By Greg Oxley, La Riposte, France

This is the first part of a two-part article by Greg Oxley, editor of the French marxist newspaper La Riposte. The article analyses the revolutionary events of the 1930s and draws lessons, not just for the working class in France today, but for workers all over the world. Indeed, the article shows the international nature of the workers’ struggle at the time, with the rise of fascism in Europe and also the role of the Stalin bureaucracy in dictating the policy of Communist Parties everywhere.

Part 1 covers the development of the French workers’ parties in the wake of the Russian Revolution and analyses the political zigzags of the Communist Party leadership in that period. This stage culminates with these leaders aligning themselves with the main capitalist party, The Radical Party in a Popular Front in July 1935.

Part 2 will cover the election of the Popular Front government in April/May 1936 and the strike wave that immediately followed, leading to a general strike even before the new parliament had its first sitting. It will cover the subsequent counter-revolution that culminated in the dictatorial pro-Nazi regime of Pétain. And it will draw lessons for today from these events.

**************

The French working class has great revolutionary traditions. In the course of history, French workers have tried many times, with characteristic drive and audacity, to put an end to capitalist exploitation. This was the case during the tragically ill-fated Paris Commune in 1871, then in 1936, in 1944-47 and again in 1968. The lessons of these events are of crucial importance to all those who are engaged in the struggle against capitalism today.

Struggles in France attract worldwide attention

For even today, large-scale struggles in France regularly attract the attention of the workers of the world. The repeated mobilisations of the youth and the French workers’ movement over recent decades suggest that the country is heading towards major class conflict, or more precisely a whole series of conflicts, during which the overthrow of capitalism will ultimately be placed on the agenda as an immediate practical task of the working people. In order to prepare for this challenging perspective, it is necessary to study the past. In this article, we examine the tumultuous events of the 1930s.

The upsurge in militancy which culminated in the general strike of May-June 1936, began in reaction to the anti-parliamentary uprising of the fascist leagues on February 6, 1934. Whither France? and other writings by Trotsky on this period offer a Marxist analysis of exceptional richness and clarity. They show how an historic opportunity to overthrow French capitalism – and in the process deal a devastating blow to fascism in Germany, Italy and Spain – was thrown away by the socialist and communist leaders of the time, with tragic consequences for workers in France and the whole of Europe.

Global economic crisis hits France in the early 1930s

The global economic crisis followed the collapse of the Wall Street Stock Exchange in October 1929 and spread almost immediately to most European countries. However, France was relatively spared until the autumn of 1931. But between 1931 and 1932, industrial production fell sharply by 22%, and stagnated at about the same level until 1940 and beyond.

The industrial crisis hit the working class very hard. The number of unemployed exceeded 350,000 in 1932, rising to 826,000 in 1936. The purchasing power of wages declined. Poverty was spreading in the cities as well as in the countryside. The middle classes (small peasants, small landowners, shopkeepers, etc.), ruined or under threat of it, turned away from the Radical Party – the main party of French capitalism at the time – while the fascist organisations, taking advantage of the impotence of the parliamentary regime, conducted vigorous agitation for the overthrow of the Third Republic.

The Socialist Party (SFIO) in turmoil

At the Socialist Party (SFIO) Congress held in Tours in December 1920, the right wing of the party had been outvoted. Of the party’s 180,000 members at the time of the congress, more than 90,000 had joined since 1918. The new recruits were young, and profoundly affected by the unspeakable horror of the war that had just ended, and implacably hostile towards the “socialist” leaders who had supported the carnage in the name of “Sacred Union”. They were filled with enthusiasm for the Russian Revolution and the Communist International, and were further pushed towards revolutionary ideas by the powerful wave of social unrest that had shaken France in the aftermath of the war.

The party split in two, and the vote in Tours deprived the right wing of the party of something like three quarters of its members, of its financial resources, and also of its newspaper, L’Humanité, which now became the organ of the nascent Communist Party. However, the SFIO retained 55 of the 68 deputies who had been elected to the National Assembly in 1919, as well as almost all the mayors, municipal councillors, and heads of the federations. The SFIO was essentially reduced to a rump of reformist bureaucrats, anxious to maintain their positions, faithful to the “old house”, and supported by a minority and largely demoralised fraction of the membership.

Even after the split, the SFIO experienced a series of internal crises. It was divided between its left wing, hostile to any agreement with the Radical Party, and its right wing, in favour of a coalition government with the Radicals. In 1924, the radical leader Édouard Herriot proposed to include the SFIO in a government coalition. Negotiations between the two parties failed, but the leadership of the SFIO, led by Léon Blum, nevertheless pledged its unreserved support for the Radical government. “We were convinced,” he later wrote, “that we would be of greater assistance to the Radical Party by supporting it from the outside and unanimously than by collaborating with it on behalf of an uncertain and divided party.”

Following Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany, the “neo-socialists” in the SFIO, around Marcel Déat and Adrien Marquet, advocated a policy of “order and authority”, because these slogans, they said, explained the success of the fascists. Later, they themselves became notorious fascists, offering their services to the Nazis during the German occupation in 1940, with Marquet as Minister of Justice and Déat as Minister of Labour. The “neo-socialists” – 22 deputies, 7 senators and some 20,000 members – broke with the SFIO in October 1933. A few months later, the “whip of the counter-revolution” in the shape of the insurrectionary fascist demonstration on February 6, 1934, was to propel the French working class to the forefront of events.

The Communist Party (PCF) and the politics of the “Third Period”

Barely a year after the Nazis came to power in Germany, the demonstration of the armed and growing French fascists sent shockwaves through the French working class. In Germany, the victory of the fascists had been greatly facilitated by the division of the working class. The policy of the so-called “Third Period” – that of the “final collapse of the capitalist order” – decreed by the Stalinist leaders of the Communist International, meant in practice that the German Communist leaders ruled out any joint action between Communist workers and Social Democrats, the latter being qualified as “social fascists”. The policy of leaders of the Communist International prevented any possibility of a fighting agreement between workers’ organisations.

In France, the PCF followed a similar policy until 1934. Since 1924, the party’s policy had been characterised by a series of zigzags, and the policy of the “third period” could only worsen the disorientation of the membership.

In 1929, Trotsky summed up the situation as follows: “The first steps of the party had been full of promise. The leadership of the Communist International then combined revolutionary insight and audacity with the deepest attention to the concrete peculiarities of each country. It was only on this path that success was possible. The changes of leadership in the USSR […] had a pernicious effect on the life of the entire Communist International, including the French party. The continuity of development and experience was automatically broken. Those who led the PCF in Lenin’s time were not only removed from the leadership, but expelled from the party. Only those who showed sufficient readiness to reproduce all the zigzags of the Moscow leadership were admitted to the leadership.”

Socialist Party supporters branded as ‘social fascists’

As a result of the zigzags and expulsions of the late 1920s, the PCF’s membership fell from 83,000 to just to 35,000 in 1929. Then the political mystification on the theme of the “Third Period” and the designation of socialist workers as “social-fascists” isolated the party even more from the mass of workers. In 1931-1932, it had only about 10,000 members. The party was in danger of becoming an impotent sect.

In an article published in La Vérité on November 17, 1933, Trotsky explained how the theory of “social-fascism” had undermined the credibility of the communist movement in the eyes of the workers: “The formula ‘fascism or communism’ is absolutely correct, but only in the final analysis. The fatal policy of the Communist International, supported by the authority of the workers’ state, has not only compromised revolutionary methods, but has given the Social-Democracy, stained with crimes and betrayals, the possibility of raising once again over the working class the banner of bourgeois democracy as the flag of salvation.” […] “Tens of millions of workers are alarmed to the depths of their consciousness by the danger of fascism. Hitler showed them what it means to crush workers’ organisations and elementary democratic rights. The Stalinists have been asserting in recent years that there is no difference between fascism and bourgeois democracy, that fascism and social democracy are twins. The workers of the whole world have been convinced by the tragic German experience of the criminal absurdity of such speeches.”

Abrupt turn in PCF policy in February 1934

Then, from February 1934 onwards, the leaders of the PCF made an abrupt change of orientation. Faced with the mortal threat of fascism, the French working class instinctively yearned for unity in action. During the anti-fascist demonstrations of February 12 in Paris, the demonstration of the Communists merged with that of the Socialists, to cries of “Unity! Unity!” ie with those whom the official “line” of the PCF still described as social-fascists! There was nothing the party leaders could do to prevent this movement of the ranks towards unity. The theory of “social-fascism”, rejected by the rank and file of the communist movement, could no longer be maintained.

However, the sectarian politics of the PCF was replaced, not by a revolutionary united front of workers’ organisations, but by a policy of class collaboration dictated by Moscow, the consequences of which were to prove disastrous for the French working class. Maurice Thorez and the leadership of the PCF advocated a new “sacred union” – renamed the “Popular Front” for the occasion. The Popular Front included not only the Social Democrats, but also the capitalist class, embodied by the Radical Party. Thus, in this latest zigzag, the “social-fascists” and “radical-fascists” of yesterday’s “Third Period” now became vital allies in the struggle against fascism!

Latest turn by Stalin, the logical consequence of ‘socialism in one country’

It should be noted that the abandonment of the theory of “social-fascism” reflected a general turn in the foreign policy of the USSR. From 1924 onwards, Stalin’s rise to power and the subsequent policy changes of the Soviet state, through all their zigzags, were the consequence of the gradual consolidation of the power of a conservative bureaucratic caste. The bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union was essentially the result of the exhaustion and isolation of the revolution in a backward country.

The theory of “socialism in one country”, first mentioned by Stalin in 1924 and then endorsed as the official doctrine of the Communist International in 1928, meant the abandonment of revolutionary internationalism, in favour of a policy dictated by the diplomatic interests of the Soviet bureaucracy. Trotsky said that the adoption of this policy by the Communist International would inevitably lead to the reformist and nationalist degeneration of its national sections. The subsequent course of events, in France as elsewhere, would provide a striking confirmation this prognosis.

Threatened by Hitler’s rise to power and Germany’s rearmament, the Soviet state strove to find points of support among Western European governments, including Britain and France. Stalin reached out to the capitalist parties that advocated “collective security”. In May 1935, the President of the Council, Pierre Laval, went to Moscow and signed a Franco-Soviet assistance pact. In return, Stalin declared that he approved of France’s strategic military policies. Immediately, the PCF ceased all anti-militarist activity and propaganda, adopting the tricolour flag and the Marseillaise.

PCF and SFIO leaders declare support for a pro-capitalist Popular Front

A month later, the PCF leadership declared itself ready to support a capitalist government led by the Radical Party, “provided that it remedies the economic crisis and defends democratic freedoms.” This statement coincided with an appeal to the Radicals by Blum to form “a great popular movement … against the economic, political and social effects of the capitalist crisis.” The Radical Party, devoted body and soul to the interests of the capitalists, was supposedly going to lead the struggle against the “200 families”! The alliance with the Radicals implied the limitation of the Popular Front’s program to superficial reforms, in no way calling into question the fundamental interests of the capitalists.

The PCF, even more than the SFIO, stubbornly refused to include in the Popular Front’s program measures likely to “alienate the Radicals.” Thorez insisted that capitalist ownership of industry and banks had to be scrupulously respected. The alliance with the Radicals was consecrated on July 14, 1935, at the end of a “patriotic” parade through the streets of Paris, where Blum and Thorez marched side by side with the Radical Party leader, Daladier. Significantly, at that time, the Radical Party was still part of the reactionary government of Pierre Laval, which it did not leave until January 1936. Laval was later to take part in Pétain’s pro-Nazi wartime regime, along with Déat and Marquet. He was executed by firing squad in 1945.

**************

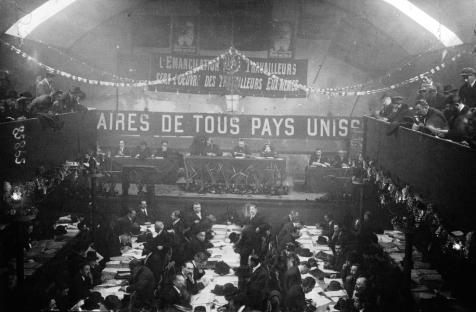

The featured image at the top of the article shows the counter-demonstration of workers on 12 February 1934 against the attempted fascist coup of the 6 February.

Part 2 will cover the election of the Popular Front government in April/May 1936, the strike wave and general strike that followed. It will cover the subsequent counter-revolution that culminated in the dictatorial pro-Nazi regime of Pétain. And it will draw lessons for today from the these events.