By Michael Roberts

This article was originally published on 5 March 2023, the first day of China’s annual National People’s Congress, by Michael Roberts on his blog.

The annual National People’s Congress kicked off today with outgoing premier Li Keqiang announcing a 5% real GDP growth target, down from 5.5% before. The priority, said Li, was the economy, but even so defence expenditure was to rise by 7.2% in 2023. Li set a target for China’s budget deficit this year at 3% of GDP, while pledging to create 12mn new urban jobs and keep the unemployment rate at roughly 5.5%. He said China needed to “expand market access” for foreign investors, ‘prop up’ consumption and control risk in the real estate sector.

On China’s stricken real estate sector, where many companies have defaulted on their debt, Li pledged to help “high-quality, leading real estate enterprises” while continuing to “prevent unregulated expansion”. Some Western ‘experts’ were mildly positive. “I think on the whole the report is geared towards reassuring foreign investors that China is still a good place to do business and so forth,” said Willy Lam, an ‘expert’ in Chinese politics at the Jamestown Foundation think-tank in Washington.

President Xi is taking an unprecedented third term and replacing Li with Li Qiang, a close associate who presided over the lockdown (mess) in Shanghai last year, as the city’s Communist party chief. He previously worked with Xi in Zhejiang province in the 2000s. The Chinese president completed a clean sweep of the Communist party’s top decision-making body, the seven-member Politburo standing committee, in October.

Western ‘experts’ predict economic woes in China

As the NPC begins, once again, Western ‘China’ experts and even many in China itself predict stagnation and even a crash, as the indebted property sector implodes. China’s population growth has stopped and the workforce is in decline. Growth is slowing. China has entered a ‘middle-income trap’. Indeed, given the huge debt levels in all sectors, China is going to stagnate like Japan has done in the last three decades. The only way to avoid ‘Japanification’, say these experts, is to ‘rebalance’ the economy from ‘over-investment’ and ‘exports obsession’ to a domestic consumer-led economy as in the West and also reduce the state control of the economy so that the private sector can flourish.

Now I have discussed the validity of these arguments at length in various posts and I refer my readers to these in explaining why much of this ‘expert talk’ is not right.

But given the NPC meeting and the new guidelines being set by the Communist Party of China (CPC) leaders, let me go over a few of my arguments against the ‘experts’.

Tackling the arguments of these ‘experts’

First, let’s remind ourselves of China’s past economic performance. China’s growth rate over the last 20 years alone has been significantly higher than any in the G7 and even in the major ‘emerging’ economies, the so-called BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa). And this faster growth rate has been in the most populous country in the world, not some tiny city state, like Singapore, or even slightly larger Asian economies like Taiwan or Korea. There is just no comparison.

Ah, but you see, that’s all over now. China’s growth will now slow to a trickle as in Japan because it overloaded with excessive debt and because it has not rebalanced the economy towards “the consumer”.

This last argument is particularly galling to me. Western experts and even Chinese economists parrot out this argument, which comes straight from neoclassical economics and what left Keynesian economist Joan Robinson called ‘bastardised Keynesianism’ – bastardised because Keynes himself emphasised the role of ‘aggregate demand’ which included investment and not just consumption. And yet the mainstream argues that what matters in a modern economy for growth is boosting consumption.

This argument can be shown to be nonsense. It’s productive investment that is the driver of growth in an economy and from that investment flows consumption – not vice versa.

Arguments about personal consumption growth

The usual basis for the ‘rebalancing’ view is that personal consumption rates are too low in China and this will hold back demand-led growth. For example, take this view by Chen Zhiwu, a professor in Chinese finance and economy at the University of Hong Kong. Chen argues that, under Xi, major reforms towards a larger private sector, consumer-led economy have been sidelined. “The 60 reforms would have largely expanded the role of consumption and private initiatives,” he says. “However, the market-oriented reform agenda has been largely sidelined … resulting in a larger role for the state and a shrunken role for the private sector.” According to Chen, this will mean China’s economy will stagnate from hereon.

Another prominent and widely-followed Western analyst, Michael Pettis, who is based in Shanghai, makes a similar argument, namely that what will push China into Japanese-style stagnation is the failure to expand personal consumption and continue to expand investment through rising debt. And Keynesian guru Paul Krugman joins this chorus, talking of China’s “wildly unbalanced” economy, which Krugman claims: “For reasons I don’t fully understand, policymakers have been reluctant to allow the full benefits of past economic growth to pass through to households, and that has led to low consumer demand.” Unfortunately, sections of the Chinese leadership, particularly their economists in the finance sector, accept this annoyingly stupid argument from the Western experts.

How can anybody claim that the mature ‘consumer-led’ economies of the G7 have been successful in achieving steady and fast economic growth, or that real wages and consumption growth have been stronger there? Indeed, in the G7, consumption has failed to drive economic growth; and wages have stagnated in real terms over the last ten years (and are now falling), while real wages in China have shot up. Moreover, these consumer-led economies have been hit by regular and recurring slumps in production that have lost trillions is output and incomes for their populations.

Relative rates of investment

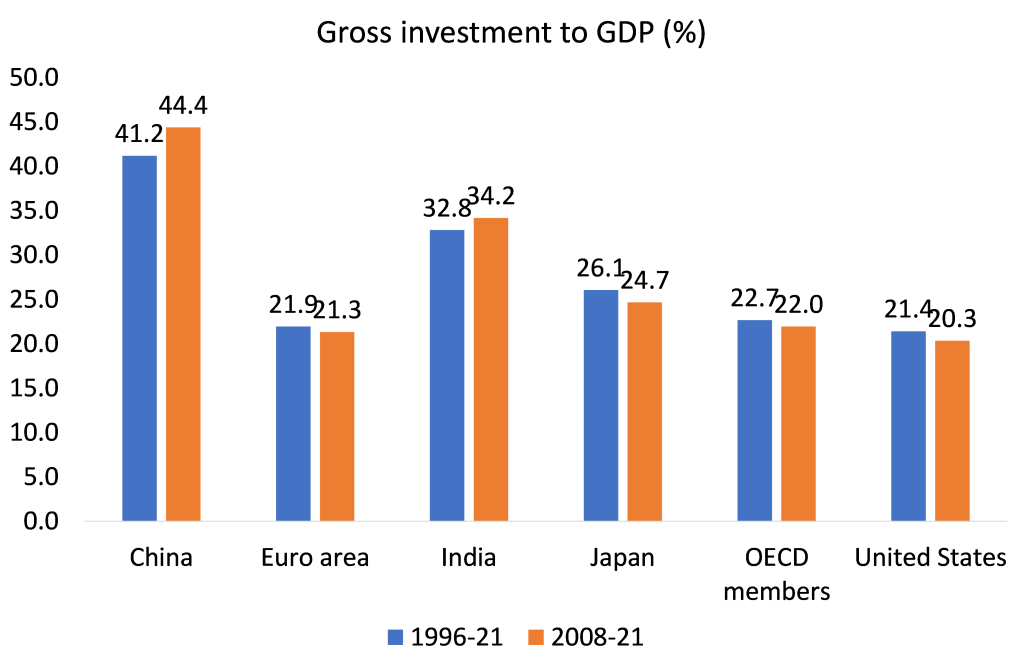

There are two points here. First, investment-led economies actually deliver faster growth in consumption. China has the highest ratio of gross investment to GDP among the major economies (all data from hereon come from the World Bank).

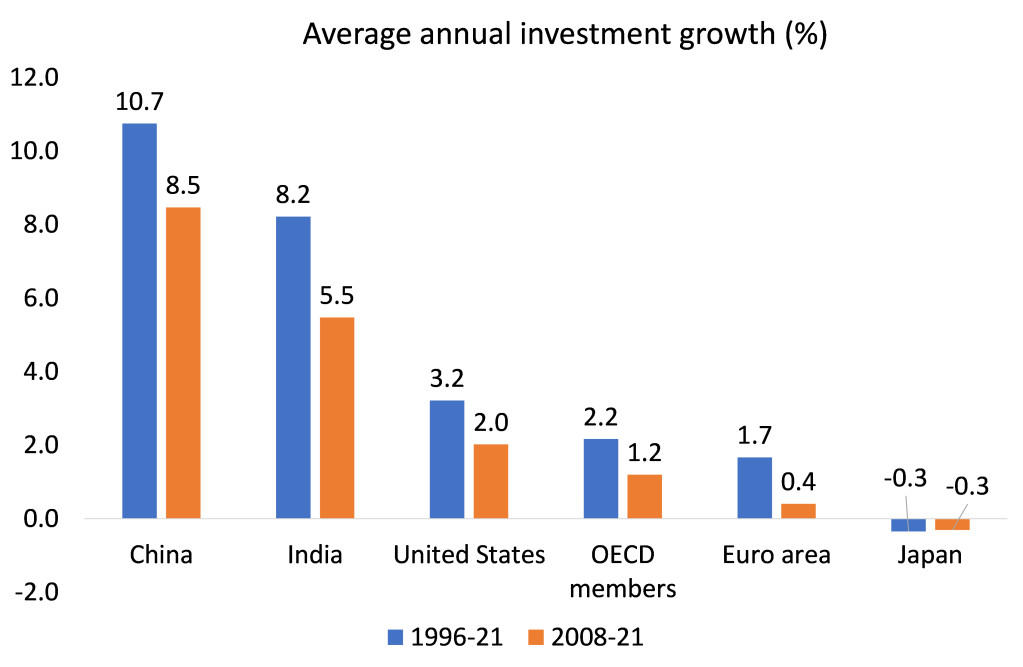

And investment growth is also the fastest.

Sure, investment growth is slowing in China, but the slowdown is even worse from a low level in the G7 economies. ‘Japanification’ actually means falling real investment growth. China is nowhere near that.

Relative growth of China’s economy

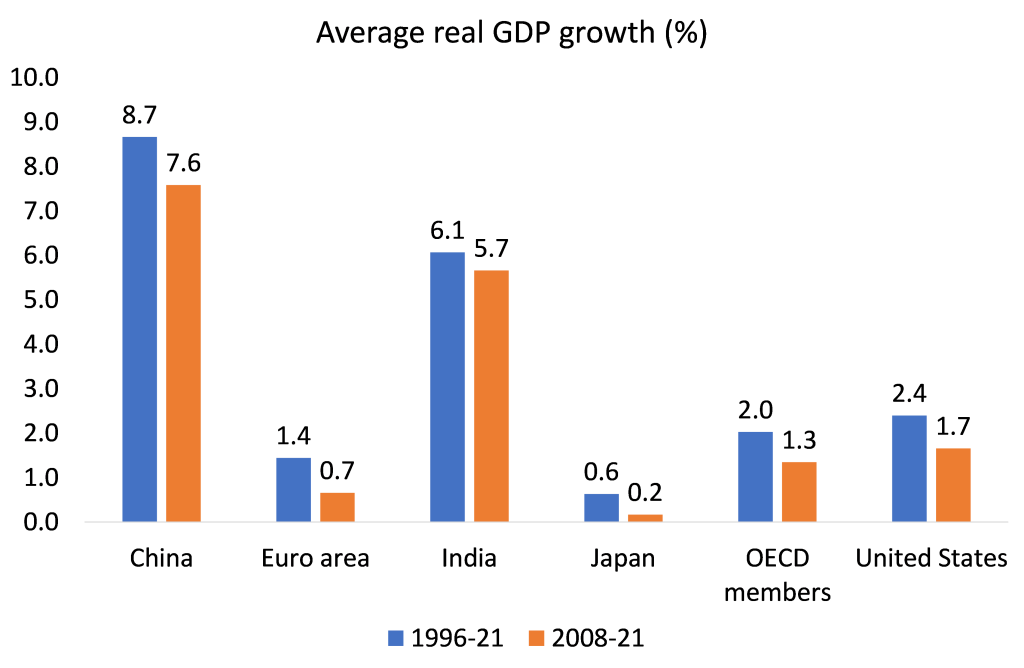

What does this mean for GDP growth? China’s ‘over-invested’ economy has grown more than four times faster than the consumer-led OECD economies and 40% faster than India.

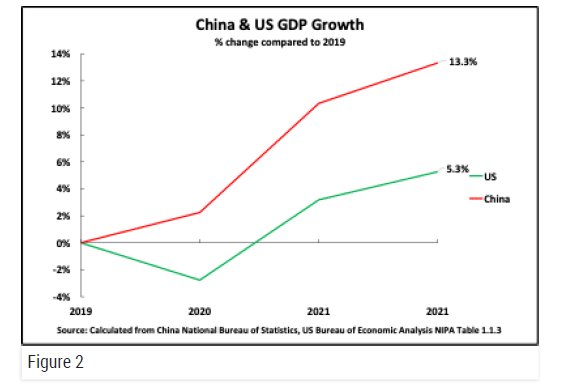

Much was made of the zero COVID ‘disaster’ policy in China. But apart from saving millions of lives, China still did not enter a slump in 2020 unlike all the G7 economies in 2020.

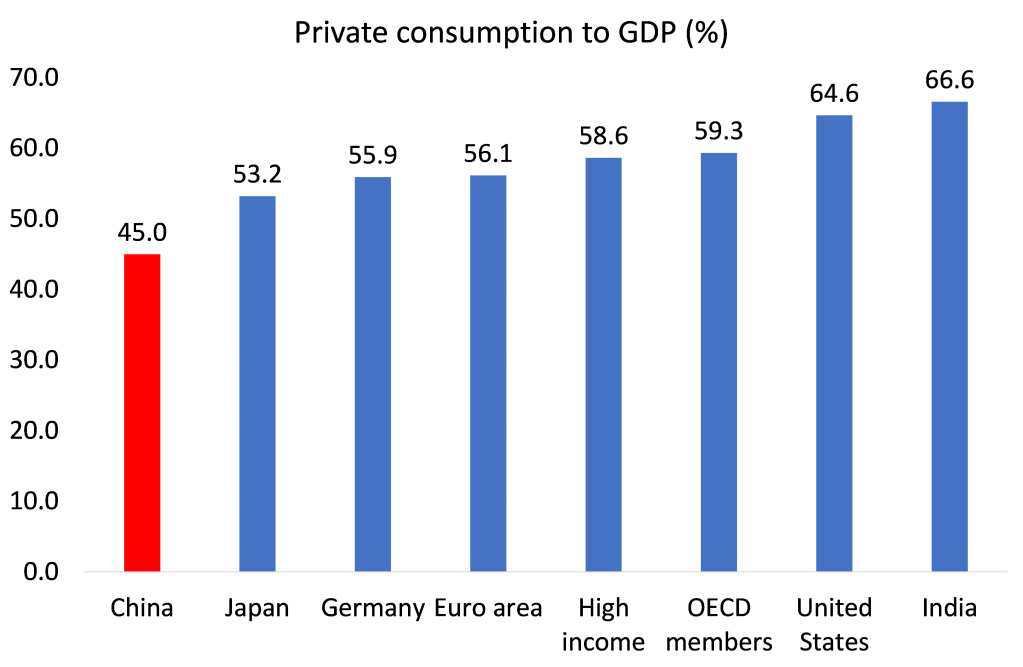

Second, does this mean that consumption in China by households is too low or even falling? At this point, the China experts trot out this graphic.

Then the argument comes: China needs to get its consumption share up to Western levels or it will not be able to grow and stay locked in a ‘middle income’ trap.

Personal consumption growth by country

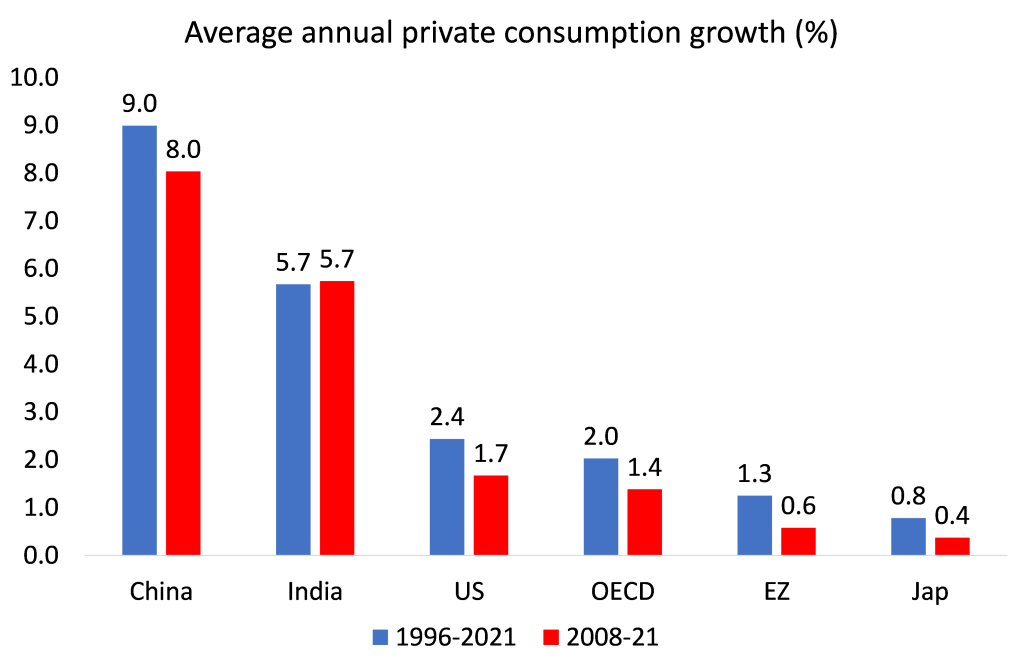

But this is not the graphic that tells the real story. This is the graphic that does.

Surprise! The ‘over-invested’, ‘wildly unbalanced’ Chinese economy has delivered by far the faster consumption growth for its people – nearly four times faster than the consumer-led US, nine times faster than Japanification and even 50% faster than India. What this suggests is that if China were to ‘rebalance’ its economy towards the consumer and reduce investment; and also reduce the public sector and ‘free up’ the private sector (the sector that provides most consumer goods in China), China’s growth rate would fall even more than it has done in recent years!

As it is, the consumption to GDP share graph is misleading. First, this measure of consumption excludes the social wage, particularly health and education, social care and public services. In countries like the US, much of this social consumption has to be paid for and so appears in the consumption share. That is not the case for much of social consumption in China. China has a long way to go in social consumption, but it is way ahead of its emerging market peers in many areas and not so far behind leading G7 economies, who started more than 100 years before.

Second, the graph shows consumption as a share of value-added (GDP) ie to the ‘final consumer’. In the US, consumption would seem to constitute 70% of GDP. However, if you look at ‘gross product’ which includes all the intermediate value-added products not counted in GDP, then consumption is only 36% of the total product; the rest constitutes demand from capital for parts, materials, intermediate goods and services. It is investment that is the swing factor and driver of demand, not consumption by workers.

Productive investment growth has fallen back

What is true is that ‘productive’ investment growth has fallen back in China. Investment in new technology, manufacturing etc has given way to investment in unproductive assets, particularly real estate. In my view, successive Chinese governments made a big mistake in trying to meet the housing needs of its burgeoning urban population by creating a housing for sale market, with mortgages and private developers being left to deliver. Instead of local governments launching housing projects themselves to house people for rent, they sold state assets (land) to capitalist developers who proceeded to borrow heavily to build projects. Soon housing was no longer “for living but for speculation” (Xi quote). Private sector debt rocketed – just as in the real estate bubble in the West. It all came to a head in the COVID pandemic as developers and their investors went bust.

The real estate crisis has remained unresolved. It is interesting to see what the Western experts reckon is the solution. This is what Michael Pettis says: “Unfortunately, it will require a revival of speculative buying to prevent further contraction in the property sector and real estate prices, something which would only make things worse in the medium to long term.” (Tweet, 5 March). So the answer to the property crash is more speculation even if it makes things worse in the future!

That’s not my solution. What the Chinese government needs to do is take over these large developers and bring them back into public ownership, complete the projects and switch to building for rent. The government should end debt payments to foreign investors and only meet obligations to small investors; and transfer housing out of the mortgage and private finance system.

Problems caused by the large private real estate sector

The real estate sector has got so large in China as a share of investment and output that it has seriously degraded overall growth. This is where the economy does need rebalancing. Outgoing PM Li said that China needed to “expand market access” for foreign investors, ‘prop up’ consumption and control risk in the real estate sector. Li pledged to help “high-quality, leading real estate enterprises” while continuing to “prevent unregulated expansion”.

Really, can Li square the circle? China’s private sector has mushroomed in the last two decades. It has led to an unhealthy expansion of billionaires and rising inequality of wealth and incomes. And just as in the West, as the profitability of productive capital fell, the capitalist sector switched into unproductive investment areas, like finance and real estate. Debt has rocketed. This has increased the risk of economic crises as in the West.

Contrary to the views of the Western experts and Li, it’s not less investment and more consumption; not less public and more private investment that China needs to sustain its previous economic success, but the opposite.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.