By Michael Roberts

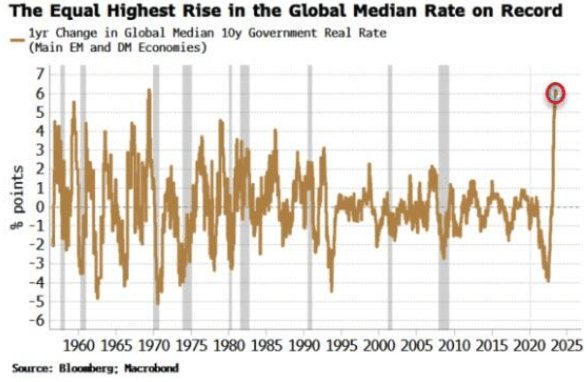

The cost of borrowing to invest or consume is reaching record levels. One benchmark for this is the real interest rate on government bonds globally. Governments are seen as the most safe borrowers, unlikely to default compared to companies or individuals. So creditors (or investors in bonds) are prepared to ask less interest return on government borrowing than they ask companies and households. Yet, even after taking into account inflation, government ten-year bond yields now have a global average of over 6%, something not seen since the late 1960s.

The reason for these high yields is two-fold. First, there is inflation itself. Rising inflation over the last two years meant that creditors want more interest to cover the loss of real worth of their bond purchases or loans. The second is the move by all the major central banks to raise their policy interest rates to levels not seen since the late 1970s. As this blog has discussed before, the central banks reckon that hiking their interest rates, which set the floor for all other borrowing rates, will eventually drive down the inflation rate back to their arbitrary target of a 2% price rise each year. With central bank rates now around 4-5% in the major economies, that feeds through to overall loan rates. Moreover, there seems little likelihood that the main central banks will reduce their rates any time before 2025.

Impact of increased cost of borrowing

This record cost of borrowing in real terms has already caused a mini-banking crisis in the US, with several smaller banks hitting the dust. And it has led to a batch of governments in so-called emerging economies to default on their loan obligations to creditors, both state and private, in the rich Western economies. And more are set to join the current defaulters.

But the other spillover from this ‘liquidity squeeze’ is the increasing risk of a new meltdown in financial markets, not dissimilar from the collapse in mortgage and speculative in the global financial crash of 2008. The financial ‘regulators are getting worried. The European Systemic Risk Board, the Bank for International Settlements and global securities regulator IOSCO have all called out the mounting risks. Referring to the claimed improvement in regulating speculation after the crash of 2008, one financial stability policymaker from that crisis era states “We never really thought that we were solving one problem and what would the knock-on be?”, arguing that regulators are now entering a “new phase”, where they have to ask “where did the risk pop out and how do we deal with that?”

Growth of unregulated ‘shadow bank’ sector

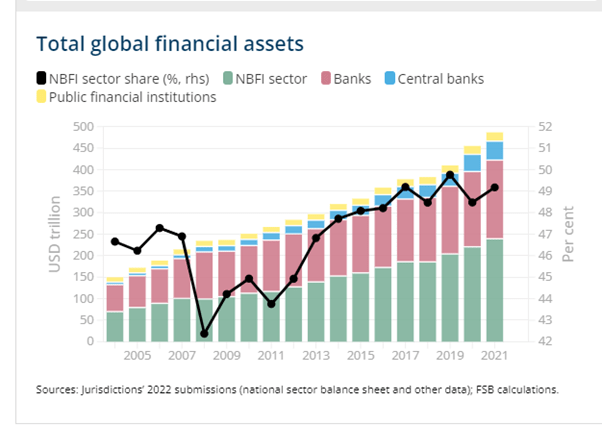

The new risk that has ‘popped out’ is with non-bank financial institutions (NBFI), comprising investment funds, insurance companies, pension funds and other financial intermediaries. These are sometimes called ‘shadow banks’. NBFIs now account for 50% of global financial services assets and they are pretty much unregulated.

Within the euro area, the growth of the NBFI sector accelerated after the global financial crisis, doubling since 2008, from €15 trillion to €31 trillion. The share of credit granted by NBFIs to euro area non-financial corporates increased from 15% in 2008 to 26% at the end of last year. Overall, the NBFI sector assets are now around 80% relative to the size of the banking sector.

Risks from Non-bank financial institutions

And here is the problem. NBFIs are prone to the risk of sudden ‘de-leveraging’ when asset prices suddenly change and become volatile. This is nothing new and is in the nature of such speculative capital. And the collapse of any large NBFI will spill over into the banking system in general. The examples are numerous: the collapse of the hedge fund Long Term Capital Management showed how financial stress in a highly leveraged NBFI can transmit directly to the large banks at the heart of the financial system.

Banks are directly connected to the NBFI sector entities via loans, securities and derivatives exposures, as well as through funding dependencies. I quote the ECB: “Funding from NBFI entities is possibly one of the most significant spillover channels from a systemic risk perspective, given that NBFI entities maintain their liquidity buffers primarily as deposits in banks and interact in the repo markets with banks.”

More recently, the collapse of the hedge fund Archegos revealed ineffectiveness of risk management and internal controls at banks, enabling NBFIs to take up excessively leveraged and concentrated positions. The now defunct Credit Suisse’s losses linked to Archegos totalled $5.5 billion. Again the ECB: “Not only was this loss substantial by itself but it was a contributing factor to the ultimate downfall of the bank, leading to its government-orchestrated acquisition by UBS.”

Bank of England highlights the risks from ‘shadow banks’

A recent report by the Bank of England concluded that: “shadow banks operate alongside commercial banks to securitize risky individual loans and hence produce standardised asset-backed securities. Investors perceive these securities, free of any idiosyncratic risk, to be nearly as safe as traditional bank deposits, and consequently purchase them. That, in turn, allows banks to expand lending by charging lower spreads.”

But then the BoE goes on to say: “In periods of stress, however, the “nearly” qualification turns out to be crucial and the imperfect substitution between securities and deposits grows apparent. Securities suddenly command a higher premium, enough to curtail the capacity of shadow banks to engage in securitization. This spills over to commercial banks: no longer able to offload part of their portfolio at the same price, they resort to increasing spreads on consumers and businesses alike.“

This affects the ‘real economy’ because “as spreads shoot up, credit becomes dearer. Indebted households must cut back on goods and housing purchases. Indebted firms must cut back on capital purchases. Employment, consumption and investment fall, causing a recession. Thus, a drop in investor confidence—we call it a market sentiment shock—produces strong and positive co-movements among the main macroeconomic variables, credit quantities, and asset prices, as well as countercyclical movements in household and business credit spreads.” This ‘market sentiment’ shock “accounts particularly well for the two Eurozone recessions in 2009 and 2012.”

Breakdown in credit can trigger a crash

In short, ‘shadow bank’ speculative lending is very liable to lead to a breakdown in credit, spreading to the wider banking sector and then into the real economy, triggering a crash. Klaas Knot, chair of the Financial Stability Board, has said that “If we want to arrive at a world where these vulnerabilities are less, we have to tackle this issue,” It was a priority because non-banks’ leverage “can potentially threaten financial stability”.

In essence, nothing has changed since Marx wrote in Volume 3 of Capital that: “if the credit system appears as the principal lever of overproduction and excessive speculation in commerce, this is simply because the reproduction process, which is elastic by nature, is now forced to its most extreme limit. A crisis must inevitably break out if credit is withdrawn.”

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.