By Cain O’Mahony. This is the first of a three-part series of articles on the Hungarian Revolution of 1919. Part II can be read here and Part III here] [Featured photo shows soldiers with ‘aster’ flowers in their caps and uniforms]

******

The Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919 was an extraordinary episode in history, in that a ruling class voluntarily handed over power to the revolutionary masses without a struggle. Sadly, however, because of the inexperience of the young Bolsheviks at the head of the movement, the revolution was lost because of both ultra-leftism and opportunism.

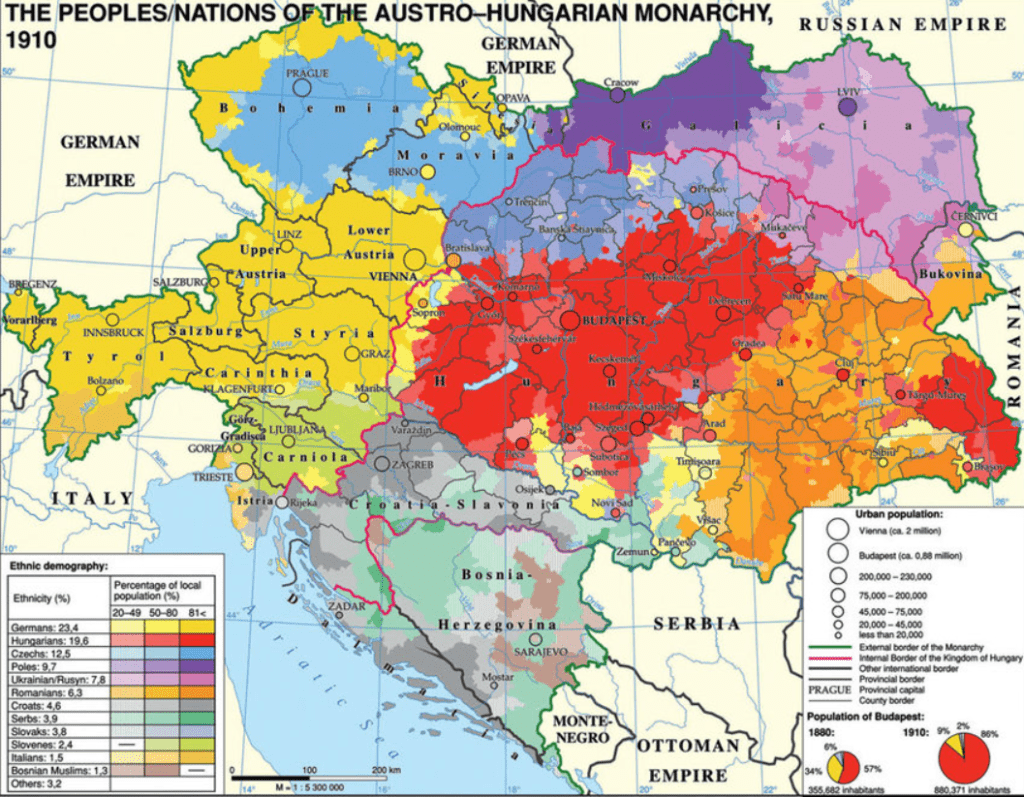

Hungary at the turn of the 20th century was a semi-feudal backwater, the junior partner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Throughout much of its existence it had been an occupied country, despite several uprisings to secure independence. The simmering nationalist aspiration of Hungary resulted from centuries of subjugation by both Hapsburg and Ottoman empires.

It was also at the crossroads of Eastern Europe, which meant various peoples flowed in and out of its borders. Eastern European countries have historically had very fluid borders, due to centuries of competing empires, war, occupation, invasion, pogroms, famine and revolutions, a process still going onto this day. I have worked extensively in the north west corner of Romania where it borders Hungary and Ukraine, and this was brought home to me by a Romanian colleague who explained he lived in the same farm house his family built over 150 years ago. He often joked: “My grandparents were born subjects of the Austrian Hapsburgs, my parents were Hungarian citizens, and today I am a Romanian. And we never moved house once!”

Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1910

In the late 19th century, the Austrian monarchy, however, had to draw Hungary closer to its Court after Austria’s defeat by Prussia, marking the rise of German power. The nationalist aspirations at the top of the nascent Hungarian bourgeoisie were bought off by the ‘Ausgleich’ – the ‘compromise’ – where Hungary became an apparent partner in the remodelled ‘Austro-Hungarian Empire’.

The Hungarian aristocracy of numerous counts and barons were brought off with huge estates – by the arrival of the 20th century, 85 per cent of the land was owned by a mere 5 per cent of the population.

Neither was there any democracy – the Austrian Emperor allowed a ‘Parliament’, but only 6 per cent of the population had the vote: that is, the aristrocracy. Even then, the Emperor chose who could be ‘Prime Minister’.

Meanwhile, their nationalism was pandered to with a form of apartheid that introduced three rigid castes – 1st class citizens were Austrians and ethnic Hungarians, 2nd class citizens were Croats and Poles, and the 3rd class, the peoples with no rights at all, were the Czechs, Slovaks, Romanians, Ruthenians, Slovenes and Serbs.

Divide and rule

Incidentally, this ‘divide and rule’ construct has left a legacy of inter-communal ethnic violence over the decades, just as British colonial rule has done in the Indian sub-continent. Ethnic conflict has flared up continually in eastern Europe and the Balkans, whenever reaction takes hold, whether that means, of course, the Holocaust, or the atrocities inflicted upon each other by the Ukrainian and Polish border communities at the end of World War II, or the horrors of the Yugoslavian civil war in the 1990s.

In Hungary in 1910, the national census discovered that of the 21 million people living within Hungary’s borders, only 10 million were ethnic Hungarians, meaning over half the population had little or no rights at all, and faced discrimination in employment, education, and housing.

The vast majority of the population were the peasantry and agrarian workers, who faced a life of grinding poverty and virtual serfdom, tied to the huge estates. It was said the only time a Hungarian peasant wore boots was if he joined the army.

Industrialisation came late to Hungary, although by the turn of the 20th century, factories rapidly grew around the main city centres of Budapest and the second city of Szeged, with many counts and barons moving into the new world of capital. Yet Hungarian capitalism was still entirely dependent on the senior partner of Austria, and increasingly the new Germany. Of the 82 cartels that controlled the Hungarian economy, only 26 were Hungarian owned – not that the conditions in the workplace fared any better for the workers in those companies run by their Hungarian compatriots.

The peasantry, by the very nature of their existence of being scattered across the vast estates, could not develop a collective consciousness, and their traditional mode of political defence was anarchism, of explosive but directionless uprisings, or substituting class action with acts of individual terrorism, in the style of the Russian Narodniks.

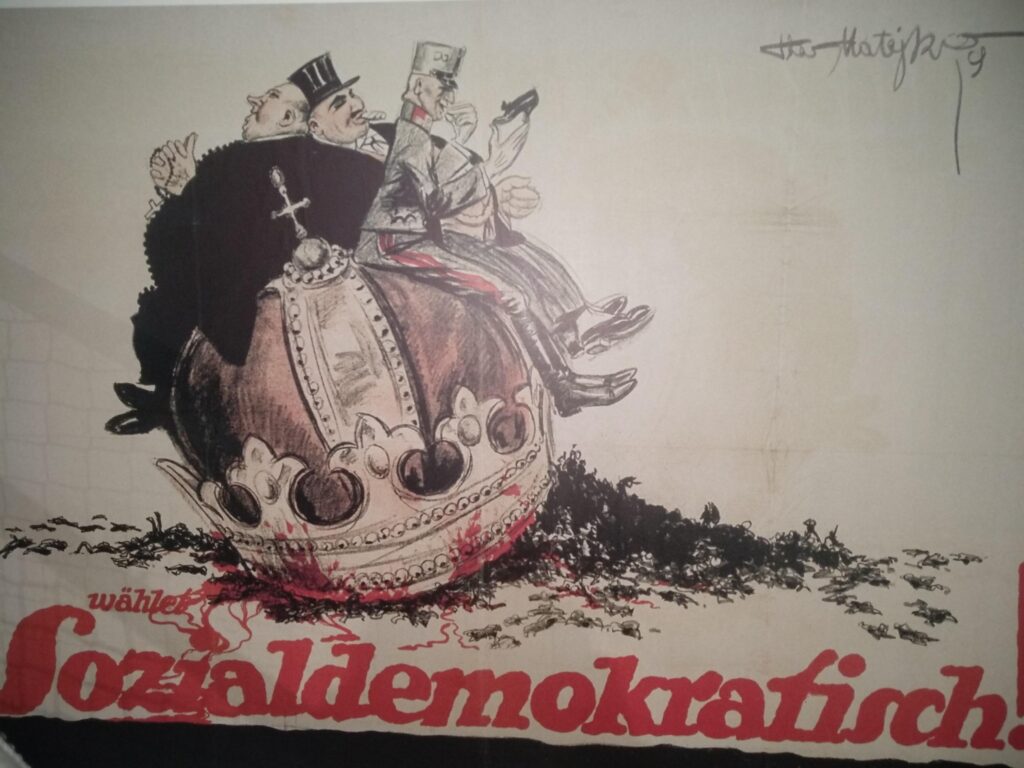

The rapid industrialisation, however, saw an equally rapid political awakening, with the workers being collectivised in the hell-hole industrial complexes. This led to a massive growth in trade unionism, and with it, its political wing, a new Social Democratic Party. However, many of the new proletariat were yesterday’s peasants, who had flocked to the cities to escape the serfdom of the old estates, and they brought with them their anarcho-syndicalist ideas.

There had been the beginnings of a Marxist current, around the translator of Karl Marx’s works, Ervin Szabo, but they became discredited within the SDP after the failure of the 1905 Russian Revolution, and they were driven out by the SDP’s right wing leadership.

So by the time of the outbreak of World War I, the left forces of Hungarian society were basically divided into two different tranches – reformism or anarcho-syndicalism. There were no Marxist or Bolshevik organisations in Hungary.

Austro-Marxists

For the SDP and trade union leaders, as they grew more comfortable in their new positions of power, so they saw accommodation with the need for a bourgeois revolution for Hungary, very much influenced by the ideas of the Austro-Marxists (see ‘The historic failure of Austro-Marxism and the fall of Red Vienna’, posted 15 October, 2021). It would be liberation by stages – first the ‘national revolution’ to throw off the shackles of the Austrian imperialists, then the introduction of universal suffrage and a parliament with free elections, and when the SDP won a majority, then and only then there could be the socialist transformation.

Much of the rank and file of the SDP and trade unions, though, still had a strong streak of anarcho-syndicalism within their outlook, and saw mass action and strikes as the way to beat reforms out of the ruling class: indeed the SDP and its youth section had an organised anarchist tendency within it, led by Tibor Szamuely.

But as a result, neither wing had a worked out socialist programme or strategy, and subsequently in the coming tumultuous events they just kept running into a brick wall.

The rapid industrialisation convinced the Austro-Hungarian imperialists that their war in 1914 against Serbia would be a short, sharp victory, one they could finance through existing stocks and shares.

Instead, Austro-Hungary sparked the conflagration, that engulfed all of Europe, the mass slaughter of World War I.

It proved a disaster for Hungary. The Empire’s defeat in 1918 left Hungary with 700,000 dead, its currency halved in value and agricultural production declined by half. Meanwhile the western allies and their new partners circled the country for a carve-up of its land, that would see it lose 75 per cent of its territory and 3.5 million ethnic Hungarians now minorities in other lands.

From 1915 onwards, throughout the war years, Budapest and Szeged were racked by general strikes, either for improved working conditions or against the war. As the war ground towards an inevitable defeat for Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Hungarian masses were then electrified by the revolution in Russia in 1917 – they had witnessed the Tsar and his empire brought crashing to the ground and replaced by a socialist government. The order of the day now was not just to strike, but form soviets, or workers’ councils in the Russian style, and also soldiers councils in the rapidly collapsing 1.4 million-strong Hungarian Army.

Workers councils

The first workers council appeared on 26 December, 1917, set up by a new movement called the ‘Engineer Socialists’. Without support from the SDP leaders, anti-war SDP members from the engineering, metal-working and technical sectors set up a new trade union to co-ordinate strikes and protests, and they became the epicentre of the growing Workers Council movement.

The largest explosion of anger came in January 1918, in solidarity with the Russian Revolution, when news spread of the punitive terms Germany was demanding of young Soviet Russia in the Brest-Litovsk negotiations. Strikes by the Engineer Socialists were joined by railway workers, and a mass protest of 150,000 was held in Budapest under the slogans of ‘Long Live the Workers Councils’ and ‘Greetings to Soviet Russia’.

This was only the start of the unrest to follow, with wildcat strikes, mutinies in the Army, and all the time, the gulf between the right wing SDP leaders and the left wing Engineer Socialists deepened.

With the entry of the US into the war in 1917, President Wilson drew up his 14 point plan that would later result in the League of Nations, but which also included the call for ‘the right of small nations to be free’.

The Wilsonian Doctrine originally had a dual aim. Primarily, it was for domestic consumption. The US had been isolationist as World War I raged, with the US masses rightly seeing it as the ‘old world’ imperialist orders slugging it out for a new carve up of their colonies; it was not their war. To ‘sell’ the USA’s entry into the war to the American public, it had to be presented as a ‘war to defend democracy’. The second aim was to destabilise the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and the Ottoman Empire too) by provoking nationalist uprisings in those ‘small nations’ they ruled.

However, the Russian Revolution gave the Wilsonian Doctrine a new urgent aim – to create ‘safe’ mini-states to act as a ‘White’ bulwark against the rapid rise and spread of Bolshevism. Yes, they wanted Austro-Hungarian imperialism dismantled, but not for it to be replaced by ‘unsafe’ Bolshevism.

Realising the danger posed by President Wilson’s doctrine to their rule, the Austro-Hungarian imperialists around the court of Emperor Charles IV desperately offered a sop in October 1918, allowing the bourgeois nationalists in what would become Czechoslovakia, Slovenia, Romania and the Southern Slavs (Yugoslavia) to form National Councils, but still supposedly under Austro-Hungarian rule. This backfired totally – all National Councils immediately voted for secession.

The Viennese court thought they could hang onto Hungary however, as the Hungarian bourgeois fortunes were tightly bound up with Austrian and German finance, as seen by the ownership of the cartels. There would be no National Council for Hungary. Numerous Prime Ministers came to try and defend their allegiance to the Empire and their opposition to democratic reforms, but were all left twisting and turning in the wind because the real power in Hungarian society had transferred to the streets – and the streets wanted a Hungarian National Council, and one that included the opposition parties, not just the mass-based SDP but also the forces of Count Karolyi.

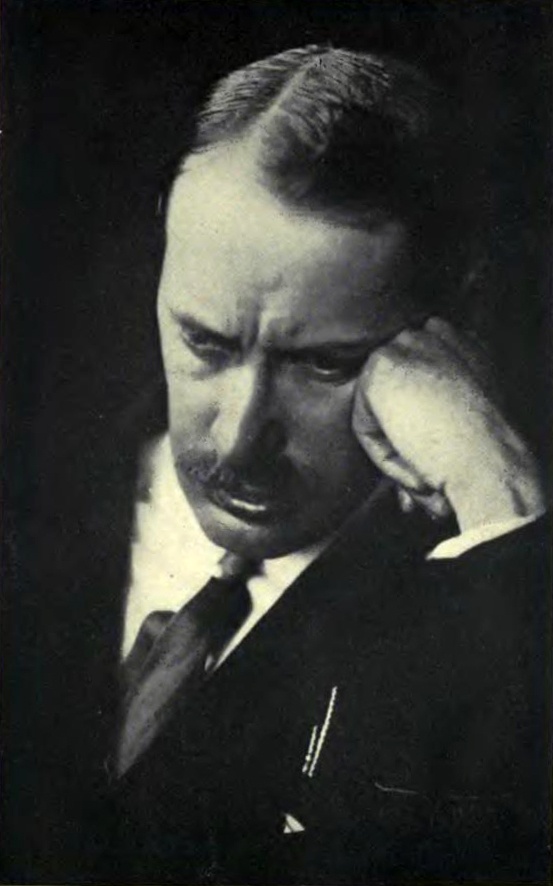

Count Karolyi

Count Karolyi was a progressive bourgeois who wanted a Republican parliamentary system and had formed the Party of Independence in 1915, arguing for Hungary to switch sides and go over to the Allies. He was despised by his fellow counts and barons who derided him as the ‘Red Count’ and later, the ‘Hungarian Kerensky’.

But real power had already transferred to the streets. Budapest was by now virtually a commune, as all the workers councils and strikers joined together. More importantly, as the Bulgarian Front collapsed, the striking workers were joined by 300,000 either demobbed or deserting troops who flooded into the city. They had retained not only their rifles, but artillery as well.

Due to the pressure, the pro-Imperialist government finally collapsed on 23 October 1918. It was clear to all that Karolyi was the only viable alternative. Assuming they were about to be summoned by the Emporer to form a government, they formed their own Hungarian National Council made up of Karolyi’s supporters and the SDP, and set up their headquarters in the Hotel Astoria on the Pest side of the city, waiting patiently for a summons from the Emporer to announce the bourgieos revolution.

And they waited. The days dragged by, and thousands thronged around the Hotel awaiting news. Tensions mounted when huge crowds crossed from the Pest side to march on the seat of imperial power, Buda Castle, to demand the National Council take power. As they crossed the famous Chain Bridge that links the two sides of the city, the Imperial Police opened fire, killing three people and wounding a further 50.

This left Budapest a city on the edge all week, but it finally erupted on 30 October 1918. Emperor Charles IV did not finally announce Karolyi as the new Prime Minister as everyone across Hungarian society had anticipated. Instead, he gambled on one last throw of the dice and appointed the pro-imperialist Janos Hadik as PM instead.

The response of the masses was swift and explosive. Soldiers tore off the Imperialist ‘rose’ emblems from their uniforms and replaced them with ‘aster’ flowers in their caps, in a demonstration of support for the National Council sitting in the Hotel Astoria. Revolutionary soldiers took over all key points in the city. The trade unions and workers councils meanwhile, secured all rail transport, telephone exchanges, Post Offices and banks.

The imperialists sent in their renowned Field Marshal, the Baron of Somorja, with his elite Landswehr Division into Budapest to ‘restore order’. He was promptly arrested by the National Council while his troops evaporated away into the mass of cheering crowds. The former imperialist Prime Minister, the hated Istvan Tisza who had been PM for most of the war and was seen as a rallying point for reaction, was also assassinated that day.

On 31 October, Hadik bowed to the inevitable and informed the Emperor he had resigned (never mind Liz Truss and her 44 days – Hadik as Prime Minister lasted just 17 hours!).

Hungarian Republic

The court of Charles IV fled to Vienna, and Karolyi and the National Council took power, announcing the formation of the Hungarian Republic and parliamentary democracy. The nascent Hungarian bourgeoisie now rallied around the formerly despised Karolyi, their next line of defence of their cartels, land ownership and profits. They had no choice. Karolyi was the only one of their class that had demonstrated democratic credentials. They were all ‘democrats’ now.

First President of Hungary

In reality, all that Karolyi and the right wing SDP leaders governed was a power vaccuum. Imperialism had collapsed, and the only real power was the masses out there in the workers councils. Karolyi merely inherited all the problems and ruin left behind by the former Empire, but had no policies or programme to solve it.

Unfortunately too for Karolyi, the western allies demonstrated the same belligerence to Austro-Hungary as it had to Germany – in Germany there were to be massive reparations and the stifling of its economy, while for Hungary it would be eaten away by land-grabs by its neighbours, to fulfil the Wilsonian doctrine.

Karolyi’s support for ‘western democracy’ was rewarded by President Wilson demanding the Hungarian armed forces disarm. Karolyi slavishly agreed, hoping for Western support for the new Republic. Instead, with Hungary now totally disarmed, and with a nod from the Western Allies, Hungary’s neighbours began to dismember the country. On 5 November 1918 the Serbian army backed by French troops invaded the south. On 8 November, the Czechoslovakian army invaded the north. On 18 November, the Romanian army invaded in the east.

President Wilson’s plan to create a ‘White bulwark’ against Soviet Russia was underway, and Hungary was considered far too unstable and revolutionary to be trusted to be part of this coalition. There was fury amongst the Hungarian bourgeois and socialists alike at Karolyi’s naivety. He was now totally discredited.

As the carve up continued over the next few months, the final hammer blow came on 20 March 1919, when the Western Allies now demanded that the Hungarians must evacuate the border cities of Debrecan and Mako, and hand them over to their neighbours.

Any hopes of survival by the Hungarian bourgeois finally evaporated – the ‘bourgeois revolution’ had been still-born: they had run out of options and effectively gave up. Karolyi said the only force now capable of forming a government were the SDP. He resigned, issuing a statement saying that he had given up his powers to a ‘new government of the proletariat’.

Communist Party – Bela Kun

By now, a new political force had arrived – the Bolsheviks. Led by Bela Kun, in November 1918 they had established the ‘Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja‘ – the ‘Party of Communists from Hungary’ And now the ruling class wanted to hand them power.

Such was their desperation that the Hungarian bourgeois – along with much of the SDP leadership – thought that by putting the Bolshevik Kun at the head of a government, perhaps the new Russian Red Army would come to Hungary’s aid. Incredibly, the counts, the barons, the land owners, the cartels, the bourgeois democrats and the right wing reformist SDP and trade union leaders saw their only salvation in ‘liberation’ by the Russian Bolsheviks. It was the wildest of cards, but the only one they had left.