By Greg Oxley, Editor, La Riposte

Over the recent period, governmental propaganda in France has once again brought fear and suspicion against Muslims to the forefront. At the start of the school year in September, the French government issued a circular banning female school students from wearing a type of dress known as an abaya, on the grounds that it was incompatible with secular public education. The new rule was widely commented on in international media outlets, raising questions about the political justification for this measure.

Shortly afterwards, French policy towards practising Muslims was further highlighted by the government’s decision to ban the wearing of hair-covering garments by French athletes in the 2024 Olympic games to be held in 2024. Numerous French female athletes have been banned from practising their sport in recent years simply because they covered their hair. Such was the case, to give but one example, with the basketball player Salimata Sylla.

Female footballers, rugby players and boxers have also been prevented from playing. Interviewed on RTL Radio, Macron’s Interior Minister, Gérald Darmanin, spuriously justified this discriminatory policy: “We don’t have to wear religious clothing when we play sports. When playing football, you don’t have to know the religion of the person in front of you.” Of course, nobody needs to know the religion of a player “in front of you”. But if you do know, what difference does it make?

The Abaya

The banning of the abaya in schools was done on the grounds that wearing it is an “ostensible sign of adherence to a religion.” This raises a number of important issues about religious freedom, discrimination, and democratic rights. The religious convictions of school students should be their own personal business, not that of the state or educational authorities.

And how is it possible to determine whether or not a particular garment is worn for religious reasons or not? Who is to say that the wearer is religious at all? Do the garments in themselves, as the government claims, have religious meaning? And if they do not, how can wearing a particular type of dress be qualified as being a sign of religious affiliation? And even if this is indeed the case, what is the problem? Just how jeans, t-shirts, short skirts, and tank tops and American baseball caps are more “republican” – i.e. compatible with the French State – than long dresses and headscarves, remains to be explained.

What is an abaya, exactly? It is a long, one-piece dress, sometimes rather plain in form and colour, sometimes more styled, colourful, and decorated. Similar garments have been worn all over the world, including in Britain and in France, for 2000 years or more. In the Arabian Peninsula, they were worn long before the advent of the Muslim faith. The idea that there is something intrinsically Muslim about them is utterly false. As with what is stereotypically considered as “western” clothing, they have been modified and restyled in a wide variety of ways, according to time and place, so that the only thing that can really be said about an abaya, as a general description, is that it is a long dress.

When garments of the abaya type are worn by actresses, pop stars, or top models, they are a fashion statement. When they are worn by school students whose names, family history, and skin colour suggest they might have some association with parts of the world where Islam is the dominant religion (including countries which were violently colonised, subjugated and exploited by French imperialism in the past), the same garment becomes a “religious statement”.

The French government claimed the ban was necessary because that there had been an “exponential increase” in reports of girls coming to school in this type of dress, and that allowing this to continue would pose a potential threat to secularism – the principle of religious neutrality – in the education system. School principals in France are expected to monitor the styles of dress in school and inform the Ministry of Education of any clothing which might be associated with religious convictions.

When schools reopened for the new term, 298 cases of girls wearing a long ample dress who were thereby suspected – presumably because of their names and colour – of making a religious statement. Of these 298 cases, which represent just 0.01% of Middle School and High School students, 67 refused to change their clothing and were refused entry into the classroom.

The government seized upon these “exponential” figures to conduct a highly mediatised campaign against the so-called Islamic threat to “French values”. The ministerial instruction to schools says that “the wearing of such outfits, which ostensibly demonstrate religious affiliation in a school environment, cannot be tolerated.”

Arbitrary Decisions and Public Humiliation

The trade union SUD-Education has published complaints by teaching staff that they are being asked to inform their management about girls who usually wear headscarves outside of school hours, so that the way they dress in school can be scrutinised. Social media posts abound with examples of everyday humiliation of school students.

At the Lycée (High School) Thiers in Marseille, where students have repeatedly denounced racist remarks by certain teachers and administrative staff, four girls were refused entry because they were wearing long dresses. One of them, unable to change her clothes on the spot, was sent home. According to one of her friends, her dress wasn’t even an abaya. “It was just a long dress. Anyway, the abaya can be just a cultural thing. I know several people that are not at all religious, but they like to wear them.” A girl called Amandine was admitted into the school wearing a long flowery dress, whereas Maryam (a popular first name in the Muslim world), wearing a similar dress was refused entry.

Girls wearing Alice-bands are asked to remove them. One girl, Anissa, having shown up in a long dress, was made to stand up in front of the whole class. The class was told that this type of garment is forbidden. The Educational Counsellor instructed her to go and find other clothes in the “lost and found” box. “They were ragged and smelly. Frankly, it was a humiliation”, says one of her friends, quoted by the media platform Marsactu.

Eight Billion Euros for Catholic Schools.

All the talk by the powers-that-be about the need to stamp out religious expression in education is in any case fraught with hypocrisy. In reality, religious education is not kept separate from the state in France. The truth is that the state provides subsidies to private religious schools on a massive scale. The same Macron government that is pursuing a policy of harassment and discrimination against Muslim school children in the name of “secularism” and “republican principles” provides the funds for no less than 7,300 Catholic schools! None of these schools could survive without state financing.

No less than 8 billion euros of public money was paid over to Catholic schools in 2022, according to figures provided by the Ministry of Education. They are only private in the sense that they escape the secular rules in force in other schools. While claiming that the slightest suggestion of any religious expression in educational establishments is inadmissible and using that supposedly intangible “principle” to harass and persecute Muslim students, the right-wing parties have always fiercely resisted any attempt to reduce or abolish public funding of Catholic schools.

For instance, when the Socialist-Communist government of 1981-1984 tried to impose restrictions on public funding of Catholic schools, they organised a massive demonstration in defence of “freedom of education” – that is to say, Catholic education! The same thing would happen today if a future left government tried to reduce or abolish this funding.

The “Islamic Headscarf Affair”

Instrumentalising religion and “cultural” issues for political purposes is nothing new. The “Islamic threat” to the so-called French way of life has been a recurrent theme of government policy for decades. The legal basis for the abaya edict is a law passed back in 2004, which in turn goes back to a campaign against Muslim school students in the so-called “Islamic headscarf affair” in 1989.

In October of that year, the Gabriel-Havez collège (Middle School) in Creil expelled three female students who refused to remove their headscarves. A few days later, the school negotiated with the families, and it was agreed that the headscarves would not be worn in the classroom. The socialist Education Minister at the time, Lionel Jospin, requested a ruling by the Council of State, which confirmed the legal right of students to manifest religious beliefs in school, but also disapproved any religious signs “having an ostentatious character” or suggesting some form of protest.

The ambiguity of these rulings left a lot of room for interpretation by decision makers, and also for arbitrary discrimination. Whereas a Muslim schoolgirl could be expelled for wearing items of clothing deemed to be religiously ostentatious, the same item worn by a non-Muslim would not be penalised. The “Creil Affair” led to a spate of expulsions and disciplinary measures against Muslim girls throughout the country.

Ever since, successive governments have exploited the wearing of headscarves, of bandanas, or of any strip of cloth even partially covering a Muslim girls’ hair, and even wide Alice-bands (seen as a sneaky way of making a religious statement, in place of a full headscarf), claiming that this represents dangerous threat to secularism and “republican values”. In 2004, under the presidency of Jacques Chirac, a new law was introduced which completely outlawed the wearing of “conspicuous religious symbols” in schools, by pupils or by staff.

The 2004 law represented a fundamental break with the guiding principles established in 1905 on the separation of Church and State. It is based on a reactionary and undemocratic version of secularism. The essential meaning of 1905 reform was that public schooling should be freed from the influence of the Church, that schools and public institutions should be neutral in religious affairs, and that any form of proselytising – advocating any particular religious doctrine – in state institutions of any kind was henceforth illegal.

At the same time, this fundamentally progressive and democratic reform guaranteed the freedom to practise any religion, or none at all. In other words, the expression or advocacy of religious beliefs by the state was outlawed, but not by individual citizens. The 2004 law distorts the idea of religion being “a private matter” by saying, in effect, that since it is private, any expression of religious convictions in public institutions is unacceptable, and forbids people attending schools, working in them or in any branch of public services from “wearing of any signs or clothing which ostensibly express a religious affiliation.” The 2004 law meant that religious neutrality was no longer limited to official institutions and public services, but was now applicable to the individual people working in them or attending schools.

Clearly, this interpretation of secularism is laden with stereotypical assumptions and reactionary prejudices. It is essentially racist in nature. The problem is not Islam. The religious question is only a Trojan horse for policies which spread suspicion and hostility towards people who may or may not be Muslims, but whose historical, cultural, and ethnic background links them in some way or other to former colonies, to present them as being alien to and incompatible with “French values” and citizenship, that they are not really part of French society.

This is just another step in the age-old strategy of “divide and rule” through which ruling classes seek to preserve and strengthen their power and privilege by designating “enemies within” on the basis of colour, ethnicity, or religion. The undoubted success of this strategy is underscored by the growth in support for the extreme right and in particular for the Rassemblement National (formerly Front National) led by Marine Le Pen. There is a real possibility that her party might win the next presidential elections.

Discrimination at Work and the Legacy of Colonialism

The restrictions placed on school students also apply to workers in public services, meaning women working for the railways, in the metro or on buses, in hospitals and nurseries, in tax offices and town halls, cannot wear a headscarf, a bandana, or any other garment deemed to have a religious connotation, whether or not they work in contact with the general public. In theory, they also apply to other religions, but it is those who are, or who are presumed to be, of the Muslim faith – and women in particular – who are the main targets. This means that a woman from a Muslim background who feels, for whatever reason, that she should wholly or partially cover her hair at work, is effectively barred from employment in the public services.

This kind of contemptuous discrimination is, again, nothing new, and is in substance a continuation of the imperialist oppression of “colonials” in the past. After the Second World War, owners and administrators of large-scale industries in France massively recruited workers from Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and elsewhere, bringing them from their homes in Africa to work as cheap labour in the factories, where, as numerous studies have shown, they were systematically put to work on the most physically exhausting and dangerous jobs.

Tens of thousands of them were employed in the car industry alone. Capitalists are not really racists, in the sense that, irrespective of colour and ethnicity, they are more than willing to exploit anyone. Racism for them is but a tool which facilitates this exploitation. So-called “guest workers” were constantly reminded of their inferior status in the eyes of their exploiters. The Carte de Séjour, a residence permit whose validity could be for as little as a few months, could be withdrawn, should any of them rebel against their conditions. Their employers did not need to sack them. The Ministry of the Interior could simply deport them.

In the publicly owned Renault factories, a manual given out to production line foremen, entitled From Douar [village, or a tiny settlement of huts or tents] to Factory, instructed them to assume the role of “educators of these people who aspire to become men of the 20th century” and to take account of their “particular psychology”, because experience had shown that their productivity was “directly proportional” to the way they are “instructed, commanded, overseen, guided, and followed.”

The entire manual was based on a stereotypical and humiliating vision of the “indigenous colonial subject”, backward and non-adapted to modernity and in dire need of the civilising influence of imperial France. The school students facing the stigmatising and humiliating injunctions of the Marcon government today are the children and grandchildren of that generation of workers. They are victims of the same institutionalised policy of discrimination, stigmatisation and humiliation suffered by their forebears.

Terrorism

State-sponsored Islamophobia has undoubtedly been made easier by the numerous terrorist attacks perpetrated in the name of Islamic fundamentalism over the last decade. The most horrific of these attacks took place in and around Paris in November 2015, when the simultaneous action of three terrorist groups affiliated to Daesh slaughtered 130 people and a further 413 were seriously injured.

Then the murder by decapitation of a teacher, Samuel Paty, in October 2020, at the hands of an 18-year-old fundamentalist fanatic, with the collusion of a parent, two students and an imam. His “crime” was to have tried to engage his students in a discussion on freedom of speech, in which he referred to the cartoons published by the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, and which led to the massacre of its editorial staff in 2015.

The murder of Samuel Paty gave rise to a wave of anti-migrant, anti-Muslim propaganda, driven by powerful right-wing media outlets, by the Macron government and all the right-wing parties, linking terrorism to French Muslims and immigration. The murder served to focus public attention specifically on the danger of fundamentalism in schools.

In the aftermath of this murder, Macron pushed through a series of new laws against “separatism”, reinforcing surveillance and controls within schools, public services, associations, sports clubs, places of worship and public demonstrations. This law was framed in such a way as to present Muslims as being hostile to democracy, secularism, and national security, “separate” from the rest of society. In fact, the people targeted by the law and the propaganda associated with it are not just Muslims, but all who are considered as culturally linked to the former French colonies in North Africa.

Failure and Complicity of the Left Leaders

Another major factor which has complicated the struggle against discriminatory policies, particularly in schools and among public service workers, has been the failure of the leaders of the Socialist and Communist parties to oppose them, going along with the idea that religious convictions should not be expressed in the public sphere and accepting the view that certain forms of clothing infer religious proselytism.

Many people on the left think that the “Islamic headscarf” symbolises oppression of women and imagine that it is imposed upon them against their will by misogynous and patriarchal fathers, husbands, and religious leaders. This is undoubtedly true in some cases, and must be fought against. However, many girls and women, for whatever cultural, traditional, or personal reasons they may have, simply choose particular forms of dress in certain contexts, and should be free to do so, without having to explain themselves or comply with dictates of state authorities.

Wherever girls or women are forced to dress in a particular way and forbidden to dress otherwise, whether it be from patriarchal and religious fanaticism, or from governments, the left should support their democratic right to choose. The reasons why they opt for “western” or “oriental” forms of dress is no-one’s business but their own.

Disciplinary measures against schoolgirls for wearing a piece of fabric around their head is an abominable act of cultural and religious discrimination, promoting and legitimising racism and marginalisation. There is not the slightest atom of progressive or democratic content in this repressive form of secularism.

Power and Control

As the 2004 law was about to be voted on in the National Assembly, Philippe Douste-Blazy, who was the general secretary of Chirac’s ruling party, blatantly explained the reasoning behind it in an interview he gave to Le Figaro. “Parliament,” he said, “must take its responsibilities. The law must prohibit, at school, the wearing of any sign of religious, philosophical, or political affiliations. From the Islamic headscarf to the Christian cross, including the yarmulke or the hammer and sickle. […] A school is not a theatre where students have the right to proclaim their beliefs or be ostentatious. It is not a place for the expression of identities. […] Schools are not, and must not be, a mirror of society.”

“Schools are an irreplaceable civic arena but have a special purpose. It aims to impart knowledge and recognition of merit. This unique mission justifies the application of special rules, different from those which prevail in the rest of society.” […] “A school is not the open street. It is an autonomous arena which must be preserved from aggressive proselytism, preserved from intolerance, preserved from controversy. It is this difference between schools and the public arena that creates confusion. Public manifestations of beliefs are permitted in the second, but they must be prohibited in the first.”

The policy of the Macron government is completely in line with the ideas expressed by Douste-Blazy. For defenders of the ruling class, public education must exclude “controversy” and political opposition. The discriminatory laws are about power and social control. The only propaganda allowed must come from the government. Public education must not reflect society as it is down below “in the street”, but only the higher interests of those in power. It must be an instrument for the unchallenged propagation of French nationalism and the perpetuation of the existing order.

The idea of “French culture” as some sort of fixed cultural norm is a myth that flies in the face of the facts. Among young people – and indeed all categories of the population – there is constant interaction, “borrowing” and adoption in what is considered as socially acceptable behaviour, in language, in clothing, in musical tastes, in sports, and in all fields of cultural and social life. Through this interaction, social attitudes and “traditions” are constantly changing. What is “French culture” and what are “French values” if not the culture and values of the real, living, multicultural and multi-ethnic society of modern France?

The nationalist ideological construction of what is and is not “really” French has many ramifications. Implicitly, and often explicitly, young people who are portrayed as not being French – even though most of their families have been in France for the best part of a century – are presented as being unwilling to “integrate” with French values and social norms. They are used as scapegoats for the deterioration of standards in public education.

Linguistically, the way they speak is said to be contaminating and undermining “pure” French. The French language is not seen as a living, changing social phenomena, but as the fruit of haughty prescriptive deliberations at the Académie Française. In truth, the real French language is the language spoken by the people of France. We have no need of ornithologists who think that birds are not tweeting correctly!

This kind of insidious Islamophobia deflects attention from the real issues in education. Throughout the country, schools in working-class areas are seriously understaffed and underfunded, while at the same time having to cope with the impact of social problems such as unemployment, poverty, and despair in their local communities, where cuts in spending have had disastrous consequences in terms of employment opportunities, housing conditions, public services, and local amenities.

Traditions of the Labour Movement

Historically, since the middle of the 19th century, the labour movement in France stood for freedom of religious practices and declared that religion to be a “private matter.” The founders of scientific socialism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, defended this same point of view. By asserting the private nature of religious beliefs, the labour movement strove to resist state interference in religious affairs and defend the right to freely practise any religion or to have religion at all.

At the time of the First International, founded in 1864, Marx and Engels considered that the “separation of Church and State” would be a step forward. However, they were categorically opposed to the repressive “anticlericalism” by which the capitalist class, under the Third Republic in France and under Bismarck in Germany sought to consolidate the position of the ruling elite. In practice, under the guise secular demagogy, the anticlericalism of the time led to persecution of certain sections of society and to divide workers among themselves on religious grounds.

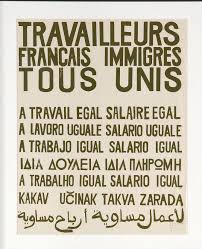

Then as now, the entire workers’ movement and anyone concerned with the defence of democracy and the struggle against racism has a duty to take a firm stand against all forms of discrimination, which, as we have seen, are rooted in the history of colonial oppression.

The banning of headscarves and abayas issues for school students, like the discriminatory measures taken against Muslim women in sports, outrageous as they are, are only the tip of the iceberg. They are a means of signalling that people of colour, even those whose parents and grandparents were born in France, are a “race” apart and to be considered as inferior. They are discriminated against when applying for jobs. They are singled out by the police for special attention, suffering arbitrary arrest and detention, beatings, sexual harassment, and all too often mutilation and murder.

All these forms of oppression are part of a system, backed up by an arsenal of laws and longstanding practices used by state authorities striving to consolidate their social basis by rallying the “French” around themselves, in opposition to cultures which they present as alien and dangerous.

Racism, Capitalism and Socialism

Racism is not, at root, a moral question. It is a conscious and necessary strategy, of vital importance to those in power, in which huge material interests are at stake. This is especially true at a time when their system can only thrive at the expense of the living conditions and democratic rights of the mass of the population. Inflation and insatiable quest for ever-greater profits are wearing down the poor and undermining all the social conquests of previous generations of workers.

There is a tremendous shortage of affordable housing. Hospitals and schools suffer from a chronic lack staff and resources. Social Security and pensions are constantly under attack. Unemployment is high. People are worried about the future.

In such conditions, the resentments and prejudices harboured by some workers as to who should “have” and who should “have not” and which are played on and exacerbated by nationalist propaganda can only be overcome by uniting them around socialist policies which strike at root causes of exploitation, inequality and declining living standards, namely private ownership of industry, banking, and the capitalist system as a whole.

The struggle against Islamophobia and all forms of racism can find expression in a wide range of immediate demands and slogans. But these must be linked to a broader struggle to change society, by breaking with capitalism. Only then can we hope to reduce competition between workers and unify them in a common struggle, towards the establishment of a new social order, based on the common ownership of the economy and democratic and fraternal cooperation to the benefit of all.