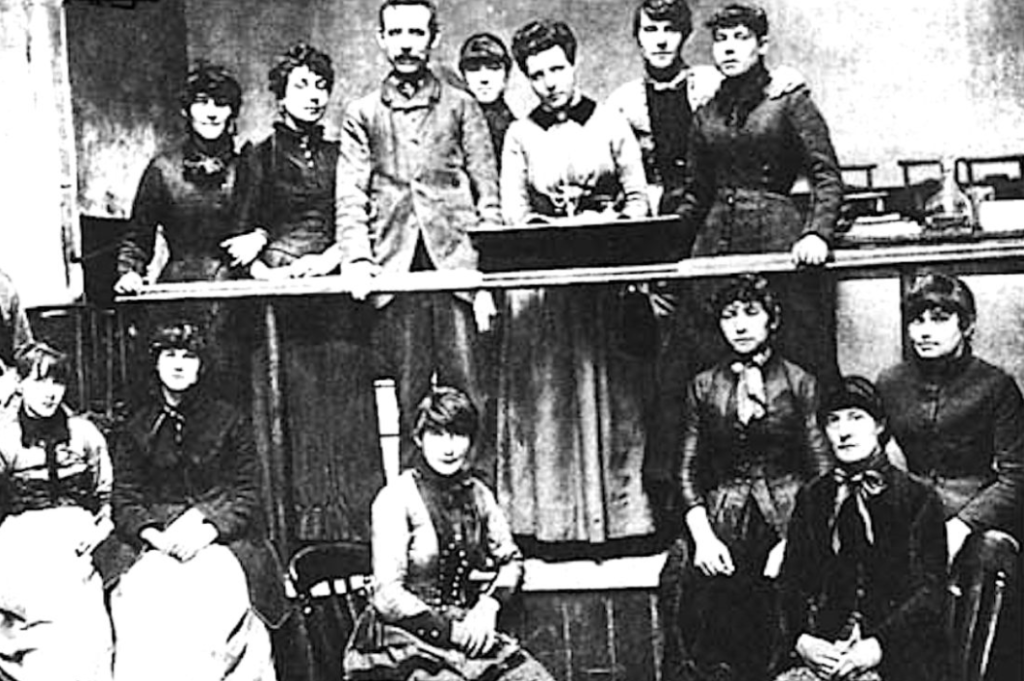

There are too many examples of the struggles of women workers, to mention more than a few of them here. One of the first and most inspiring example of the entry of women into the collective struggle of the working class was the match girls’ strike of 1888. A social reformer, Annie Besant, wrote an article in a small halfpenny paper, The Link, highlighting the appalling conditions and the atrocious treatment meted out to the women workers at the Bryant and May match factory in Bow, East London.

This article so angered the owners that they made the stupid blunder of believing they could coerce their docile female workforce into signing a letter dismissing the claims made by the article. When one worker refused, she was sacked on the spot, although on another pretext. The 1,400-strong workforce refused to accept this sacking and walked out en masse, forcing the owners to reinstate the sacked worker. The discovery of this hitherto unguessed power that they possessed, led the women workers to draw up a list over the next two weeks of the grievances that they faced, and they demanded that these be remedied; when they were not they took industrial action.

‘striking the sails’ became ‘strikes’ of labour

Thus they popularised the term, “strike” originally taken from the act of sailors striking the sails and becalming ships. This was also the name for the act of lighting a match and became from that point on the main term used for the tactic of withdrawing labour, popularly known as a turn out by the Chartists and their descendants, for example, at the time. That these women, who mostly had no formal education, and many of whom were not much more than 14 years of age, had developed the tactic to such a level that any industrial dispute is known as a “strike” even to this day, is a great testament to the impact they made.

Pickets and picketing became common

The dispute was run with an elected committee of three women, Sarah Chapman, Mary Cummings, and Mrs Naulls, delegated to negotiate with management. They then reported back to mass meetings of the whole workforce.

They also instigated the practice of having a line of women workers standing outside the factory, ready to persuade other workers not to take their jobs, a practice that became known as “picketing” after the “picket” of matches that stood in a line they had made in a matchbook.

The term originated to describe a line of wooden stakes driven into the ground, a picket fence, and had also been used to describe a line of soldiers in a forward position guarding against intruders. Now, however, it has developed into common usage, and has become synonymous with the practice of picketing workplaces by striking workers. You can almost picture the wag in the crowd calling out “Look everyone! A picket of match…girls”

As well as their innovating the tactics and terms for industrial actions, they also went far and wide, appealing to fellow workers directly, not only for donations, but for solidarity and urging those unorganised workers to follow their example

Thus, they began the movement of ‘New Unionism’, followed in the next year by the mostly male gas and dock workers of East London, who emulated the match girls’ tactics in the management of strikes. So the match girls’ strike was itself an inspiration that gave an impetus to the modern trade union movement. That is their legacy to us, and it is now our task to carry that same struggle onwards.

UNISON, possibly the largest self-motivated women’s organisation

It is in the trade union movement that the key forces who will take forward the issues of women’s liberation are to be found, among working class women acting in concert with their brothers, the male trade unionists. Unison, with its nearly one million female members, is possibly the largest self-motivated organisation of women in the world, by which we mean an organisation that women have voluntarily joined to safeguard their own interests.

As Such, the unions should be the standard bearers of women’s liberation. Many other trade unions in the UK and beyond have hundreds of thousands of women members, and these women possess not only the organisational ties to male workers with which to convince them of the correctness of their case, but would also be able to bring about their active support and solidarity.

Industrial and economic power

Through the unions, women workers also have the industrial and economic power that they can use to bring to bear on the capitalist system which stands in the way of women’s full emancipation. It is no coincidence that the high points of the feminist movement, from the 1960s to the 1980s, coincided with the moves by organised women workers to redress the wrongs they were labouring under in the workplace, proving that a woman’s place is truly in her union.

Join a union! Go to meetings, talk to your friends, workmates and family and win them to your cause. Do what you can, the working class moves forward together. Every single step forward by every single member of our class brings us closer to our goal of ending exploitation and oppression for ever and creating a world where every member of the human race, man, woman and child, will be free to fulfil their true potential. Where finally we will have a truly civilised society when women will be respected and valued for the great contribution they make to the richness and joy of life.

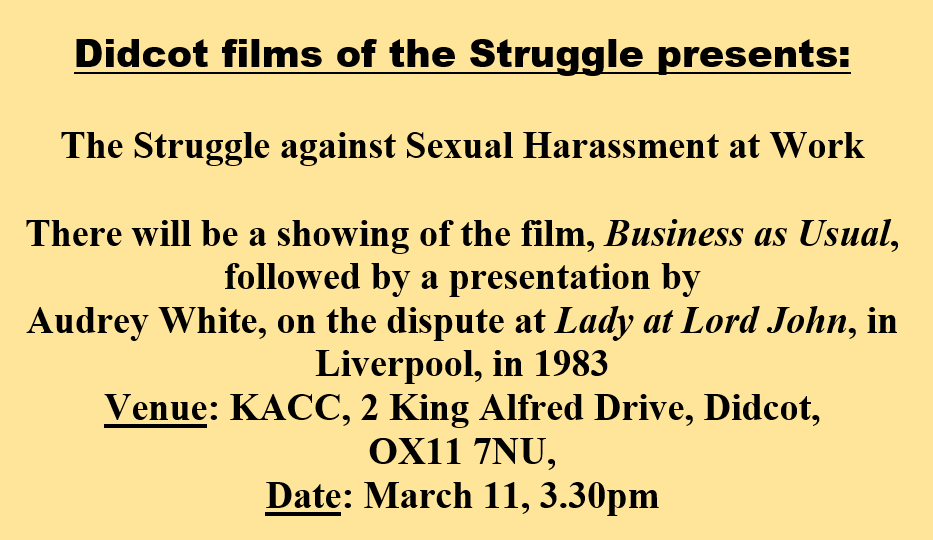

Read an assessment of the Lady at Lord John dispute, Liverpool, 1983, here.