By Harry Hutchinson, member of Labour Party, Northern Ireland

The signing of the Good Friday Agreement twenty-five years ago promised to bring new political and economic prospects to Northern Ireland. As forecast by socialists at the time, however, the Agreement has done nothing to stabilise this conflict zone, move the region forward from being one of the most economically and socially disadvantaged in Europe.

The period of the Troubles, from the late 60s up to the time of the Agreement claimed the lives of almost 4,000 people, mostly civilians, but including security force personnel and paramilitaries, both Republican and Loyalist. Infiltration of Republican paramilitaries in particular, by MI5, continually undermined the so-called ‘armed struggle’, but failed to bring it to an end. Support for the IRA was continually waning and a war weariness was being felt, even in hard line Republican areas.

The 1990s brought about changes as working class people began to mobilise against both paramilitary and state violence. In 1992, a rally organised by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, largely through pressure from socialists, led to one of the biggest protests in Belfast against all the violence. This workers’ movement changed the political objective situation, further isolating the paramilitaries from working class people, and opened the way for an end to the troubles and at least the possibility of a new era.

Although the agreement was years in the making, finally on April 1998, a multi-party agreement was reached, essentially by Sinn Fein and the Ulster Unionist Party, then led by David Trimble. The agreement involved the establishment of a ‘power-sharing’ Assembly with an ‘Executive’ to run Northern Irish affairs. There were also intergovernmental bodies established to deal with affairs that related to Britain and the Irish Republic. The Agreement also allowed Northern Irish access to the European Court of Human Rights.

Constitutional arrangements to decided by a poll

The Good Friday Agreement recognised that Northern Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom for as long as a majority of the population in the North wished. In the event of a majority in the island of Ireland wishing to bring about a united Ireland, then the British and Irish Governments would work towards this consensus, but the constitutional arrangements would only be decided by a ‘border poll’ at some unspecified time in the future.

The Agreement that was reached with paramilitaries was for decommissioning of all weapons – so they were ‘beyond use – and for prisoners to be considered for early release, on the basis they did not reoffend. British troops were to be withdrawn, designated police stations closed, and the police of Northern Ireland was to be reorganised.

Referenda held in the North and in the South.

Referenda were held on the Agreement, both north and south of the border. Over 71% of the people of the North voted for the Agreement and over 94% in the South. In the North, almost all Catholics voted in favour, because they felt that the Agreement would give the ‘Nationalist’ community an equal say in the affairs.

The essence of the agreement was that it brought ‘in from the cold’, both Sinn Fein and the DUP, with their military wings. Both of these parties would come to dominate the new Assembly and, at first, they collaborated in what became a coalition.

Across Northern Ireland as a whole, the Agreement was overwhelmingly supported because it meant that an era of violent troubles would come to an end. There as also an expectation that there would be a ‘peace dividend’, of increased investment into new projects, meaning more jobs, and promising a prosperous future for the decades ahead.

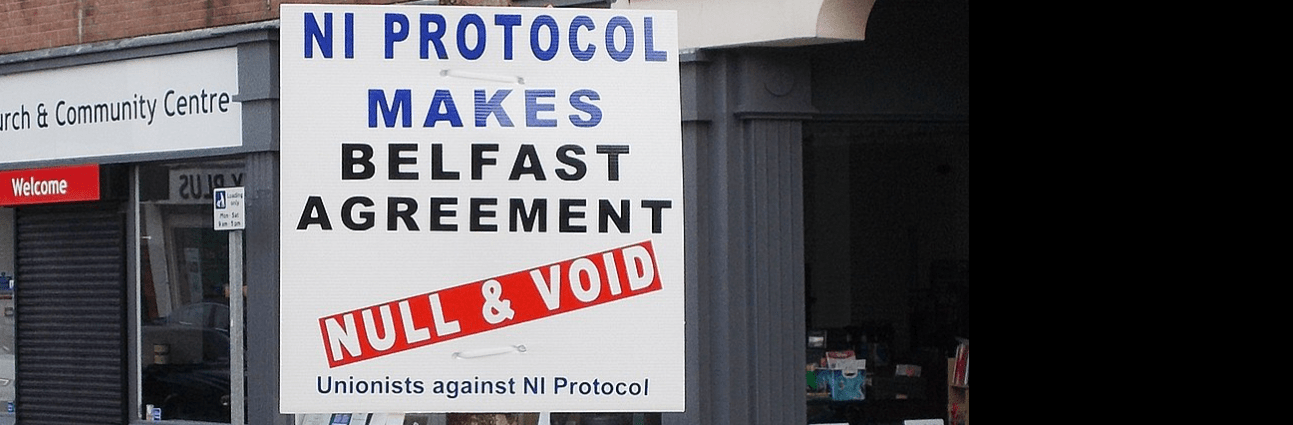

Socialists at the time, like all workers, broadly welcomed an end to the daily round of violence but pointed out that the Agreement in reality institutionalised sectarianism. The two main parties upheld the capitalist system and were united in support of corporate interests but each of them rested on sectarian base of support, which they were resolutely determined to maintain. Sinn Fein has continued to exploit the Nationalist question, which has been the dominant political factor in Ireland since Partition, and the DUP, especially since Brexit, have exploited the ‘weakening’ of ties with the rest of the UK. [Picture top from the NI port of Larne]

Both the main parties have collapsed the Assembly at some time

As a result of playing on the sectarian divisions, both Sinn Fein (SF) and the unionist parties have at various times collapsed the Assembly – which requires both ‘communities’ to function – most recently the DUP. They both play up to ugly sectarian divisions to protect their party positions.

In 2002, the Ulster Unionist Party (then the main Unionist Party) pulled out of Stormont after prominent SF members were exposed gathering intelligence through MI5 infiltration. In 2017, SF did likewise, as it was evident that its grass roots support was waning, from their support for health and public sector cuts. By raising the issue of the Irish Language Act SF was able to recover its political position. It was notably not health, housing, jobs, living standards or any other issue that might attract cross community support – but for SF it always has to be a national issue, one that appeals only to one half of the sectarian divide, its own base.

Today Stormont again remains in stalemate. This time, the DUP, has refused to take part in the Assembly because of the Northern Ireland protocols that, they say, weakens the NI link with the rest of the UK. They have been effectively exposed by Brexit but they are not slow in putting corporate interests first, this after the DUP former first minister had been forced to resign in the so-called ‘cash for ash’ scandal. This represented a fraudulent misuse of public funds, one of the biggest scandals in UK history.

On each occasion that the Assembly has been collapsed, both SF and the DUP have sought to reestablish themselves by upping the antics of nationalism or unionism above any interest they might pretend to have about the awful austerity facing the majority of the population of the North – an austerity that comes entirely from the Westminster government.

The promise of a ‘peace dividend was a fiction

The promise of a ‘peace dividend’ was always no more than a fiction, used to sell the Good Friday Agreement to workers North and South. Northern Ireland today remains by far the poorest region of the United Kingdom. It has a higher dependency on welfare, partly due to the consequence of the troubles, particularly mental illness. By any measure of economic well-being: housing, jobs, education, the state of the NHS and local authority services, life in Northern Ireland is worse than elsewhere in the UK.

In 2014 SF and the DUP implemented welfare reforms in the Stormont House Agreement. These reforms slashed incapacity benefit by between £2,000 and £3,000 annually for claimants. So as not to be blamed for the reforms, these parties handed control of benefits in Northern Ireland to the Tories in Westminster. Later in so-called ‘Fresh Start’ the two parties agreed to slash 7,000 public sector jobs, equivalent in population terms, to over a quarter of million in Britain. Skilfully, the main nationalist and unionist parties, by basing themselves on continued sectarian division, have introduced severe cuts and have at the same time been implicated privatising in public services.

A quarter of children in NI live in poverty. Wages, both in the public and private sector, lag 16% and 9% respectively, behind the rest of the UK. One in six of the population are on waiting lists for a consultant referral in the NHS. NI has the highest suicide rate in Europe as drug abuse is endemic. Most of the illicit drug trade is under the control of paramilitaries, which have morphed into well-armed drugs gangs.

Working people have cut through sectarian divisions

If there is to be any major change in Northern Ireland, it has been brought about by working people cutting through the sectarian divisions that exist and by uniting in defence of living standards and all those things that matter to workers’ families. The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s ended Unionist gerrymandering and brought about one-person-one-vote, along with an end to open discrimination in housing and jobs. It was workers uniting in the 1990s, that brought an end to paramilitary and state killings.

In 2016, a small socialist party, People Before Profit, rocked the political establishment. Their leader, Gerry Carrol, in the Sinn Fein heartland of West Belfast received got the second-highest vote in the regional election. Only the then First Minister, Arlene Forster, received a higher vote. The two PBP candidates collectively got 14,000 votes.

Jeremy Corbyn’s elevation to the leadership of the Labour Party also transformed the Labour Party NI into the largest membership Party in the North. But with the Labour Party refusing to stand candidates in elections in the North, this transformation was never tested in an election and the purge against members, initiated by the right wing after Starmer’s election, has gradually reduced Labour Northern Ireland to insignificance today.

A socialist agenda

Socialist have always maintained that the sectarian pro-capitalist parties in Northern Ireland, chiefly Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party, can solve neither the National question or the profound social and economic problems that exist.

Yet Northern Ireland has a strong trade union movement, and it is here, on the shop floor, in offices, factories and in workplaces, that workers of both communities mix and freely and mutually support to one another. This could be the basis of a new political non-sectarian movement that offered a struggle, for an improvement lives of all workers of all communities. But unfortunately, most trade union leaders have not realised the potential that exists in the trade union movement and have continually failed to take on the establishment.

Northern Ireland once again is facing a dangerous time. Violence is once again on the increase and some disaffected youth – those who have not experienced the Troubles or have yet experienced any ‘peace dividend’ are looking for a way to vent their anger, some by associating with paramilitary organisations and attacks on the police.

Today, the Good Friday Agreement that was welcomed by the big majority of the population has now lost much of the confidence of those same people. Hopefully, working class people will look for alternatives other than the main sectarian pro-capitalist parties. Workers have from time to time in the past shown a determination to unite against the sectarian the main Northern Ireland parties. Such opportunities will arise again.