The Autumn statement of Tory Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, outlining future government taxation plans, will make little difference to the likelihood of a Tory defeat at the next general election. Indeed, a cynic might conclude that having given up on the possibility of winning, Hunt is happy lavish tax concessions on the Tories’ friends in big business; handing out the dosh, so to speak, while the going is good.

The meagre offerings to those who work for a living – like the increase in the national living wage, the small reduction in National Insurance contributions and the uptick in Universal Credit – will make only a minor dent in the cuts in living standards that workers have already experienced, in what has been the biggest squeeze for generations. A pound or two here and there makes little difference when key costs faced by workers – rents, mortgages, energy, food and transport – have been going up by a minimum of 10% a year, and in some cases well above that.

It may have escaped Jeremy Hunt’s notice, but while headline inflation comes down, it does not mean that prices come down, merely that they are still rising, albeit at a slower rate. Most working families are still struggling to keep up with the rises of the past few years. Taking energy alone, gas is about 60% more expensive than two years ago, and electricity around 40% more. Even according to the government’s own figures, a third of adults are finding housing costs either “very” or “somewhat” difficult to afford.

The real headline of the Chancellor’s Autumn statement was not the handful of crumbs he threw to working people, but the much bigger tax concessions given to big business. Hunt even referred to them as “the largest business tax cut in modern British history”. It will mean allowing companies to offset any investment against future profits and the cost to the Exchequer will run into tens of billions of pounds.

On past performance, this business ‘welfare’ will make little difference to the trajectory of the economy. Even while Hunt was making his statement in the House of Commons, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicted that the UK economy would grow by a miserable 0.6% this year, and only 0.7% next.

Growth will rise to the dizzy heights of 1.7% in five years time.

Growth will rise to the dizzy heights of 1.4% in 2025, then 1.9% in 2026, 2% in 2027 and 1.7% in 2028. The Bank of England, too, has predicted an economy flatlining next year. Price rises, the OBR predicts, will not return to ‘normal’ for at least two years. Hunt may boast in his speech that the Tory government is “back on track”, but it is clearly ‘on track’ to more austerity and more cuts in living standards in the future.

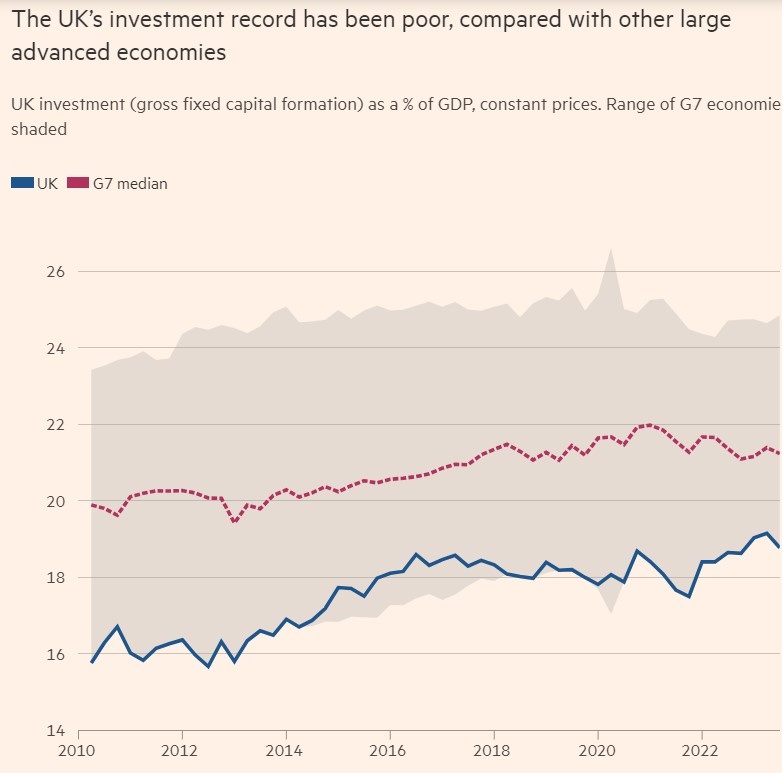

The supposed aim of the tax hand-outs to business are to promote increased investment in the British economy, and indeed a lack of investment has been at the core of the decline of British capitalism over decades. Britain has suffered from a chronic lack of productive investment, as the rich and powerful have preferred to invest their wealth in property, speculative financial ventures, and overseas. Anywhere, but in the development of domestic infrastructure, or in a manufacturing or industrial base. As in the past, these new concessions will have loopholes built in, to permit tax offsets for all manner of dubious and unproductive ‘investments’.

It is that long term lack of investment in the productive sectors of the British economy which has condemned the population to declining living standards, a crumbling infrastructure and the withering-away of public services. Compared to the other main countries of capitalism, the OECD, the British economy has done much worse.

“Data from the OECD”, the Financial Times explains, “show that between 2007 and 2022, labour productivity grew less in the UK than in the US and was below the average in the club of richer countries. Total factor productivity, an alternative measure that attempts to capture how efficiently resources are being used, rose by a mere 1.7 per cent between 2007 and last year, according to UK government statistics…”

“UK business investment has grown only 4.6 per cent since the start of 2016 when it began stagnating — in part reflecting high uncertainty following the Brexit referendum. By contrast, there has been a 32 per cent expansion in US business investment since the start of 2016 and 15 per cent growth in the eurozone, according to data collected by Oxford Economics…”

Presiding over a stagnation nation

As an article in the Financial Times aptly put it, “…the challenge for Hunt is that he is presiding over a stagnation nation…Taxes are at a 70-year high, yet some 7.7mn people are on hospital waiting lists, schools are crumbling and ministers want to rent space in foreign jails because UK prisons are full”.

Future spending and taxation plans by the Tories – already baked in by previous budget statements and largely unaffected by this Autumn statement – present a dire picture of continued austerity into the forseeable future. The Resolution Foundation think-tank has warned that future spending plans will bring in “implausibly” steep cuts in the future.

According to the Financial Times article on the stagnation nation, “Spending per person in departments such as the Home Office; Transport; Justice; and Levelling Up, Housing and Communities is set to fall in real terms by 16 per cent, or £20bn a year, between 2022-23 and 2027-28, it says. That would mean cuts being implemented ‘at a similar pace to those overseen by George Osborne in the early 2010s’, a reference to the former Tory chancellor’s austerity programme after the financial crash.” In other words, perpetual austerity as far as the eye can see.

It is important for us to understand that this, broadly speaking, is the economic scenario that will be faced by an incoming Starmer/Reeves government, if, as seems likely, Labour wins the next election. As long as the Labour leadership base their economic policies on the continuation on the market system, based as it is on greed and profit, they will be the prisoners of that system, forced to implement a ‘Labour’ version of austerity.

“No room for gradualism” in British politics and economics

In many respects, it may even be worse than the Tories’ initial austerity from 2010. As the Financial Times correspondent noted, “The difference is that when Osborne became chancellor in 2010, hospitals and schools had just enjoyed a long spell of increased spending under Tony Blair’s Labour government”. There was more ‘fat on the bone’ as it were. Moreover, in 2010, net public sector debt was 65 per of national income and interests rates were low. Labour will inherit a public sector debt not far off 100% of national income, with interest rates much higher.

As one would expect from the most serious newspaper of British capitalism, the Financtial Times pulls no punches: “The bottom line is that in an era of low growth and precious little money, a Labour government would be just as dependent as the Conservatives on getting the economy growing before it can start to make traditional big choices on tax and spend”.

Jeremy Hunt might be moving the deck chairs around on the Titanic, but Labour will inherit the same passenger liner, in the same iceberg-strewn seas. Workers cannot afford for Starmer to just be shuffing around the same deck chairs.

It was a populist of the hard-right, the Argentine president-elect Javier Milei, who suggested that “there is no room for gradualism”. What that implies in terms of his policy solutions are a million miles removed from what Argentine workers need. But as a broad statement, and specifically applied to British society, it is completely correct.

There is no longer any room for gradualism in British politics and economics. The choice will be a simple one: between a Labour government that follows the dictates of a rotten system, dragging us all into more austerity. Or a labour movement mobilised with a leadership that challenges the basic tenets and structures of the system and offering the hope of something different.