Review by Andy Ford, biomedical scientist

The late Stephen Jay Gould is known for his large output of books on popular science, particularly in regard to evolution. He was the author of The Panda’s Thumb, The Mismeasure of Man, Ever Since Darwin, and many other books. With a co-worker, Niles Eldridge, he developed the theory of ‘punctuated equilibria’, by which they argued that evolution progressed by relatively slow phases (near equilibrium) punctuated by periods of rapid and explosive evolutionary branching (and extinctions).

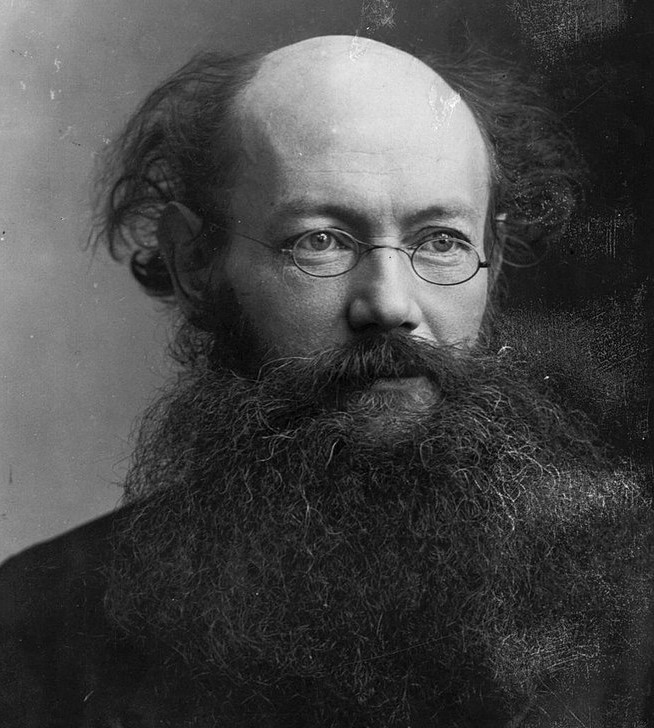

Gould was particularly interested in the idea of so-called ‘Social Darwinism’ and in 1988 he took up the way that Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution were misused. The idea of Social Darwinism is that human society is, and should be, viewed as a battle for existence between people, ‘races’ and and nations, in which the strongest survive at the expense of the weak. Surprisingly, in this 1988 essay, it was to the Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin that he turned.

Gould points out that Darwin did not base his ideas of natural selection and evolution on just a bloody ‘struggle for existence’ where each individual organism was pitted against all the others. The ‘struggle for existence’ was a metaphor to try and put across what ‘survival of the fittest’ meant. Of course, one way for an organism to succeed might be to eliminate all competitors, but as Gould explains, “Co-operation, symbiosis and mutual aid may also secure success in other times and contexts”. In his seminal work, Origin of Species, Darwin said that as well as struggle between individuals, organisms can also be seen to struggle against the environment:

“I use this term [‘struggle for existence’ AF] in a large and metaphorical sense including dependence of one being on another, and including (which is more important) not only the life of the individual, but success in leaving progeny. Two canine animals, in a time of dearth, may be truly said to struggle with each other which shall get food and live.

“But a plant on the edge of a desert is said to struggle for life against the drought…. As the mistletoe is disseminated by birds, its existence depends on birds; and it may metaphorically be said to struggle with other fruit-bearing plants, in order to tempt birds to devour and thus disseminate its seeds rather than those of other plants. In these several senses, which pass into each other, I use for convenience sake the general term of struggle for existence”.

Malthus pointed to an ‘inevitable’ excess of population

But the early critics of Darwin, like Tolstoy and Kropotkin, did have a point. Darwin’s examples mainly illustrated “nature red in tooth and claw” perhaps to lead his public away from the prevailing orthodoxy of a harmonious God-given natural world, and he allowed his later popularisers to stress that aspect of his theory. Darwin, like anyone else, was a man of his time, and his outlook reflected the ideas of the English bourgeois thinker Thomas Malthus.

Malthus saw that population tended to grow geometrically, whereas food supplies, at best, increased arithmetically. From this he drew the dismal conclusion that there would always be an ‘excess of population’ and that some people were destined to die, others to thrive.

Of course, for Malthus those destined to die were ‘paupers’ and their children, and those destined to thrive were the bourgeois – people like himself. Darwin transferred these ideas to the natural world, seeing nature as a sort of fixed space where any new species had to fight for its place, to simply force its way in – or face extinction.

And then Darwin’s chief populariser, Thomas Huxley, went even further in explaining nature as some sort of gladiatorial contest. He went on to transfer these ideas back to human society, in a series of famous essays on ethics, The Struggle for Existence in Human Society (1888), informed by his interpretation of Darwin’s ideas. Left to itself, Huxley said, human society would descend into a struggle “of each against all”. The solution was obvious – to him.

Social Darwinism used to justify racist policies and imperialism

To avoid such a nightmare, society had to be overseen by a wise state, probably staffed by people like Huxley. Later imperialists would extend the concept further – that ‘savage races’ should be controlled and developed by ‘wiser, more advanced’ nations. In this way, Darwin’s ideas were distorted by some into a justification for empire, cultural destruction and even genocide.

Gould differs from Huxley. Whereas Huxley had seen nature, unrestrained, as a brutal struggle, Gould describes nature as “Sometimes nasty, sometimes nice…and really neither, as the human terms are so inappropriate. Nature offers no guide to morality.”

Yet another view is that nature is inherently co-operative. Gould speculates, “Perhaps cooperation and mutual aid are the common results of the struggle for existence”. This brings Gould to the unexpected figure of the revolutionary anarchist Kropotkin. In 1902 Kropotkin penned a response to Huxley, entitled Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution, in which he argued that cooperation was more successful than an individual struggle for existence. Kropotkin then argued that human societies should be built on this natural foundation.

Gould was alerted to Kropotkin’s work on evolution when he read Daniel Todes’ book Darwin’s Malthusian Metaphor and Russian Evolutionary Thought 1859-1917”, which published, in many cases for the first time in English, the rich literature of Russian 19th century biology. Kropotkin’s 1902 book had tried to bring this school of thought into the British debate on evolution and morality. As it did not chime with the highly imperialist views held in early 20th century Britain, his book remained a curiosity without influence.

Russian science had a different empirical background

But the Russian scientists who were Kropotkin’s sources had developed, according to Gould, “A well-developed Russian critique of Darwin, based on interesting reasons and coherent national traditions”.

Gould explains that the Russians rejected “Malthus’s claim that competition, in gladiatorial mode, must dominate in an ever more crowded world where population, growing geometrically, inevitably outstrips and food supply that can only increase arithmetically”. Tolstoy even went as far as to denounce Malthus as a “malicious mediocrity”.

The Russian scientists had a completely different empirical background to Darwin, or his co-thinker Wallace [see article here, on Wallace]. Instead of being brought up in the free market of Victorian England, they could see before them the common landownership and labour of the Russian peasant communities; and instead of doing their fieldwork in the hyper-competitive tropical ecosystems of South America or Indonesia, they had often spent years in the wilds of Siberia, where the main struggle of both plants and animals was not against each other, but against the harsh environment.

Kropotkin himself had spent years in Siberia as a young military officer, but had used much of his time in studies of natural history. He saw a different natural world to that described by Darwin and Wallace:

“Two aspects of animal life impressed me most during the journeys which I made in my youth in Eastern Siberia and Northern Manchuria. One of them was the extreme severity of the struggle for existence which most species of animals have to carry on against an inclement Nature; the enormous destruction of life which periodically results from natural agencies; and the consequent paucity of life over the vast territory which fell under my observation.

“And the other was, that even in those few spots where animal life teemed in abundance, I failed to find – although I was eagerly looking for it – that bitter struggle for the means of existence among animals belonging to the same species, which was considered by most Darwinists (though not always by Darwin himself) as the dominant characteristic of struggle for life, and the main factor of evolution.”

Too much influenced by self-serving bourgeois ideas

Kropotkin could see that Darwin and Wallace, although their theory was a great achievement, had been too much influenced by self-serving bourgeois ideas that justified contemporary capitalist society, and also their experience of the biology of the tropics. One Russian scientist, NI Danielevsky, wrote that the idea of Natural Selection was based on “…a struggle of all against all, now termed the ‘struggle for existence’ – Hobbes’ theory of politics, of competition…Malthus applied the very same principle to the problem of population…Darwin extended both Malthus’ partial theory and the general theory of the political economists to the natural world.”

In place of Darwin’s ‘struggle for existence’ Kropotkin put forward two interlinked drivers of evolution. The first was of organism against organism for limited resources leading to competition; the second was of organism against the environment, leading to co-operation.

In fact, Darwin himself had seen, and mentioned, both forms of struggle, but he had stressed the first as a result of the cultural environment he was working in, and his later disciples one-sidedly promoted the competitive aspect. Even worse, later, less scrupulous scientists and politicians, read the whole thing back into human society. Their writings were full of talk of a “pitiless struggle for existence” and elevated a brutal struggle for survival to a principle of nature and human society.

Of course, it is a lot easier to talk about a “pitiless struggle” when you are not the one who needs the pity or compassion. In practice, these ideas served to justify the most brutal actions of European imperialism, culminating in the regime of the Nazis.

Nazis racist policies towards Eastern European nations

For instance, in 1939, talking about the invasion of Poland, Hitler said, “Our strength lies in our speed and our brutality… I have issued a command—and I will have everyone who utters even a single word of criticism shot—that the aim of the war lies not in reaching particular lines but in the physical annihilation of the enemy. Thus, so far only in the east, I have put my Death’s Head formations at the ready with the command to send every man, woman and child of Polish descent and language to their deaths, pitilessly and remorselessly. . . . Poland will be depopulated and settled with Germans”. The reality is that Hitler was no lunatic outlier beyond the mainstream of European thought. An article in the Guardian in 2004 explained this very well.

On the other hand, Kropotkin wrote that although there is indeed competition and even extermination to be seen in nature, “There is, at the same time as much, or perhaps even more, mutual support, mutual aid and mutual defence…sociability is as much a law of nature as mutual struggle”. He also pointed to social insects like ants, bees and termites, as well as herds and flocks in mammal species, as proof of the success of cooperation.

Kropotkin and the Russian biologists had read their own political and cultural views into nature; but so had Darwin and Huxley. He did sometime veer into what modern biologists term ‘group selection’ – which is a mistaken belief that the unit of evolution can be the group, herd or flock rather than the individual; whereas in fact evolution always operates at the level of the individual organism. However, Kropotkin’s book did grope towards the idea of ‘reciprocal altruism’ which is now a bedrock of modern biology.

All modern human evolutionary theories based on social evolution

Indeed, without exception, all modern theories of human evolution stress the primary significance of social cooperation for the development of modern human beings, in terms of language, tool-making and the capacities of the brain for abstract thought, in a phrase, of ‘cultural evolution’.

Kropotkin’s critique of Darwin, rediscovered and explained by Stephen Jay Gould in 1988, is important. It was a necessary corrective to the crude distortion of Darwinism that Gould says was used to justify “Imperial conquest, racism and oppression of industrial workers as the harsh outcome of natural selection.”

Stephen Jay Gould’s essay, which is worth reading, is called Kropotkin Was No Crackpot, and it can be found here.