By John Pickard

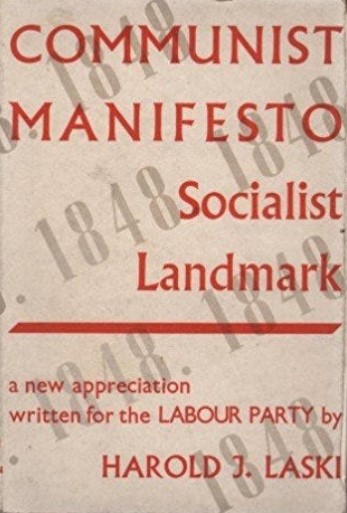

The right wing of the Labour Party like to pretend that there is no place in the Party for Marxism. But nothing could be further from the truth. The significant influence of Marx and Engels was acknowledged when the Labour Party published a centenary edition of the Communist Manifesto, in late 1947, not long after the election of the most radical Labour government we have seen, in July 1945.

The introduction to the Labour Party edition of the Manifesto was written by Harold Laski, an academic and political theorist with a history of making radical and even revolutionary-sounding speeches, to the extent that during the 1945 election campaign he was disowned by Labour leader Clem Attlee. That didn’t stop Laski being chair of the Labour Party from 1945 to 1946.

The foreword to the publication – which is reproduced in its entirety below – makes it perfectly clear that Marx and Engels were an important influence in the tradition of the Party and “an inspiration to the whole working class movement” – something the present-day right wing would prefer to forget.

Foreword to the 1947 Labour Party edition of the Communist Manifesto

In presenting this centenary volume of the Communist Manifesto, with the valuable Historical Introduction by Professor Laski, the Labour Party acknowledges its indebtedness to Marx and Engels as two men who have been the inspiration of the whole working class movement.

The British Labour Party has its roots in the history of Britain. The Levellers, Chartists, Christian Socialists, the Fabians and many other bodies, all made it possible to carry theory into practice. John Ball, Robert Owen, William Morris, Keir Hardie, John Burns, Sydney Webb, and many more British men and women have played outstanding parts in the development of socialist thought and organisation. But British socialists have never isolated themselves from their fellows on the continent of Europe. Our own ideas have been different from those of continental socialism which stemmed more directly from Marx, but we, too, have been influenced in a hundred ways by European thinkers and fighters, and, above all, by the authors of the Manifesto.

Britain played a large part in the lives and work of both Marx and Engels. Marx spent most of his adult life here and is buried in Highgate cemetery. Engels was a child of Manchester, the very symbol of capitalist industrialism. When they wrote of bourgeois exploitation they were drawing mainly on English experience.

The authors were the first to admit that principles must be applied in the light of existing conditions, but even the detailed programme they put forward is of great interest to us. Abolition of private property in land has long been a demand of the Labour movement. A heavy progressive income tax is being enforced by the present Labour government as a means of achieving social justice. We have gone far towards the abolition of the right of inheritance by our heavy death duties. Centralisation of credit in the hands of the state is partially attained in the Bank of England and other measures.

We have largely nationalised the means of communication while extending public ownership of the factories and instruments of production. We have declared the equal obligation of all to work. We are engaged in redressing the balance between town and country, between industry and agriculture. Finally, we have largely established free education for all children in publicly-owned schools. Who, remembering that these were the demands of the Manifesto, can doubt our common inspiration.

Finally, a word about the introduction. in his preface to the 1922 Russian edition of the Manifesto, Riazanov pointed out that a commentary would need to do three things:

- To give the history of the social and revolutionary movement which called the Manifesto into life as the programme of the first international communist organisation.

- To trace the genesis, the source, of the basic ideas contained in the Manifesto, to show their place in the history of thought, to bring out what was new in the philosophy of Marx and Engels, what differentiates them from earlier thinkers.

- To indicate to what extent the Manifesto stands the test of historical criticism and how far it needs amplification and correction in certain points.

Riazanov did not produce such a massive work; Professor Laski has gone far towards it, and we look forward to the further material he promises. Since his publication of Communism, twenty years ago, he has been the foremost English authority on the subject. It is unnecessary to do more than command to all the present scholarly Introduction which he has presented to the Labour Party for this special centenary edition of the Manifesto.

November 1947