By Ray Goodspeed (Leyton and Wanstead Labour member)

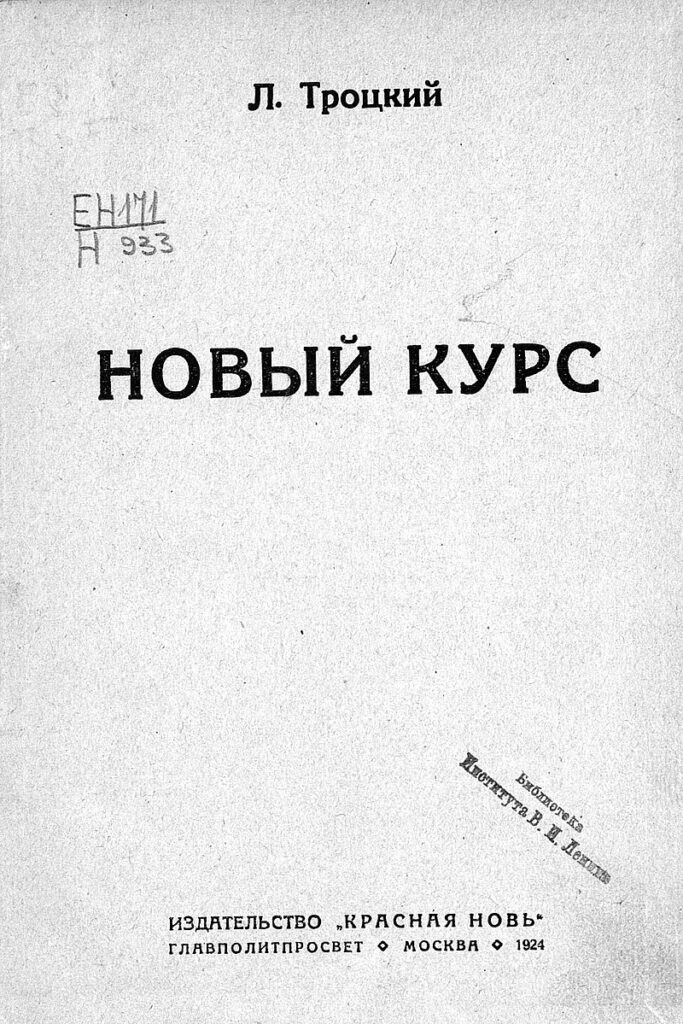

This month is the centenary of the publication in 1924 of Lev (Leon) Trotsky’s The New Course, one of the founding documents of what would become the Left Opposition to the increasing bureaucratisation and lack of democracy of the Russian state and of the Communist (Bolshevik) Party itself, which culminated in the appalling horrors of Stalinism. Trotsky would carry on that struggle until his assassination in 1940, in exile in Mexico, at the hands of a Stalinist agent.

[The full text can be read on the Marxist Internet Archive here.]

At the time of writing The New Course, Trotsky had enormous prestige both as the architect and leader, with Lenin, of the October Revolution in 1917, and especially as the creator and commander of the Red Army, which had achieved a hard fought and unexpected victory in the brutal Civil War which had only ended in the Spring of 1921.

The New Course is a collection of articles and letters to the Russian Communist press that Trotsky wrote in December 1923 and January 1924, brought together in one volume. In it, he pointed out the dangers of the party membership becoming increasingly merged with the state apparatus, made up of officials and administrators, rather than being comprised of the industrial workers who it claimed to represent. Such workers made up only one sixth of the Communist Party membership at the time.

The bulk of party members were either state bureaucrats, peasants or those studying. Under the pressure of the Civil War, which was an existential crisis for the new workers’ state, thousands of workers had left the factories to fight and to die to preserve the revolution. Thousands of others had to be drafted into actually running the state machine, itself appointed by increasingly top-down procedures.

The workers’ councils, or soviets, had become rubber stamps for decisions taken by the system of party secretaries that ran the state, with Stalin himself at the top of the pyramid. Despite them often having a working-class background, Trotsky noted that these officials had become a specific “type” of time-servers, with their own interests and privileges to protect.

Divide between workers and their party

Trotsky identified the urgent need for regenerating the industrial economy and boosting the numbers of workers – proletarians – and encouraging a flow of these into the Party, so it could once again become the party of the workers. Its drift away from that had led to a clear divide opening up between the workers and their party, leading to industrial unrest, strikes and protests.

This was even more crucial, as the Communist Party was the only party in a one-party state, a situation that had been imposed during the Civil War and still remained. Workers were leaving the party or even joining “anti-party” workers groups. This risked detaching the party from the masses and weakening its class character.

This was in the context of the (necessary) decision to partially restore some elements of market capitalism under the New Economic Policy (NEP) from March 2021 onwards. The number of unemployed workers had increased by seven times in the two years up to January 2024, reaching 1,240,000, and there was a lowering of wages as the new bosses (‘Nepmen’) tried to boost their profits.

Further, Trotsky noted, there was an increasing intolerance of any dissent, with decisions being enforced through demands for blind loyalty to the leadership and through intimidation, with free-thinking members being accused of ‘factionalism’. He writes of an atmosphere of “cliquishness, smugness and disdain”, where decisions are made by the “upper storey” of the party while the “lower storey” merely learn of decisions which they then have to implement.

Young workers and students, in particular, were being trained in a spirit of deference to authority. Those who tolerated that were then groomed for future places in the hierarchy, but others were angered and drifted away from the party or were driven to factionalism. Of course, the older Bolshevik leaders rightly carried huge personal respect on account of their past roles, but in Trotsky’s view, this should never mean unquestioning obedience.

Old-Bolsheviks

New members who joined more recently – since the October Revolution – had their own experience to draw upon and should have the right to “participate most actively” in deciding policy. The so-called “Old Bolsheviks” needed to work with the new layers or risk becoming the “consummate expression of bureaucratism”.

Both Lenin and Trotsky had become concerned about this developing situation, and especially after a series of disputes with Stalin in 1922, around issues such as the national question in Georgia, Lenin had agreed to work with Trotsky to reform the party and move against Stalin’s concentration of administrative power into his own hands and his misuse of that power.

In May 1922, Lenin had been weakened by the first of a number of strokes, but nevertheless, he was working with Trotsky to prepare “a bomb” for Stalin at the 12th Party Congress, in March 2023. On March 10, however, Lenin suffered a second, and much worse, stroke which left him partially paralysed and unable to play any further active role in politics. He was unable to take part in the Congress. This left Trotsky isolated and, for good or ill, he decided not to force the issue with the main leaders, Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev – the so-called “Troika” (named after traditional Russian three-horse carriage).

Despite Trotsky’s huge popularity after the Civil War, especially within the Red Army, and despite, or even because of, his charisma and fine oratory, those who wanted to engage in a factional dispute with him inside the Communist Party itself, which held all the real power, could focus on a number of weaknesses. This they did, ruthlessly, and much more easily in Lenin’s absence. Trotsky had only joined the Bolshevik Party in July 1917, after all, and some “old-Bolsheviks” – those who were Bolshevik members in the long years before and during the First World War – regarded him with suspicion.

The “Troika” scoured through the debates and polemics between Lenin and Trotsky to find any quotes to damage his reputation, even though all such disputes had been rendered entirely academic by Lenin and Trotsky, who were at one on the main issues of the revolution. For example, Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution” (better translated as “continuous” or “uninterrupted revolution”) was used against him, despite the fact that Lenin came to agree with him in 1917, and essentially implemented the theory by pushing for a workers’ revolution in October.

Smears

Trotsky’s popularity led to accusations that he was causing factional disputes just so as to become the sole leader after Lenin, and his respect in the Red Army led to suggestions that he could seize control militarily, like Napoleon Bonaparte after the French revolution. There is no evidence for any of that, but the smears served their purpose. His oratory and sharp mind, meanwhile, led him to be described as arrogant and haughty.

troops during the Civil War

On top of that, both Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, contracted malaria and for long stretches of 1923. So, during this intense faction fight, they were forced to take rest cures and have extended breaks from political activity.

But the main weapon of the Troika, as is often the case with bureaucratic leaderships trying to maintain their position, was to keep up constant demands for “party unity”, as, all the while, they were stealthily using their control of the administration of the party and the state to move against their critics in a naked faction fight.

Trotsky found himself in an uncomfortable position. He was committed to the need to maintain the one-party state during “the period of the dictatorship” of the proletariat, and considered a split in the party to have dangerous consequences for the revolution as a whole. Moreover, he had enthusiastically supported the banning of organised factions back in March 1921, following the defeat of the “Workers’ Opposition” faction of Shlyapnikov and Kollontai, who, consequently, did not support him in his battles with the Troika. Later factions, such as Gavril Myasnikov’s “Workers’ Group”, had been expelled from the Party and Myasnikov had even been arrested and imprisoned in 1923.

Trotsky was, therefore, very sensitive to any accusation of fomenting a split or forming a faction himself, and continually had to swear that he was not doing so. Although recognising the central role of industrial workers in restoring the health of the workers’ state, he could not bring himself to give any support to workers who were striking or protesting against the regime outside the confines of the Communist Party itself.

That is why, in The New Course, he delicately tried to balance between condemning factions on one hand, while campaigning against the leadership on the other. He basically said that factionalism was “a scourge”, but that the overbearing behaviour of the leadership was driving members into silence or forming factions because they could not express their serious questions and doubts any other way.

Democratic structures

Trotsky’s remedy for this crisis was the rejuvenation of the democratic structures of the party, the curtailing of the power of the secretariat, and the active involvement of all members, especially workers and young people, in policy making.

Denying the oft-repeated accusation that factions in the party must represent “alien class forces” in some way, he turned the accusation around, accusing the bureaucrats of being a faction themselves, and asked what “class interest” they represented. It is bureaucratism itself, he said, that is the main threat to party unity. Banning factions was a “dead letter” in isolation from a strong but responsive leadership dealing with the source of the dispute through full democratic discussion.

Importantly, Trotsky made it clear that this problem was not some residual problem from the needs of the Civil War, but had actually got worse since the end of that war, when power had been concentrated in the hands of party secretaries, through the system of party and state promotions, transfers and appointments. He pointed out that, on the contrary, during the war there was more open discussion. He calls for a return to “free and comradely criticism, without fear”.

They later joined the “Joint Opposition” in 1927.

Both were executed after show trials in 1936.

In a phrase which, in hindsight, is utterly chilling, he demanded – “from now on, nobody will terrorise the party.” In truth, how could anyone, in 1923, have imagined the depths of horror and murder to which the Stalinist bureaucracy would sink in the following decades.

Nevertheless, the constant refrain of “party unity” prevented Trotsky from waging all-out war on the leadership. The New Course does not “name names”, and its harsh criticisms are softened by lots of caveats. He did not want to risk being labelled as a splitter from the party that meant everything to him, and his view was that the bureaucracy as a whole was not yet, at that time, beyond redemption. In hindsight, it could be argued that the processes were already too far gone and that the Party was becoming the problem, not the source of the solution.

In the autumn of 1923, a group of prominent Communists, including many of Trotsky’s closest allies, produced the Declaration of the 46, echoing nearly all of Trotsky’s criticisms. However, it also called for an end to the banning of factions. Trotsky did not support this, and in fact, did not sign the document, even though he was severely criticised, in any case, for being ‘behind it’ in some way.

Party unity!

Then the Troika and their allies operated in cynical bad faith, by passing a motion at the Central Committee which appeared, in broad terms, to support his line, but was short on details and did not commit to ending the central control of the secretariat. It also harshly condemned factions. They invited him to sign it, and he did – for the sake of party unity!

Trotsky’s tactic, realising that they would seek to ignore the fine words of the resolution and neuter its implementation, was to enthusiastically welcome the resolution and attempt to hold the leadership to it – to hold their feet to the fire, so to speak.

That is reason for the title of the book – The New Course. Trotsky was polemically trying to force the leaders to implement their own “new course” as they had agreed in the resolution. But they had no intention of doing so, and Trotsky’s arguments were maybe rather too subtle for many party members, who just saw the leaders presenting a façade of unity.

A major hammer blow to Trotsky’s hopes of restoring the inner regime of the Communist Party was, of course, the death of Lenin, on January 21 1924. Instead of Trotsky being able to make use of Lenin’s prestige and respect to help him move against the Troika, Lenin’s death allowed Stalin and the other leaders to associate themselves directly with his memory as Lenin was elevated, against his express wishes, into an almost God-like father of the nation.

Anyone like Trotsky, who had debated and argued with Lenin in good faith, was seen, by definition, as an unreliable and dangerous element. The Troika redoubled their petty slanders about so-called “Trotskyism”, focusing particularly on his theory of “permanent revolution”.

At the 13th Party Congress in May 1924, with many delegates now being hand-picked by the bureaucracy, Trotsky was clearly defeated. Lenin’s now-famous testament, in which he harshly criticises Stalin, was read out but then kept secret and not published. In February of that year the so-called “Lenin levy” had brought in hundreds of thousands of brand new “raw” members who could be manipulated to support the leadership.

This Congress also launched the completely new theory of “Socialism in One Country”, in effect the beginning of a process of placing the purely national interests of Russia (and then the Soviet Union) before the interests of a victory of a workers’ revolution internationally – which Trotsky recognised as the only way that true socialism could be built in the Soviet Union. After the Congress, Stalin even had the nerve to label “Trotskyism” a “petit-bourgeois deviation”!

Just four years later, Trotsky found himself expelled from the party that he had virtually co-led. He was sent into “internal exile” in Kazakhstan in 1928 and deported altogether from the Soviet Union one year later.

He spent the rest of his life building the international Left Opposition to Stalin, as the whole generation of Bolsheviks who led the October Revolution, including Zinoviev and Kamenev themselves, were wiped out – executed on absurd charges of “Trotsky-Fascism”, and hundreds of thousands met their deaths in the Great Terror of the late 1930s.

Notes – The scale of the Stalinist reaction can be seen by the fates of those mentioned in this article.

Lev Trotsky – assassinated by Stalin’s agent (1940).

Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev – both executed after a show trial (1936).

Alexander Shlyapnikov – Charged but did not confess. Executed in 1937.

Gavril Myasnikov – Fled abroad. Lived in France as a factory worker from 1930-1944, during which he was arrested by the Gestapo but escaped. Accepted an invitation to visit the USSR in 1945 (!) where, despite a promise of amnesty, he was arrested and executed.

Alexandra Kollontai – Specialised as a Soviet ambassador to various Scandinavian countries from the 20s to the 50s. Died in 1952, one year before Stalin himself, having miraculously escaped the purges.

Natalia Sedova – Stayed in Mexico and continued to be an active revolutionary. Wrote Trotsky’s biography (with Victor Serge). Died in 1962.

Both of Sedova and Trotsky’s sons, Lev and Sergei, were assassinated by Stalinist agents in the 1930s.