By Michael Roberts

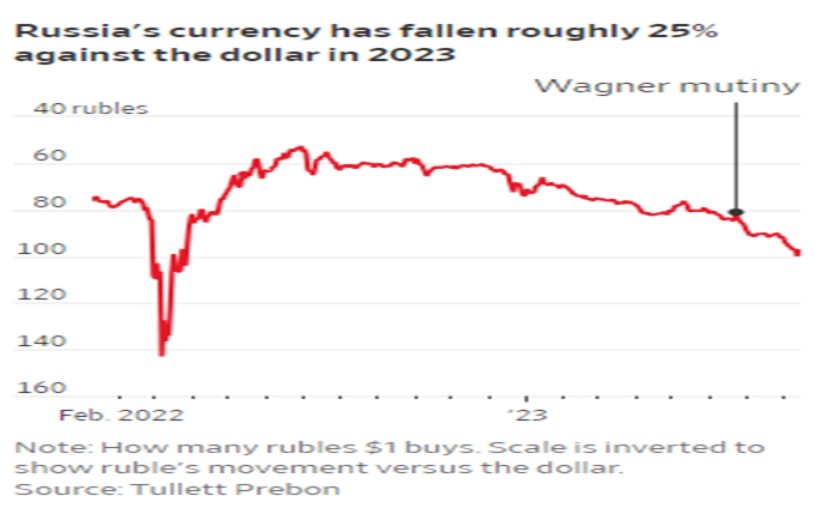

This week Russia’s central bank held an extraordinary meeting to discuss the level of its key interest rate after the Russian ruble fell to its weakest point in almost 17 months. The meeting decided to hike the bank’s interest rate for borrowing to 12% (up from 8.5%) in order to support the ruble.

The currency has been steadily losing value since the beginning of the year and has now slid past RUB100/$. That’s down 26%. The main cause of this decline is the fall in oil export revenues and the rising cost of military spending to prosecute the war against Ukraine.

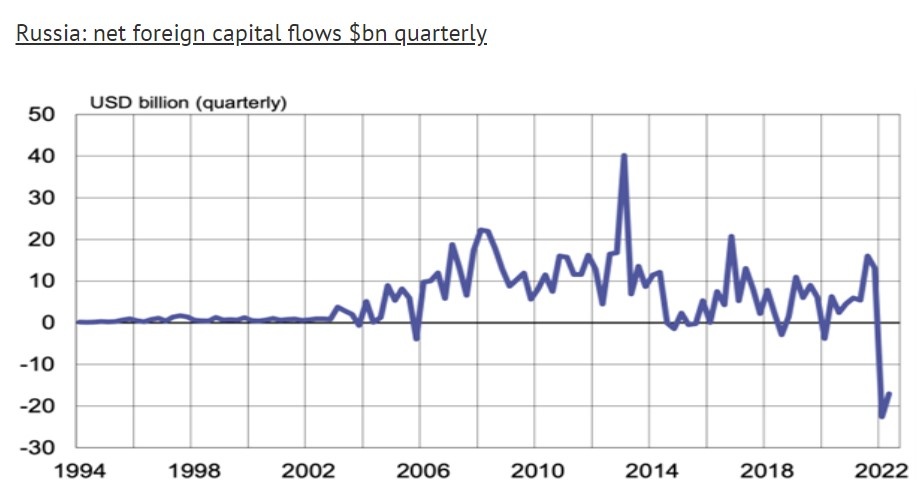

When the Russian invasion began in February 2022, the ruble dropped to a record low of RUB150/$. Rich Russians took their money out to the tune of $170bn, most of which ended up in Europe’s property and banks.

Weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, a US official predicted that sanctions would cut Russia’s GDP in half. But that proved nonsense. It fell just 2.5%. That’s because the central bank introduced capital controls that stopped the flow of money from rich Russians out of the country. And as the price of energy rocketed over the next year, the ruble gained strength and reached a seven year high.

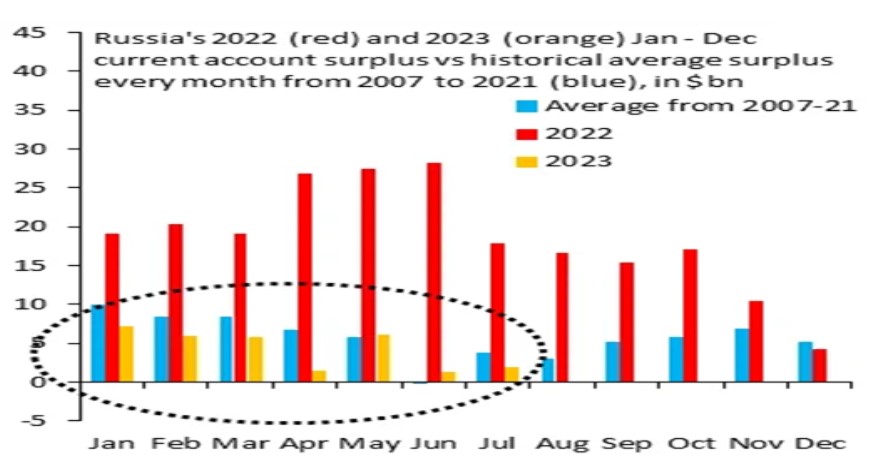

Export revenues rose, while the sanctions and falling domestic demand led to a drop in imports, so Russia’s trade balance and current account rose sharply, bolstering the ruble. Two-thirds of the trade surplus was due to rising export revenues and one-third due to falling imports.

It seemed that sanctions on Russian banks and companies and a ban on using Russian energy had failed to bring the Russian economy to its knees. Russia was able to reroute its energy exports into Asia (if at a lower price) and find ’shadow’ shipping to deliver it.

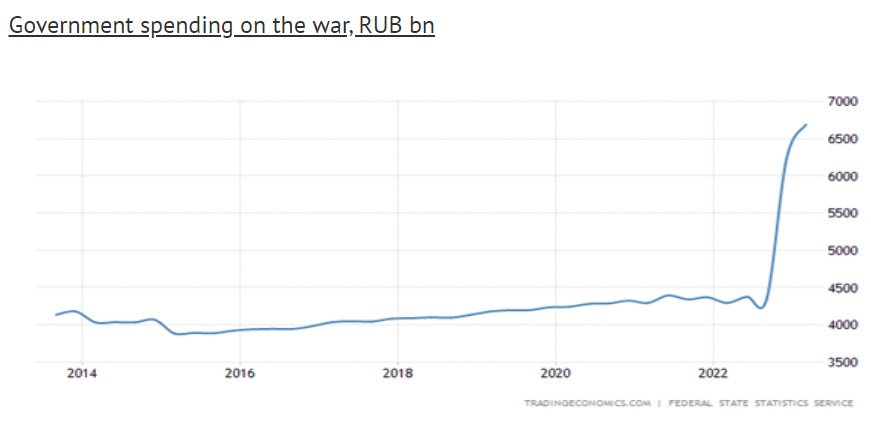

But energy prices have slipped back in the last six months and the price cap on Russian oil imposed and enforced by the NATO allies has had some effect in reducing export revenues, while the costs of the war have increased. The 2023 defence budget is planned at $100bn, or one-third of all public spending.

Russia’s national output rose 4.9% in the second quarter of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022. That sounds good, but much of the rise in output has been in the production of military equipment and services. The output of “finished metal goods” ie weapons and ammunition, rose by 30% in the first half of the year compared with last. Production of computers, electronic and optical products also rose by 30%, while the output of special clothing has jumped by 76%.

By contrast, auto output is down over 10% year-over-year. Russia is now a war economy. Russia has been able to import many of the goods that the West has banned—from iPhones to cars to computer chips—but it does so via third countries, a roundabout way that increases prices.

Immediately after the start of the invasion real wages for the average Russian fell sharply as the domestic economy dived. But energy revenues came through and low domestic demand kept price inflation low. As Russia workers were more and more employed in arms production or in the army, wages rose. In May 2023, real wages were up 13.3% year-on-year. Such an improvement no doubt helps keep support for the Putin regime.

But in recent months the energy revenue bonanza has fallen back. Russia’s energy export revenues are expected to decline from $340 billion in 2022 to $200 billion this year and next. Russia’s current-account surplus shrank to $25.2 billion in the first seven months of the year, an 85% fall compared with the same period last year.

At the start of the war, Russia had a large stock of financial assets ‘for a rainy day’. But it is now raining, if only as a drizzle. Russia’s National Wealth Fund (NWF) had savings and assets worth 10.2% of GDP at the beginning of the invasion. But that is now down to 7.2% as rubles lose value and war spending rises.

And the domestic civil economy and production is suffering. Sanctions are blocking technology imports and other key manufacturing parts. Some 65% of industrial enterprises in Russia are dependent on imported equipment.

But the impact of sanctions is slow burn. It may weaken Russian productivity and domestic production over the long term, but it is not going to stop the Russian war machine now and energy revenues to finance it. That could only happen if fast-growing Asia led by China and India refused to buy Russian oil and gas, but the opposite is the case – they are buying more at cheap prices.

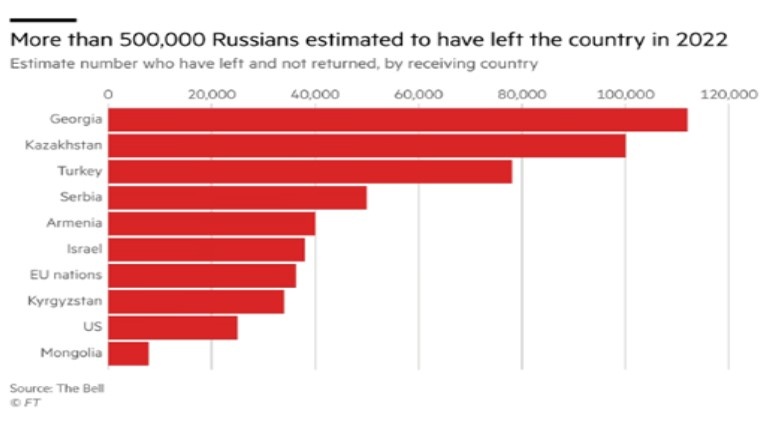

Russia’s war machine will continue but as emigration of skilled workers and capital owned by richer Russians accelerates, it is weakening the currency and reducing available skilled labour in production.

Inflation had fallen in the last year due to the collapse in domestic demand and imported goods. But if the currency continues to dive, then it will start to rise, increasing the pressure on the central bank to raise interest rates to support the currency and try to curb inflation. A stronger ruble and higher interest rates would mean lower foreign currency revenues and a weaker domestic economy. That will hit Russian households hard.

As it is, potential average growth is probably no more than 1.5% per year as Russian growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population, with low investment and productivity rates. The profitability of Russian productive capital even before the war was very low.

The economics suggest that Putin can continue the war against Ukraine for several years to come, even taking into account the collapse in the currency and rising inflation and interest rates. Of course, that does not take into account political developments (like the Wagner revolt or gains by Ukraine’s NATO backed army). They could threaten Putin’s rule. And there are presidential elections in Russia next March – as supposedly there are in Ukraine. Both Putin and Zelensky must face the voters – at least theoretically.

But the underlying message is that the weakness of investment, productivity and profitability of Russian capital, even excluding sanctions, means that Russia will remain feeble economically for the rest of this decade.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.