By Sam Gleaden – health worker

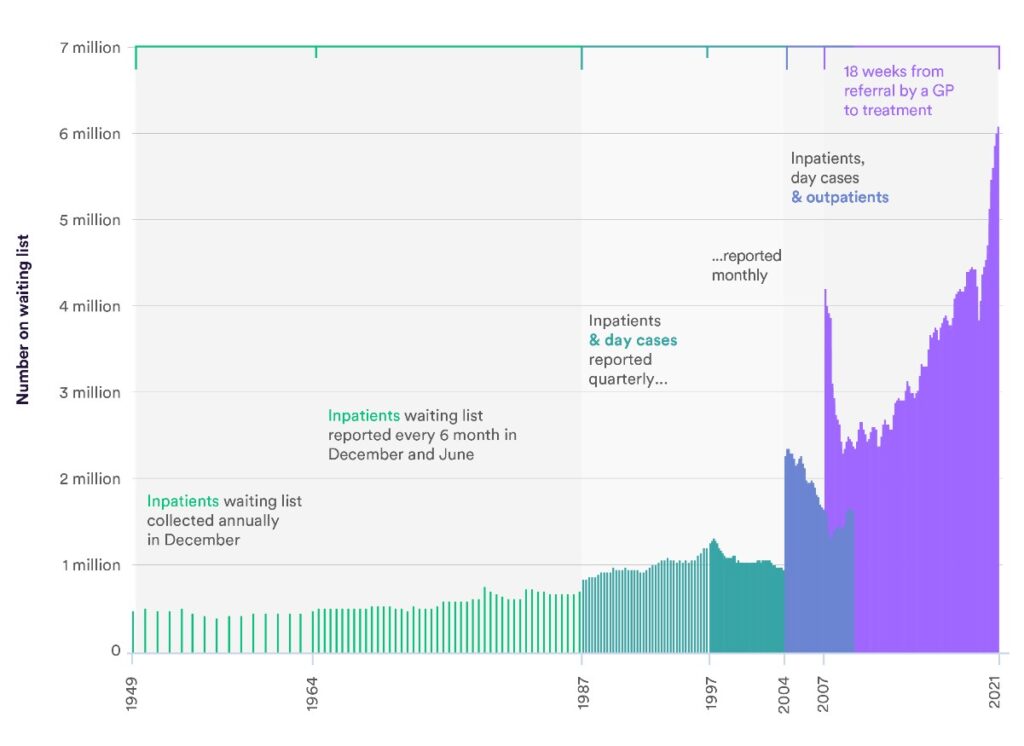

The NHS crisis has reached truly unprecedented levels, 7.21 million people are waiting for treatment, with 231 times the number of people waiting over a year for treatment compared to January 2020. We have heard horror stories of ambulances being unable to attend to the dying, with a record number of hospital trusts declaring critical incidents in 2022.

Unbearable conditions, on top of dramatically falling real wages, have led to an extreme staff retention crisis. September 2022 saw a record average of 9.7% unfilled positions across the NHS, a figure almost double that of March 2021. Poor mental health, caused by staff burnout, is overwhelmingly the greatest reason for leaving.

Although these terrifying figures have been blamed squarely on Covid, there are clear long-term issues stemming from a chronic lack of investment and corrosive privatisation.

A very brief history of NHS Privatisation

The NHS was originally organised with hospitals under direct government control, with GPs, pharmacists and local government playing a role in different services while staff ran hospitals through consensus management.

By the late 70s, the Conservatives were becoming frustrated with what they deemed to be poor management. Thatcher commissioned Sir Roy Griffiths to review the NHS, his ideas laid down the plans for creating a more ‘efficient,’ business-centric model within the NHS.

This culminated in the 1989 Working for Patients Act which created an artificial market in the NHS. This divided the service between commissioners with budgets, and competing public or private providers of services, with disastrous early consequences inearly outsourced cleaning facilities.

New Labour followed this ‘business knows best’ trajectory with the creation of independent hospital trusts, turning hospitals into a type of public corporation with individual budgets, the expansion of private sector funding for infrastructure and the implementation of the public sector’s new managerialism.

The most recent evolution is the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, which removed the health department’s direct responsibility for providing health care to the public, forced hospitals to become trusts and massively expanded the potential role of private services in hospitals’ income. This is part of a continuing pattern during the 2010s where budgets have been consistently cut and private sector involvement increased.

Problems of creeping privatisation

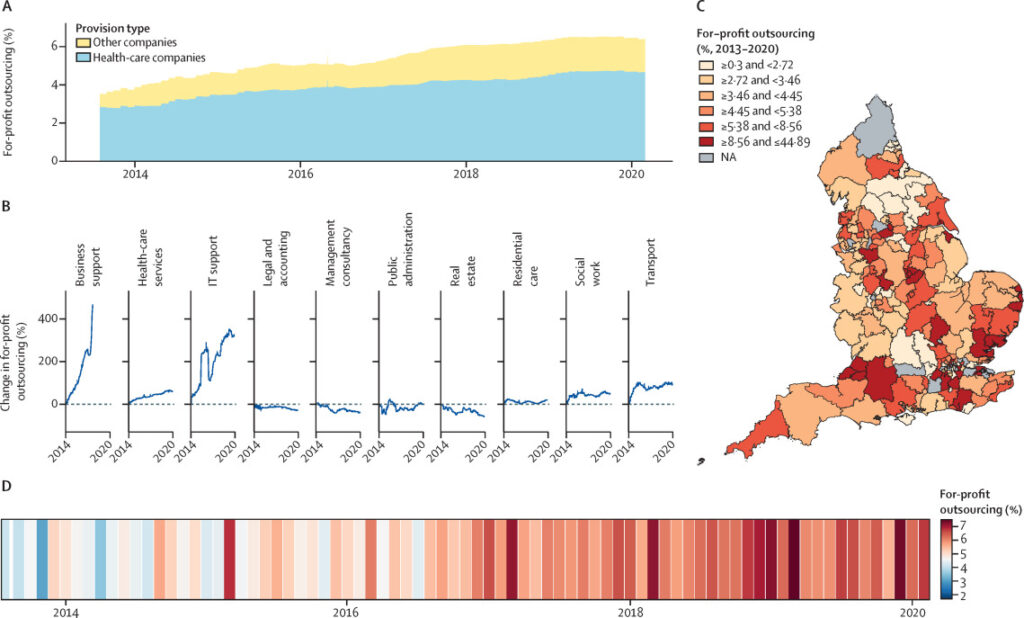

Increased outsourcing to the private sector has been disastrous. Less risky and more profitable parts of the NHS have been handed out to private companies. For example, up to 1/3 of hip joints are now completed by private providers. Between 2013 and 2019 an additional £5.6 billion was spent on private sector providers, an increase of 23%. Research from London School of Economics found that real government spending towards the private sector is now up to 25% of the health budget (significantly higher than the official government figure of 7%).

One recent Lancet study found clearly that increases in outsourcing were linked to higher mortality rates in the 2010s. Unsurprisingly, during the last 30 years we have seen a number of high-profile scandals due to outsourcing.

But outsourcing isn’t the only problem. Private Finance Initiatives (PFI), originally set up by John Major’s government and then massively expanded under New Labour, have left a large number of NHS trusts saddled with debts.

PFI is effectively an expensive mortgage that NHS trusts, and other public sector bodies, take out with a selection of companies (this helps to hide the debt from the government budget). These same companies then build and deliver the infrastructure itself, at great expense and at worse quality. In 2017 there were around 700 PFI schemes in Britain, with an estimated capital value of £59 bn but they will cost taxpayers over £308bn (twice the cost of the entire NHS each year).

As with PFI, the creation of the internal market has created needless inefficiencies in the name of profitability. Estimates for the costs of administrating the internal market range from an extra £4.5 bn a year (government official estimate) to up to£30bn a year, representing approximately 20% of the whole budget! Costs of the market stem from advertising, negotiating, contracting, auditing and monitoring contracts, all of which require a much larger bureaucracy.

Private Health Insurance

The erosion of the NHS relative to the needs of the population has seen a dramatic rise in the use of private insurance. The UK spends 2-3% less of GDP on healthcare than comparable nations and has subsequently far worse outcomes, such as one of the lowest bed-to-patient ratios in the developed world.

Unsurprisingly, private health insurance has grown faster in the UK than in any major economy. Up to 12% of people have now used the private sector for health care, as up to one third of us say that the NHS cannot meet our health needs. The growing sneaky privatisation in the UK is happening quickest outside the NHS, with the expansion of paid-for add-on services, such as quicker GP services. This sector has grown from £5bn to £35bn in the past 30 years, with insiders in private health expecting it to rise even more to £50bn by 2025.

All this amounts to the creation of a two-tier system where the best healthcare is given to those that can afford it, while the rest receive a budget health system geared towards private sector profiteering. This development is unsurprising given the backgrounds of those that have designed the long-term future of the NHS:-

“Our ambition should be to break down the barriers between private and public provision, in effect denationalising the provision of health care in Britain.” (Jeremy Hunt 2005, Direct Democracy: An Agenda For A New Model Party).

and Ex-Health Secretary

NHS Long-Term Plan – Integrated Care Systems

The latest development in the NHS is the ‘Long Term Plan’ (LTP). Set out by the Simon Stephens, the former head of NHS England (the body that now runs the NHS). It’s re-shaping the NHS on US care models with cost-cutting “efficiency” and greater involvement of the private sector at its core.

The latest phase of the LTP is in the creation of 44 new regional bodies, called Integrated Care System’s (ICS’s) which will control all NHS funding.

In the new ICS model NHS budgets will be decided under the direct influence of private companies – in official NHS England documentation, which tries to spin the changes as the greater ‘integration of our communities’. It ominously refers to “stronger partnerships in local places between the NHS, local government and others…” These “others” are the private companies, of course.

Developed at the 2012 World Economic Forum, and headed by project lead Simon Stephens, consultancy firm McKinsey& co-authors put forward two key documents which have heavily influenced the NHS Long Term Plan.

The focus of the reports was on how to create sustainable health care in a post-2008 world of high public debt and ageing populations.

High-cost, capital-intensive parts of the system like hospitals must be cut in favour of ‘patient-driven’ care (personalised budgets with costs put onto individuals), focused on preventative home-intervention healthcare, using greater digital technology. Additionally, cuts to staff will be made as new technology allows for the deskilling of the workforce. Much of this new technology for home-driven preventative care will be provided by 88 private sector providers already approved by NHS England.

ICSs will use risk planning techniques from the private health sector that focus on “value” driven models of care, meaning budgets will only be handed out on the basis of “efficient outcomes” rather than on the needs of the population. These budgets will be driven by the goals that maximise the opportunity for private sector involvement while saving public money.

In practice, this means cheaper staff, cutting bed numbers and selling off more health service assets in the name of “streamlining”. This will push more and more into the already growing private sector to meet their needs.

The Revolving Door

There is a tight relationship between leading members of NHS England, MPs and the corporate world of private health firms and outsourcing companies. The already mentioned Simon Stephens, former head of NHS England, was previously an executive at UnitedHealth, the largest health firm in the world.

Many Conservative MPs have links to private healthcare companies, including Andrew Lansley, the architect of the 2012 reforms, and the previous health secretary, and current chancellor, Jeremy Hunt. Many MPs often profit handsomely after leaving office by entering lucrative roles within the private healthcare sector.

New Labour are just as tied up in this culture, with former health Secretary Andrew Milburn and health minister Patricia Hewitt both working for private firms such as UnitedHealth and Bupa after their time in office. Simon Stephens was actually an advisor to Milburn during his initial stint in government, showing the dubious networks and copycat ideologies of the two parties.

The revolving door culture between the government, health and outsourcing firms led to disastrous policies during Covid. The handing out of crucial public health contracts to consultancy firms that have no specialism in healthcare led to the £22bn failure that was Serco’s track and trace system. This same process of outsourcing during covid has been miraculously regarded as a success by NHS England, and according to a recent advisory report to the government, has been given as a reason to expand private sector involvement in the NHS!

What comes next?

There is a clear long-term trend towards greater private sector involvement in the NHS. Fundamentally this is being driven by the needs of big business to find avenues of profit in a chronically stagnating economy. Leeching off the public sector through privatisation is a cornerstone of the neo-liberal ideology that has dominated society since the 1980s. This is why we see the prominent role of outsourcing firms in modern capitalism. The UK’s ruling class has become especially parasitic in such a decaying and dysfunctional economy.

The majority of the Labour Party is dominated by this same thinking. Keir Starmer’s recent comments about not “opening up the chequebook”’ and the “need [for] a strong private sector” in the NHS meaning no redistribution of wealth and further ‘efficiency’ through the use of the private sector.

There is plenty of evidence that many conservatives, NHS England executives and networks of healthcare/financial firms would like to destroy the NHS if they could. Whether this will lead to a full-blown US style private insurance model is a political question that will be decided by future struggles, both within the ruling class and its battles against the organised working class.

This is why Bevan famously said that the NHS will remain as long as there are people there to fight for it – understanding from its inception that it was a concession won from big business.

To save the NHS we must look to the strength of the labour movement. The current strike wave will be an incredibly important building block to redeveloping the organisation needed to resist further privatisation and cuts.

Whether we have a labour government or not, we will need to develop a party based on the labour movement and wider struggles – one which will fight for the principles of the NHS: full nationalisation under the democratic control of the public and health workers, rather than the open corruption of talentless bureaucrats and their outsourced healthcare cronies.