By Roger Silverman

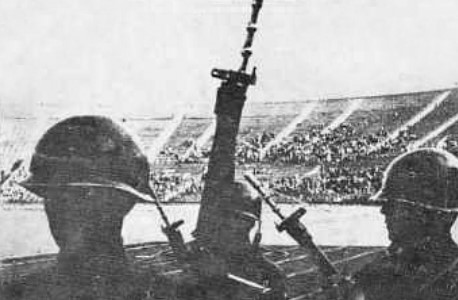

[Editorial note: Fifty years ago this month, on September 11, 1973, a military coup took place in Chile, putting a committee (‘junta’) of generals in power, led by General Pinochet. The coup resulted in the bombing of the presidential palace and the subsequent murder of the president, Salvador Allende. Allende’s government had been a left “Popular Unity” government, committed to reforms in the interests of workers and the overthrow was instigated by the Chilean and international capitalist class.

This article by Roger Silverman, was published in the Militant International Review in January 1974. It gives a powerful description not only of the events that led up to the coup itself, but also points to the lessons that socialists need to learn from it. Part ONE can be found here and Part THREE of the article will be published later]

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

Why the middle class despaired.

The so-called “parties of the middle class” have always been based on deceit of the middle class. For what are the real historic interests of the middle strata of society? The lower peasantry in the countryand the small businessmen in the town, squeezed dry by finance capital and crushed by the monopolies, face under capitalism only bankruptcy and ruin. They can only be forced down into the ranks of the proletariat. Their only real salvation, then, lies in the victory of the workers and Socialism. The parties which misrepresent them under capitalism are financed by their worst enemies – Big Business – in order to pander to their basest prejudices and rouse them against the workers. The presence of such parties in coalition with the workers’ parties can only bring a Trojan Horse of the ruling class into the alliance.

Every such coalition leads eventually to catastrophe. In Germany, the Menshevik policies of the Social-Democratic leaders following the 1918 revolution paved the way for terrible social crisis and the trampling of the workers under the jackboots of Hitler’s Gestapo. In Spain, the road of “Popular Frontism” led to the slaughter of a million people and the victory of Franco. In France, it led directly to the Vichy regime and Nazi occupation. In Greece, it led to the colonels’ putch. In Brazil and Uruguay, it had the same consequences.

The only reason why it did not end in a horrible defeat in Russia at the hands of General Kornilov – the Russian Franco or Pinochet – is that there was a Bolshevik Party which struggled tenaciously against the politics of class collaboration, and in mobilising the workers for socialism won all the millions of toiling people in town and country into a real alliance to change society. The Bolsheviks formed a coalition government with the left wing of the Social-Revolutionaries – the poor peasants whom they had won away from the treacherous double-dealing of the S-R leadership, and thus created a real unity of the working masses.

It is perfectly true that Allende did not have an overall majority of the population behind him, and that it was necessary to win over the mass of the middle class. But he demonstrated tragically that concessions to the Right were no way to do it.

Bold reforms carried out

The fact that Allende won 36.2% of the votes, more than either the National or the Christian-Democratic candidates, marked the beginning of the Chilean revolution. Only 20 years earlier, he had won a mere eight per cent of the votes! All the workers except the most highly-paid, and a large section of peasants, voted for what they saw as fundamentally revolutionary change. Allende began with far more support than the Bolsheviks had in February 1917! Bold propaganda, the formation of workers’ councils, mass action, could have quickly rallied wider strata agains the big landowners and the monopolies.

The bold reforms, which were carried out mostly within the first year or so of the “Popular Unity” government, did inspire enormous support. The nationalisation of the copper mines was supported by 93% of the population, and even the ultra-Right National Party had to vote for it in Congress. In the 1971 municipal elections, the “Popular Unity” candidates won no less than 49.7% of the votes – more than the British Labour Party has ever won in any general election!

What is more significant still is the fact that it was the Socialist Party on the left of the coalition which raised its share of the vote from 13.9% to 22.4%, while the Radicals, the main force of the right of the coalition, halved their vote from 16% to 8%. It was the radical action of the government, and not its concessions, which was winning support. Even in the “mid-term” Congressional elections of March 1973, which took place amid economic chaos and after the first crippling lorry-owners’ strike, the “Popular Unity” candidates still won 44% of the votes. Once again, the Socialists doubled their Congressional seats from 14 to 28, while the Christian Left suffered a decline from seven seats to one.

But why were large sections of the middle class discontented under Allende’s government? Not because it was “too left”, but because despite the massive extension of public ownership, overall control of the economy was still not in the hands of the government. For it was above all the chronic rate of inflation which drove sections of the middle class to the right. Inflation was caused initially by the penetration of millions of worthless paper dollars from the USA, into Chile as into the rest of Latin America and indeed the whole capitalist world.

It soared sharply iin the last period of Allende’s government, getting a new impetus partly from the deliberate campaign of sabotage by the capitalists of Chile and the USA, and partly also from the big wage and pensions increases which pumped extra currency into a chaotic capitalist economy. Only a planned economy, rationally harmonising the overall growth of production, could guarantee secure and rising living standards.

Inflation continually undermined government

At the end of June 1973, the cost-of-living index had risen by 283.4% in 12 months. In the first six months of 1973, food prices rose by 68.6% and clothes by 166.7%. Money supply was rising by nearly 1% a day! The economy because grotesquely distorted. A senior United Nations executive pointed out, for instance, that a bottle of Coca-Cola cost more than a ton of steel, and a plastic bag more than the cement it could hold! The nightmare of inflation continually undermined the government’s reforms. Wage increases disappeared before the ink was dry on the banknotes. To protect the workers’ living standards, the government had to grant bigger and bigger wage increases.

In January 1972 wages were raised by 22.1% and in October they were raised again by 99.8%. Even this was barely sufficient to catch up with prices. So it was decided to pay workers partly in kind rather than in cash. Naturally, in conditions of dire shortage, grossly exacerbated by the lorry-owners’ strike, a black market boomed everywhere, aggravating inflation still further. By the time of the coup, half the food consumed had been bought on the black market. The escudo, valued officially at 350 to the dollar, soared to unofficial exchange rates of over 2,000.

The workers were partly insulated against the effects of inflation, by the wage increases and the payment in kind. But the middle class were plunged into a nightmare of insecurity. They depended on cash, and their lives were rocked by instability. In the two weeks preceding the “employers’ strike” on November 1972, Argentine beef prices soared by 200%, and those of sugar, coffee, flour, milk, butter and margarine nearly doubled! It is not surprising that they were prey to the strident propaganda of the capitalist Press against the government.

The middle class are doomed under capitalism. They will see that even the Generals, with all their guns and their smart uniforms, cannot command prices to “stand at attention”. The only way out of the impassed of inflation lies in the construction of a publicly planned economy. If the Chilean workers’ parties had conducted a forthright campaign on this programme, and exposed the rackets and the profiteering of the monopolies, they could have won far bigger strata of the middle class. But to do this, they would have had to break with the “consensus” with the Radicals and the Christian Democrats.

Allende’s vacillation, temporising and half-measures drove the middle class to despair. The government faced a rising revolt of the shopkeepers, lorry-owners, doctors, small farmers, clerical workers, bank employees, lawyers, teachers, airline pilots, and the highly-paid copper miners, all of whom participated in crippling strikes. Middle class housewives took to the streets. It was out of the ranks of the middle strata that recruits were made for the small but ferocious gang of Fascist thugs, the ”Patria y Libertad”, which reared its head with growing audacity.

Allende imagined that parliamentary concessions to the Christian Democratic politicians would endear him to the middle class, regardless of the problems they faced in the real world outside Congress. Allende bargained with the Christian Democrats at every turn, even begging them in the last days before the coup to enter the Cabinet.

It was the Christian Democratic Party, in league with the Nationals, which brought down one Allende Cabinet after another, even impeaching certain Ministers. Finally, it voted with the Nationals in favour of the notorious censure motion, which accused Allende of “violating the Constitution” and in the next breath “reminded the armed forces of their duty to protect the Constitution” thus brazenly inviting the Generals to stage a coup.

Capitalist or Workers’ Democracy?

Allende’s first and most fatal concession came even before his election as President had been endorsed by Congress. He secured the votes of the Christian Democrats only on the basis of accepting a list of crucial demands including promises not to interfere with the “freedom of the Press” (ie the freedom of the Press tycoons to pour out a ceaseless daily flow of lies, filth and slander against his government), not to touch the judiciary, and – most deadly significant of all – not to tamper with the armed forces. He promised not to allow the formation of any “unconstitutional private militias”, to “appoint no military officers not educated in technical academies” and to make “no changes in the strength of the Army, Navy, Air Force or national police…except by laws passed by Congress.”

Since Chilean politicians have always boasted that Chile has “a Prussian Army, a British Nave and an American Air Force”, that was fatal! Why did the Christian Democrats insist on it, if not to keep open the option of a military coup later on? Unlike Allende, who still talked of “strengthening democracy”, the Christian Democratic leaders obviously had no illusions about the true essence of the State – the “armed bodies of men”. The State apparatus thus remained firmly in the hands of the ruling class.

What did this mean for the “Popular Unity” government which nominally presided over it? The Supreme Court, with increasing insolence, overruled its authority, upholding, in one monstrous example, the appeal of the putschist General Viaux, and substituting for the original 25-year sentence a mere two-year jail term – quite a lenient penalty for plotting to overthrow the elected government by force! Allende last June accused the Supreme Court in an Open Letter, of “partiality in the administration of justice”. And the armed forces, under the grip of the officer caste trained in the elite military academies, killed the President, dissolved Congress, suspended the Constitution and ruled by decree.

Coup postponed at first, at Washington’s request

Nobody could reasonably complain that the Generals had not given ample warning of their preparations for military intervention. Two days before Congress ratified Allende’s election, the Army Commander-in-Chief, General Schneider, was assassinated for opposing a coup. Then a coup was prepared by General Viaux, General Valenzuela and Admiral Barros – a coup postponed only at Washington’s request, as we have already seen. The secret correspondence on this conspiracy, including the clear warning of Washington’s support for a future coup, was published in 1971 and common knowledge to every Chilean. Countless beatings and assassinations were committed by the “Patria y Libertad”. In the countryside, a 2000-man force was recruited to sabotage transport, water, gas and power supplies.

The big landowners stock-piled machine guns. Only weeks before the junta seized power, there was a full-scale revolt by the Admirals and troops clashed outside the Presidential Palace. Allende’s own aide-de-camp was murdered. It was against this backcloth of violent tension that the “Comrade President” walked on to the stage, promising to “strengthen democracy” and ultimately “instal a new system in which the working class and the people are the ones who really exercise power.”

How was this to be implemented by a governmnt which had just assured the ruling class of unchallenged control of the armed forces, the judiciary, the Press and the civil service? Were the capitalists really expected to sit back and watch their power being dismantled, without any attempt at resistance?

Allende said on one occasion: “Chile has chosen to carry out a revolution within a bourgois democracy and will continue to do so, even though it is difficult.” What did he mean? Was it to remain a “bourgeois democracy” after the revolution had been accomplished? If not, how was it to be transformed? If so, in what did the “revolution” consist? Was it the “anti-oligarchic and anti-imperialist” revolution? But if the Chilean capitalists were supposed to be an ally in this fight, why should it be “difficult” to pursue it within a bourgois democracy?

No such thing as a ‘neutral’ , classless ‘democracy’

The truth is that Allende, like many others before him, supposed the State to be a neutral entity, which could be “democratised” and later put at the service of the workers. All the promises to “strengthen democracy” remained pathetic hopes. Allende, in the event, never dared to hold a plebiscite to consolidate his authority and clip the powers of reaction, although he was constitutionally entitled to do this. He never submitted his proposals for the replacement of the two Houses of Congress by a single, directly-elected unicameral “people’s parliament”. He even withdrew his proposal for local “neighbourhood courts” of lay trade unionists and peasants.

There has never been any such thing as a neutral, classless “democracy”, and Allende made strange claims for a leader of a “Marxist-Leninist” Party. As Lenin argued in The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, “If we are not to mock at common sense and history, it is obvious that we cannot speak of a ‘pure democracy’ as long as different classes exist; we can only speak of class democracy.” It is “bound to remain restricted, truncated, false and hypocritical, a paradise for the rich and a snare and a deception for the exploited, for the poor.”

“There is not a single state”, wrote Lenin, “however, democratic, which has no loopholes…in its constitution, guaranteetring the bourgeoisie the possibility of despatching troops against the workers…in case of a ‘violation of public order’, and actually in case the exploited class ‘violates’ its position of slavery and tries to behave in a non-slavish manner.” That was the nature of the “bourgeois democracy” in Chile, and recent events there demonstrate more eloquently than any theoretical arguments, the frailty of capitalist democracy when the ruling class feels its vital interests threatened.

Workers’ councils could have been set up

There is only one way to “strengthen democracy”; to take the power and wealth out of the hands of the capitalists, to establish workers’ management of the economy as a whole and workers’ control in the factories. Workers Councils must be set up in every locality, composed of lay delegates elected from all the workplaces and subject to instant recall. Every Council must elect delegates on the same basis, to a Regional and Central Workers’ Council, which would in turn report back to the local and regional Councils.

There must be no standing army or police force, but an armed people. No administrator must be paid more than the average skilled worker’s wage and all state duties should be rotated to involve the entire working population. That is the foundation for a workers’ democracy, as described by Marx, Engels and Lenin: a State which would gradually wither away and dissolve into society, so that “government of the people” would be replaced by “administration of things.”

The most consisten theoretical supporter of Allende’s programme was Luis Corvolan, General Secretary of the Chilean Communist Party – a Party, incidentally, which was on the Right of the coalition and vociferously defended every concession to the Christian Democrats. Corvolan argued again and again that, as he put it as late as in November 1972, “in the conditions prevailing in our country, changes cannot be effected according to the classical pattern of revolutions. They can be effected only within the frame of the law.”

Every scientific socialist since the days of Karl Marx has argued tirelessly that abstractions like “democracy” or “the law” are meaningless unless they are given class content. Corvolan meant that revolutionary changes could be brought about within the framework of capitalist law. Once again, the experience of all history and its concentrated expression in Marxist theory has long ago refuted this dream.

Marx and Engels concluded from the Paris Commune over a hundred years ago, that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes.” (Introduction to Communist Manifesto). Marx wrote that “the task of the revolution is no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to the other, but to smash it, and this is essential for every real people’s revolution.” (Letter to Kugelman).

Engels, again, spelt out the answer to Allende and Corvolan: “From the very outset, the Commune had to recognise that the working class, once in power, could not go on managing with the old state machinery; that in order not to lose again its only just won supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery used against itslef, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment.” (Introduction to Civil War in France).