By Michael Roberts

Last week, Zambia reached a deal for relief on nearly $4bn owed to private bondholders, raising hopes that a protracted debt restructuring by Africa’s second-largest copper producer was nearing its end. It had taken three years to get a ‘rescheduling’ of the debt. But it has not gone away, it’s just a little smaller and the servicing cost is a little lower.

This is just one example of the increasing rate of debt distress that the poorer countries of the world have got into in the last decade, particularly after the end of the pandemic.

Dependency of poorer countries on internationally-determined commodity prices

Many of these indebted countries are rich in natural resources and have young labour forces available for work. But they do not prosper because commodity prices for their exports are set for them by the international forces of the multi-nationals and trading companies. And world trade growth, particularly in resource commodities, is now contracting. For example, copper prices are down 25% in the last 12 months.

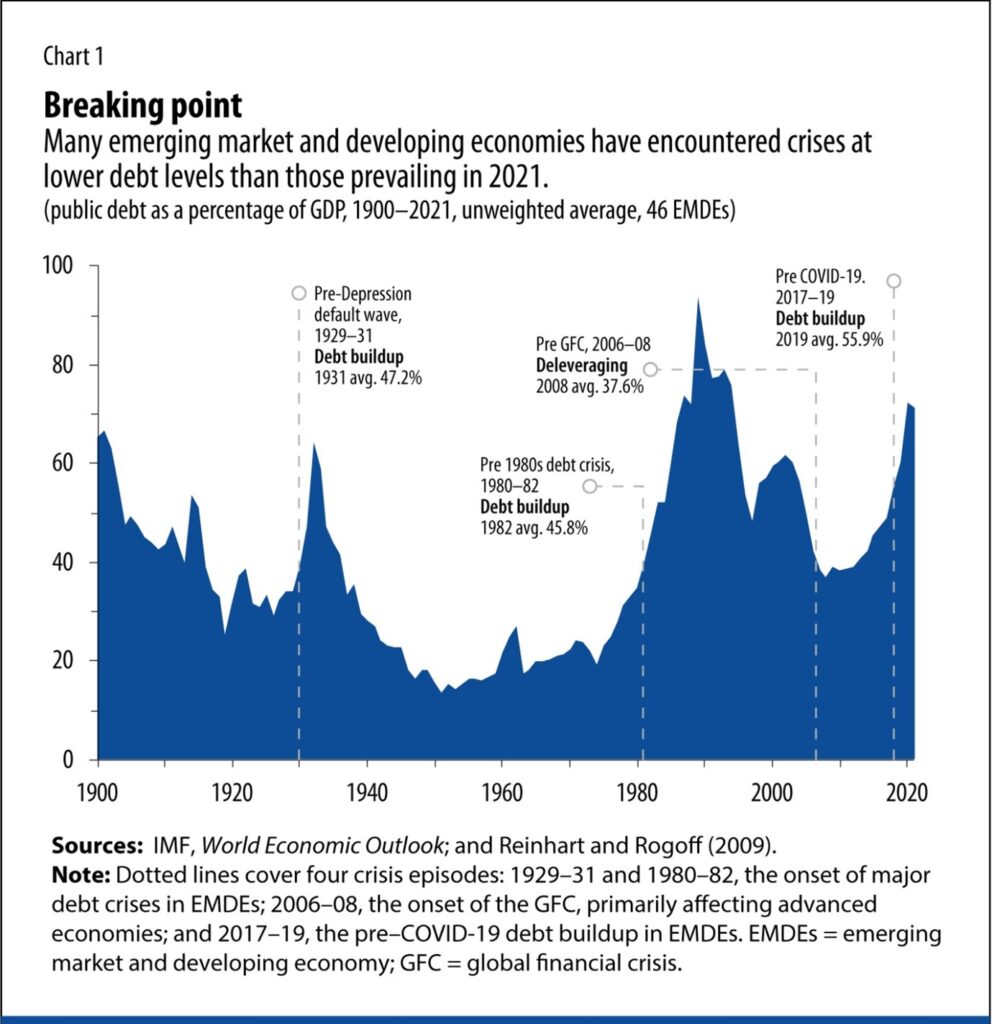

Debt owed by poor countries to the rich ones has been rising fast.

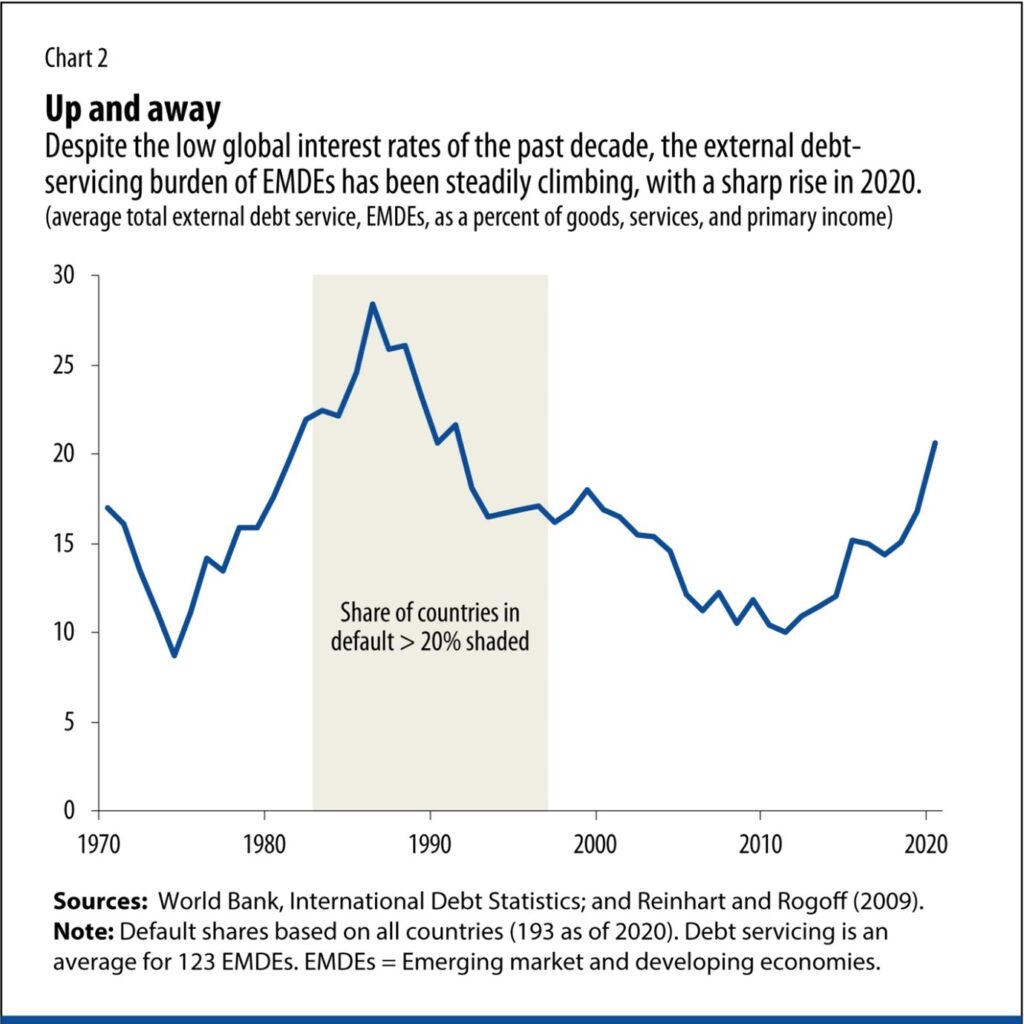

Even though interest rates on borrowing remained relatively low during the 2010s, debt servicing costs also mounted.

And since the global inflationary spike from 2021, interest rates on debt, particularly dollar-denominated debt, have risen sharply and the burden of ‘servicing’ that debt has rocketed.

Debt distress in the Global North

But it is not just in the so-called Global South that debt distress is rising. In the Global North, both the capitalist sector and governments face rising debt levels and costs in financing that debt.

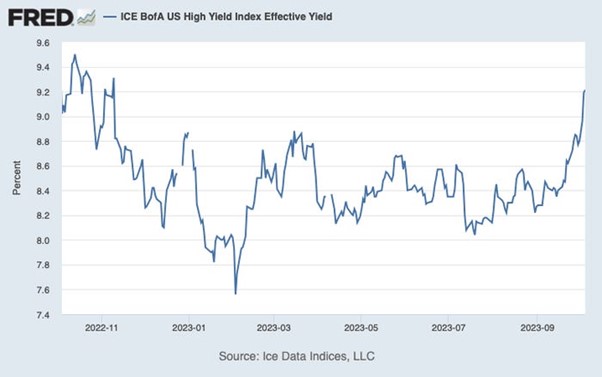

High interest rates are already starting to batter US companies, in an economy that is doing better than any other major advanced capitalist economy. Charles Schwab estimates that borrowing costs for some firms doubled or nearly tripled in 2023 compared to previous years, taking a heavy toll on corporate balance sheets. Effective yields for below-investment grade corporate debt (the debt held by the weakest companies) have soared to 9% this month, according to the ICE BofA US High Yield Index. Interest costs at US companies rose by 22% in the first quarter of 2023 compared to a year earlier.

Growth in bankruptcy filings

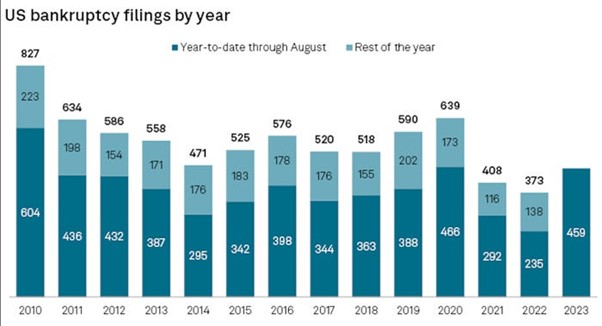

As a result, according to S&P Global, 459 companies have filed for bankruptcy as of the end of August, surpassing the total number of bankruptcy filings recorded in 2021 and 2022.

According to Deutsche Bank, total US loan defaults could rise to 11.3% of outstanding debt, only slightly lower from the all-time-high of 12% seen during the Great Recession.

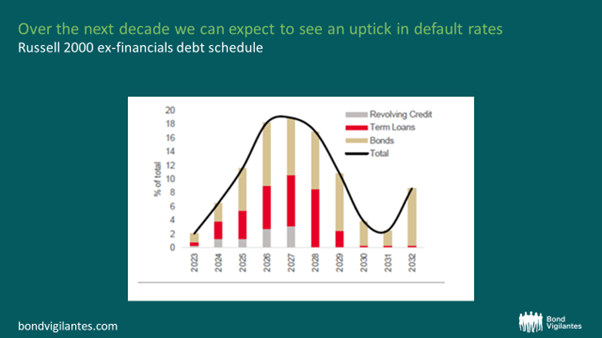

The concern is that higher rates will start to hit home from 2025 when large swathes of outstanding debt come up for renewal. The chart below shows the debt schedule of the Russell 2000 (the top 2000 companies in the US). As these firms begin to roll over their outstanding debts at significantly higher rates, defaults will pick up.

‘Zombie companies’ surviving just by borrowing more

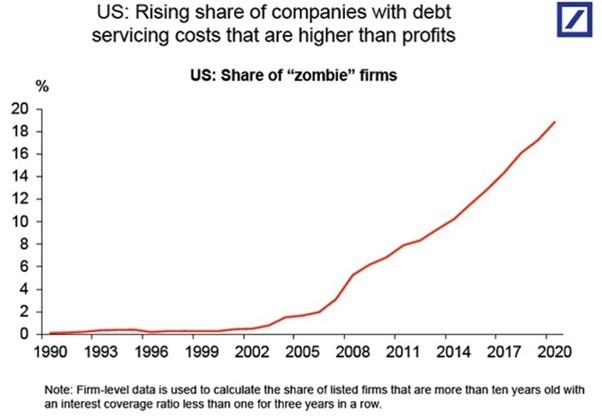

That brings us back to the so-called ‘zombie’ companies. In several previous posts, I have discussed the rise of these zombies – namely companies that do not get enough profit to service their existing debt and so survive only by borrowing yet more.

BIS economists have also discerned a new category of vulnerable companies in the major economies, which they have designated as ‘fallen angels’. These are firms on the cusp of losing their ‘investment-grade’ credit status because they have accumulated more debt than they can handle. So they are vulnerable to ‘downgrades’ in their credit status, which would sharply raise their debt servicing costs.

Estimates of zombification vary. Goldman Sachs reckoned that 13% of US-listed companies “could be considered” zombies. But the Federal Reserve found that only roughly 10% of public firms were zombie companies in 2019 using slightly more rigorous criteria. Alternatively, Deutsche Bank found that over 25% of US companies were zombies in 2020 a rise from 6% in 2000. A recent study of 4.5 million company records by Kearney from around 70,000 listed companies from 154 industries and 152 countries found that the number of zombie businesses had risen by 10% since 2021 to almost 2,000 (that would be just 3%).

If corporate defaults rise, then this will put renewed pressure on the creditors, namely the banks. There has already been a banking crisis last March that led to several small banks going under and the rest bailed out by over $100bn of emergency funding by government regulators. I have already highlighted the hidden danger of credit held by so-called ‘shadow banks’, non-banking institutions that have lent large amounts for speculative financial investments.

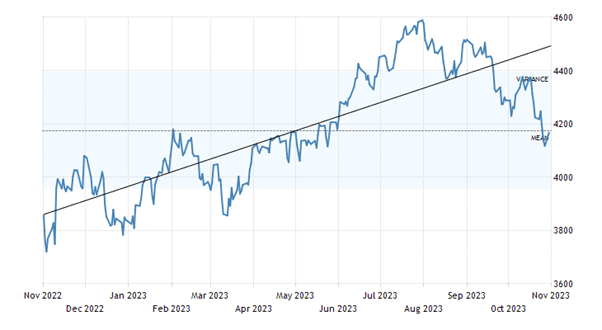

Debt servicing pressure on the US government

And it is not just the corporate sector that is coming under debt servicing pressure. So is the public sector. The US government has spent $659billion so far this year paying off the interest on its debt, as the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes dramatically raised the federal government’s cost of borrowing. It’s this slow-burn rise in debt costs and the high rate of interest on government bonds that has led to US stock market investors to start to sell. The US stock market has fallen over 10% in the last few months as the cost of borrowing has risen.

What can be done? The official answer was provided by Gita Gopinath, deputy MD at the IMF, in a recent article in the FT. Debt must be reduced, central banks must keep interest rates up (‘tight monetary policy’) and governments must reduce deficits (fiscal austerity).

Gopinath: “With record-high debt levels, higher for longer interest rates, and growth prospects at their weakest in two decades, restraint is required — even for reserve currency issuers. Indeed, the US has some of the largest deficits, at 8 per cent this year and expected to average 7 per cent over the next few years. At these rates, general government net interest payments in the US would grow from 8 per cent of revenues ($486bn) in 2019 to 12 per cent ($1.27tn) in 2028. Given the centrality of the US to global financing conditions, putting its fiscal house in order is paramount — for itself and others, who are getting hit by rising rates and weaker currencies.”

The IMF answer – raise the retirement age, cut services and privatise

And how is this to be done? Well, “entitlement reforms are inescapable” says Gopinath. That means raising retirement pension contributions and the age threshold; and cutting public services. “Many EMDEs need to reduce the footprint of state-owned enterprises, which strain the public purse and often fail to deliver effectively.” That means privatisation. And “we need to be candid: for many industrial policies, these conditions are simply not met.” That means productive development must be sacrificed for fiscal and monetary probity. Gopinath claimed that putting “fiscal houses in order is essential to ensure governments can deliver for their people.”

But is this not the wrong way round? If there were planned investment in productive sectors and government services globally, economic growth would rise, our ‘fiscal house’ would then be in order and debt distress would disappear.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.

The featured image shows Zambian President, Hakainde Hichilema, who signed the debt rescheduling deal. The image is from Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: TheophilusMaurice, CC BY-SA 4.0