Andy Ford writes the latest in his occasional series on WW2 in the Soviet Union.

Eighty years ago, the Battle of Kursk sealed the doom of the Nazi regime. After Kursk, the Nazis would never again be able to mount any sort of strategic attack or offensive on the Eastern Front. From then on, it was a retreat, all the way back to Berlin.

Following Stalingrad, the two sides were in a state of balance. The Russians had rebuilt the Red Army back from the near destruction of 1941 and had learnt a lot of lessons the hard way. Their strength was constantly increasing as the huge factories beyond the Urals churned out thousands of tanks and other weapons. The Red Army officer corps was now based on merit, not abject dependence on Stalin, and a number of talented generals had emerged.

On the other side, the Germans were now stretched and worn out, running low on manpower and short of key raw materials. At Stalingrad they had lost the equivalent of 6 months production of the entire German economy. But they were still 1,000 miles within the borders of the Soviet Union, skilled in defence and brutal in occupation.

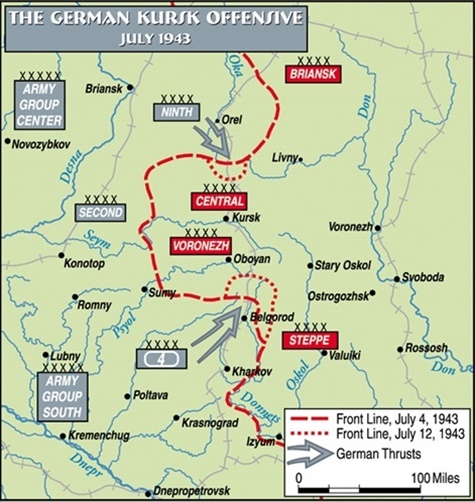

The rapid advance of Soviet troops after Stalingrad was checked, and partly reversed, by General von Manstein at Kharkov in February 1943 and the frontline was left with an enormous bulge or salient into German held territory, in and around the ancient Russian city of Kursk. It was an obvious place for a German attack, in fact, in some ways, too obvious.

German debate

For the Germans, as they evaluated their situation post-Stalingrad, it was clear they could no longer win the war in the east. The best they could do would be to force the Soviet Union to a separate peace. Hitler had always believed that in the long, or even the medium, term, the ‘unnatural alliance’ between the Soviets and the USA and Britain could fall apart at any time. So the idea was to ‘bleed the Russians white’ by making them take such casualties, and lose so many prisoners, that they would be physically unable to continue.

But then a disagreement blew up between Hitler and his generals. The generals, led by the most talented, von Manstein, argued for a ‘backhand blow’, where they would let the Red Army attack and then encircle and annihilate them. Manstein had just done exactly that in the 3rd Battle of Kharkov, where he allowed the Red Army to dash towards the Dnieper, only to trap and surround them. The Russians had lost 42,500 killed or missing in that battle compared to German losses of just 4,500.

But Hitler needed a victory to keep his wavering allies – Italy, Finland, Romania and Hungary – onside. In particular, he worried about a possible Italian capitulation after the destruction of the Italian 8th Army at Stalingrad, followed by the surrender in North Africa in May 1943. So he gambled on the superiority of German tactics and training, their record of victories in summer, and the Nazis’ new ‘wonder weapons’, the Panther and Tiger tanks, and the Ferdinand tank destroyer (designed by Porsche – ,no less). The decision to attack was taken on April 15th, and the obvious place was Kursk, with its relatively flat terrain making it the ideal place to try out these new tanks. The aim was to encircle Kursk, and force the surrender of the Soviet forces there.

Russian preparations

The Russians also debated an offensive versus defensive strategy for the summer of 1943. Stalin, as usual, wanted an all-out attack, but the generals, led by Zhukov, counselled defence, followed by a counter offensive. In this case Stalin actually listened to his military specialists and the decision was for defence in depth. Russian intelligence began to pick up on a build-up around the Kursk salient, and this was followed by a report from ‘Agent Lucy’ who was passing the details of German High Command decisions to Moscow almost as soon as they were made. Further confirmation came from the British Enigma code breakers at Bletchley Park.

The whole area around Kursk was transformed into one huge defensive complex with fortifications, tank traps, mine fields and prepared anti-tank firing zones. In May 100,000 civilians were at work on construction, rising to 300,000 by June. 20,000 artillery pieces, 5,000 anti-tank guns and 920 Katyusha rocket batteries were deployed in eight defensive belts with a total depth of up to 30 miles, with a whole army in reserve. As news of Russian preparations leaked back to the Germans, Hitler himself said that the thought of the battle “turns my stomach” and in his message to the massed Nazi soldiers he told them, “This day you are to take part in an offensive of such importance that the whole future of the war may depend on its outcome”.

The German attack

Alexander Werth, in his book “Russia in the War” well describes the tension in Moscow in June and July, as the Soviet people waited for the anticipated onslaught. Hundreds of thousands of Nazi soldiers, armed with the best technology the Reich could supply, stood ready to attack in a “war of extermination”. The Stalinist ‘Red Star’ paper tried to rally morale in very nationalistic terms:

“Our fathers and our forebears made every sacrifice to save their Russia, their homeland. Our people will never forget Minin and Pozharsky, Suvorov and Kutuzov, and the Russian Partisans of 1812. We are proud to think that the blood of our glorious ancestors is flowing in our veins, and we shall be worthy of them.”

The attack began on 5th July. The northern Nazi pincer, attacking from Orel, ran into minefields, prepared machine gun fire zones and strong resistance of the Russian infantry in their trenches. The Germans advanced, but only with huge losses. Using the Tiger tanks, they did succeed in taking a few villages, but 100 other armoured vehicles were immobilised by mines. The strength and depth of Soviet defences came as a revelation to the Germans. The next day the offensive continued, with the Germans committing hundreds of tanks in an assault on Olkhovatka, on the hills behind the villages. It was one of the Russian strong points, and many of Nazi tanks were picked off in the Soviet anti-tank fire zones.

By the evening of the 6th July, the Tiger battalions were shattered. General Model committed his last reserves of armour to try and break through but all they did was add to the piles of wrecked German tanks strewn round the battlefield. By July 12th there was nothing left and Model ordered his troops over to the defensive. He had lost 400 tanks and 50,000 men to penetrate no more than 10 miles into the Soviet lines.

The southern pincer, attacking from Kharkov and Belgorod, initially had more success. German sappers cleared paths through the minefields and at 4 am on the 5th July, 700 tanks and assault guns pushed though the Soviet defences on a 30-mile front. Three elite Waffen SS divisions seized a number of heavily fortified villages on the route towards Kursk, but once the initial gains were made, the innumerable anti-tank defences, minefields and barbed wire slowed the advance.

However, the next day, re-armed and re-fuelled, the SS formations took the strategic village of Luchki, opening up a gap in the second Soviet line of defence. It was a serious situation for the Russians and the 5th Tank Guards army was readied from the Soviet reserve. On the 7th July 400 German tanks attacked and forced a Soviet retreat back to the River Psyol. On the 8th the Germans resumed, led by the elite SS ‘Grossdeutschland’ division leading to a huge battle around the Soviet second line of defence.

A battle beyond all imagination

A German account says, “A ferocious tank battle ensued on the steppe, on hills, in gorges, ravines and in settlement. The scope of the battle was beyond all imagination. Hundreds of panzers, field guns and planes were turned into heaps of scrap metal. The sun could barely be seen through the haze…”

A Russian officer described the scene from his point of view: “Towards evening of 8th July our regiment had just 10 tanks left. Our regiment was no longer able to hold its sector…One would think we were on an island in the midst of a sea of fire. We had to retreat to find our battalion”. By late evening the Germans were indeed threatening to break through, but the cost had been huge – 230 tanks and 11,000 men killed. The Germans now decided to refocus their attack on the town of Prokhorovka, which would, if captured, pierce the last line of Soviet defence and allow the Germans to attempt the encirclement of the Soviet forces in the Kursk salient. On the 11th July a huge force of 600 tanks was thrown against Prokhorovka on a six-mile front – a density of 160 tanks per mile of the front. Such was their initial success that the Soviets had to call up whatever armoured forces lay to hand to block the expected attack on the 12th.

At dawn, an initial mass of 200 German tanks moved forward, to be met with a Soviet artillery barrage, under cover of which the 500 tanks of the Soviet reserve rushed forward out of the woods, where they had lain camouflaged, and engaged the Nazi force. Because of the Tiger tank’s superior armour the Russians had to get close and amongst the German tanks to fire at their vulnerable side armour. A huge tank battle, the biggest in history, developed, as the tanks blasted at each other at point blank rage, while overhead, Soviet and Nazi planes fought each other and bombed and strafed their enemies on the ground. Finally, the Russians deployed their 5th Guards Tank Army and the SS panzer divisions were brought to a halt just outside Prokhorovka. The Nazis had been stopped, but at a cost of 250,000 Soviet soldiers killed, captured or missing and around 6,000 tanks and assault guns destroyed or damaged beyond repair.

War of two social systems

Trotsky had written that in the event of war between Nazi Germany it would be not just a case of war between two countries, but between two social systems. The contest between the German Tiger and the Soviet T-34 tanks did show this.

The Tiger tank was hand built and no more than 1400 were ever made, as it was so expensive. Once on the battlefield, it was indeed a killer – at Kursk the losses of Russian tanks were about 7 or 8 for each Tiger – but it was notoriously unreliable, so much so that many of them never made it that far. The transmission wore out at around 100 miles due to the huge weight of armour it was carrying and the weight also meant it was prone to fall into collapsed cellars and culverts, or through any but the strongest bridges. Once it was stuck, its 57 tons made it very difficult to retrieve. For this reason the Tiger tank commanders often cycled along in front of the tank to look for dangers and obstacles as it drove to the assembly point for an attack.

By contrast the T-34 tank was mass produced in huge numbers – about 85,000 in the course of the war. It had broad tracks for Russian terrain, it had sloped armour, so that, until Kursk, the German shells just deflected off, and it had a reliable engine. But above all, it was cheap. Like a lot of Soviet technology, it was robust, maybe primitive, but ‘good enough’. Once the elite SS Panzers had been fought to a standstill at Kursk, the Soviet high command, the STAVKA, was able to use hundreds of T-34s to unleash major offensives north and south of Kursk. The planned economy proved itself, not in theory, but in the heat of war.

Nazis driven back and almost encircled

The Russian counter-offensive north of Kursk was targeted on Orel, where just two years before, the Nazis had arrived to find the “trams still running”. The Russian attack threatened to cut off the forces assembled for the northern Nazi pincer at Kursk and they were forced into a chaotic retreat back into Byelorussia. The encirclers threatened to become the encircled.

In the south, the Red Army attacked and liberated Belgorod and then drove on finally to free Kharkov from Nazi occupation. By 23rd August 1943 they had pushed the Germans back by between 25 and 75 miles, leaving them in a position to end the Nazi occupation of Ukraine. But the cost had been horrific. The Soviet general, Rotmistrov, observed, “More than 700 tanks were put out of action on both sides in the battle. Dead bodies, destroyed tanks, crushed guns and shell craters dotted the battlefield. Not a single blade of grass was to be seen; only burnt, black and smouldering earth throughout the depth of our attack – up to eight miles”

Alexander Werth travelled to the area a few weeks after the liberation and described the scene: “ I could see how the area to the north of Belgorod, where the Germans had penetrated some thirty miles into the Kursk salient, had been turned into a hideous desert, in which every tree and bush had been smashed by shell-fire. Hundreds of burned-out tanks and wrecked planes were still littering the battlefield, and even several miles away from it, the air was filled with the stench of thousands of only half-buried Russian and German corpses”.

Orel under German occupation

Werth also interviewed survivors of the Nazi occupation of Orel. In Orel, a city of 114,000 pre-war inhabitants, only 30,000 remained. Werth estimated that 12,000 had been murdered or starved, and 12,000 deported to forced labour, while unknown thousands had fled into the forests to join the partisans. Many had been publicly hanged in the town square. The Germans had appointed a Russian collaborator as mayor and had even imported some émigré landowners – but then had not restored their property, as they needed to exploit the food production of the area for themselves. In the winter of 1941, hundreds died of starvation, particularly the old, the sick and the young. Their bodies just lay in the streets. In the spring of 1942 people began to get seven ounces of bread a day – if they worked for the Germans.

The civilians described the fate of Russian POWs – up to Stalingrad they had been starved and “allowed to die like flies”, with 30 or 40 deaths a day; after Stalingrad they were preserved for forced labour or pressured to join the Germans as auxiliaries. The Germans had re-opened the churches, under a stooge bishop based in Berlin, but despite their intentions the churches became centres of discussion, resistance and aid to the Russian POWs. The schools were placed under the control of a Russian émigré who redesigned the curriculum to emphasis the racial inferiority of the Russian people and their culture. Not surprisingly, the Red Army were welcomed with absolute joy when they finally liberated the city on August 4th.

After effects of the battle

The Germans could never again mount an offensive in the east. They set up line after line of defence and were repeatedly forced out of them. In reality the war was lost for them, and everything that happened subsequently was a tragic waste of life and resources. Kursk has been described as a German tactical victory – as they inflicted far heavier losses on the Red Army than they themselves sustained – but a strategic defeat. They were stopped, but only by the heroism of Soviet military formations like the 5th Guards Tank Army, who lost 50% of their men and machines in the course of the battle.

The ultimate end of the Nazi regime was now assured.