Ray Goodspeed provides an overview which sets the scene for the strike that became a defining experience for a generation of socialists and trade unionists. Further articles on the strike will be published by Left Horizons throughout the following year [featured photo – Roar].

………………………….

March 5/6 will be the fortieth anniversary of the start of the titanic battle between the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), together with their families and supporters in the mining communities, against their bosses at the National Coal Board (NCB), the Tory government and the full force of the armed state.

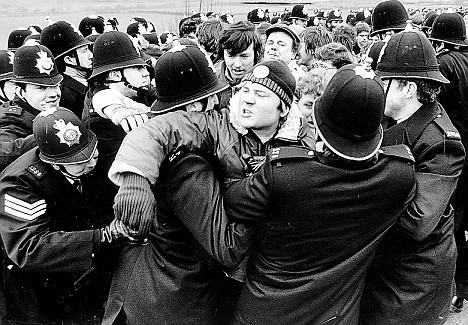

The strike was to last just a few days short of an entire year, during which these communities endured the attempt to starve them back to work, together with unlawful police action, including planned and brutal, violent attacks, most notably at the Orgreave coking plant on June 18, 1984, but also at many other times and places. The strike saw the virtual police occupation of some mining villages, subjecting the residents to random intimidation and violence. They faced an almost uniformly hostile media and, with some notable and proud exceptions, an equally hostile political class, including the gutless, or treacherous, leaders of the Labour Party.

The issue at the heart of the strike was not wages or conditions but a carefully planned strategy of the Tory government under Margaret Thatcher to destroy the NUM, and consequently, to weaken and demoralise the entire organised labour movement. In order to do this, she was quite prepared to simply shut down vast swathes of the mining industry, reducing the often-isolated communities that depended on it to poverty-stricken economic wastelands. The defeat of the miners was, in the end, a crushing blow to socialists and to the Labour and trade union movement, a defeat from which we have only begun to recover over the last few years.

The NUM had not traditionally been a left or radical union since the second world war and it had generally elected “moderate” leaders. But in 1972 and 1974, during a period of great militancy in the trade union movement in general, it had inflicted inspiring defeats on the previous Conservative government of Edward Heath.

In February 1972, the new, young left-wing Yorkshire area secretary, Arthur Scargill had used so-called “flying pickets”, strikers travelling around the country in large numbers, to close down the fuel storage depot at Saltley Gate, Birmingham. The second strike, in 1974, had led to such a political crisis that Heath called a general election on the theme of “who runs the country” – and lost – ushering in a minority Labour government.

Tory Revenge

These victories could never be forgiven or forgotten by the ruling class or its political representatives and they systematically prepared for revenge in the “Ridley Plan” drawn up by a leading Tory of the time.

Under this plan, new laws would be passed to restrict the rights of trade unions; other, weaker groups of workers would be defeated first; the police would be trained and equipped to the level of a para-military force, using much more aggressive and violent tactics; massive stockpiles of coal would be deliberately built up, until the government could provoke a strike at time that suited them best; independent road hauliers would be lined up to transport the coal to minimise the threat of any sympathetic strike by rail workers; and benefits to strikers families would be cut or abolished altogether, to force them back to work.

Thatcher brought in Ian McGregor, a notorious union buster, from the USA and put him in charge of British Steel, where he forced through savage closures and job cuts against a right wing, moderate union leadership. Having done that job well, he was moved to the National Coal Board which, like British Steel, was nominally a publicly-owned industry. Meanwhile in 1981, Arthur Scargill had been elected National President of the NUM, in a huge victory for the left in the union. Some other NUM areas, which had been traditionally dominated by the right wing, also elected left leaders.

The NUM was not in a strong position, despite Scargill’s resolute and charismatic leadership. It had a tradition of strong local organisations based on particular large area coalfields, organised by county, region or nation. Some leading NUM officials in different areas were by no means on the left. Some were vacillating and hesitant at crucial moments and a few were even actively sabotaging the strike from early on. It was even suggested much later that the National Treasurer of the NUM, involved in all major decisions, was working with the security services throughout the strike! He denied this, of course.

Much more important than personalities, however, was a previous decision taken in 1977, under a Labour government (with a well-known left-winger, Tony Benn, as Energy Minister!) to allow a regionally-based wages and bonus scheme, which the national union had strenuously opposed. This ate away at the main strength of the NUM, its famous unity and loyalty. Those regions, particularly in Nottingham and other midland areas, which had more modern equipment and in which the coal was easier to reach, were encouraged to diverge from unity with miners from other areas in pursuit of more money for themselves.

On top of that, miners had worked overtime to produce enormous amounts of coal, which was stored in mountainous heaps by the collieries and in the fuel distribution centres. The miners had literally been sawing off the tree-branch they were sitting on. But in November 1983 an overtime ban had commenced which started to reduce the stockpiles. Many in the union could see what was about to happen to them, but attempts to call industrial action earlier had not been supported widely enough as miners walked into the trap.

Then, in March 1984, in springtime, the worst time of year for a miners’ strike, the NCB (in fact, the Tory government) suddenly announced that twenty mines would close, on the grounds that they were “uneconomic”. The industry had long-established and agreed procedures for deciding whether a mine needed to be closed. Nobody wanted to pointlessly go down a pit which had no more coal.

Secret Plan

But these procedures were torn up, and the financial figures were shamelessly manipulated to give the false impression that these twenty mines had to close. In fact, the secret plan (closely guarded but revealed by documents released decades later) was to close seventy collieries, thereby virtually destroying the industry! Scargill had this information and tried to rally the miners and the wider labour movement on that basis, in the face of repeated denials. Events were to prove him absolutely correct.

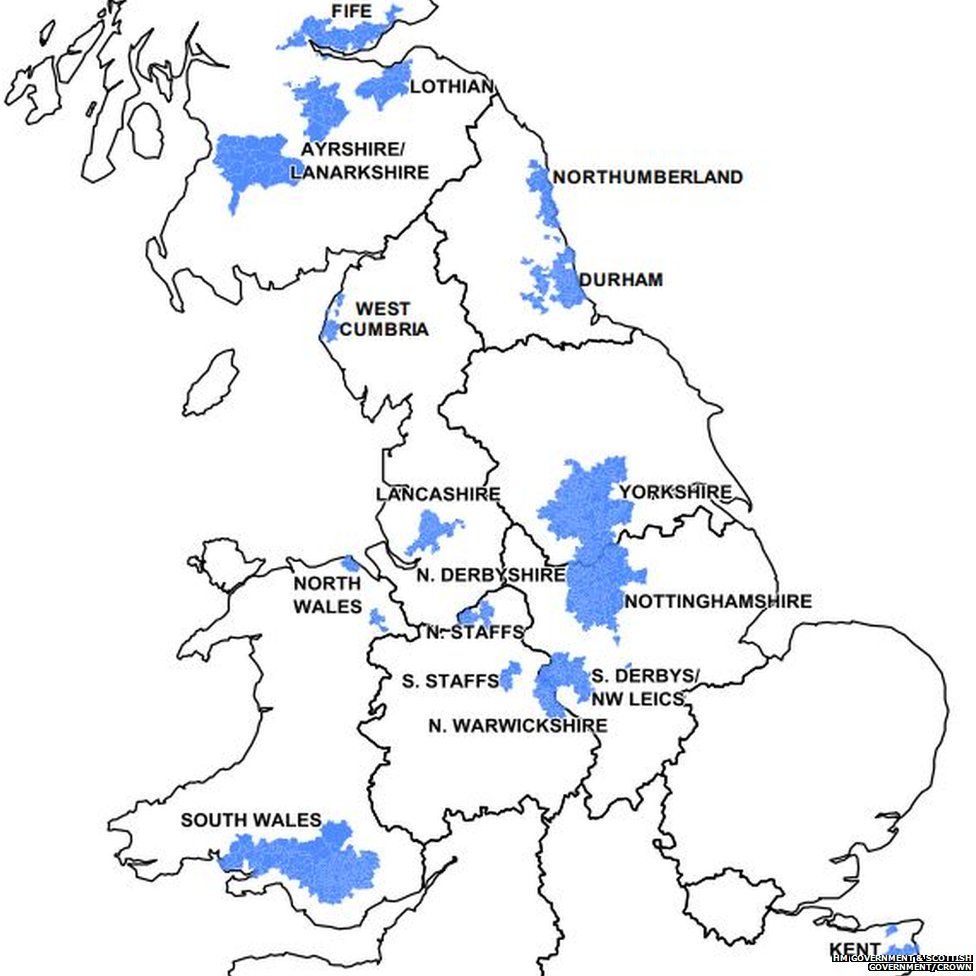

The closure of Cortonwood colliery in Yorkshire in March, finally forced the union to say “enough is enough”. They came out on strike, and called for solidarity from all other miners. The strike spread from area to area throughout the country, particularly in areas such as Yorkshire, Kent, the North-East and South Wales.

However, those less militant areas, especially those in more lucrative and more modern pits were much less enthusiastic, and the area leadership wobbled. The hue and cry went up for a national ballot before any strike could be called, loudly promoted by the media, the Tories and the Labour leaders. Scargill’s position was that it would be wrong for miners in pits not under (immediate) threat to vote away the jobs of those miners who were. He and his supporters were relying on older trade union traditions of solidarity and never crossing a picket line.

Tragically, some areas voted to carry on working and did so for the remainder of the strike, drastically weakening its effects, while the call for a ballot became a central slogan of the NUM’s opponents. Of course, even in Nottingham, Derbyshire and Leicester and other areas, some miners, in the face of victimisation, did obey the strike call, while many around them did not, and they deserve huge respect for doing so.

The atmosphere between those loyal to the NUM and those who went to work became more tense and aggressive as the strike wore on and bitter arguments are still going on to this day, in what are now ex-mining areas. The result of these divisions was that between 20-25 percent of the normal coal output was still produced during the strike. Of course, the pits of those who went to work – the scabs – were nearly all closed after the strike or in the second wave of closures in the early 90s, along with all the rest. They gained nothing from their short-sightedness and disloyalty.

After the strike, in December 1985, the split was made permanent by the formation of a breakaway Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM), organised and funded by shadowy figures acting secretly for the government (as later documents revealed).

Successful pickets

But In the first few days after the strike began, groups of pickets from the more active areas, such as Yorkshire, were quite successful in persuading working miners in the neighbouring area of Nottinghamshire to join them. This was dressed up by the media and the government as intimidation and “mob rule”, though it generally involved relatively small numbers of pickets patiently explaining the issues.

The response of the government was effectively to seal off Nottingham, arresting and even attacking miners who tried to cross the county boundary or were even suspected of trying to do so. The police exceeded their powers and openly flouted the law as they treated striking miners as, in Thatcher’s words “the enemy within”. Huge numbers of police were used to lock down the pit villages and make reasonable picketing activity impossible, or even dangerous. In March, in the midst of violent scenes involving strikers, scabs and police in Ollerton in Nottinghamshire, one young striker from Yorkshire, David Jones, was killed. The killer was never found.

Though the strike was obviously a time of suffering and self-sacrifice in mining communities, it was also a time of determination, heroism, and effective, working-class self-organisation. Women, in particular, organised themselves and their communities more than ever before, starting out with soup-kitchens and food-parcel deliveries, but soon moving on to playing a full part in strike planning, public speaking and picketing. The Women Against Pit Closures (WAPC) organisation permanently changed the lives of the women involved, and changed their role in their communities and in wider society.

It was also a time of inspiring levels of public support. The strike was extremely polarising. For the course of the year you either supported the miners or you didn’t. The two sides were very clearly demarcated. Collections were to be seen on street corners the length and breadth of the country, as well as in workplaces and trade union branches, and even outside football grounds. Money was raised by some churches, mosques and temples and the black and Asian communities were part of the solidarity effort. The lesbian and gay community were also involved in providing money to prevent the Tories from starving the miners back to work.

Firm and long-lasting links were built with so many different sections of working people and with others who simply saw the justice of the miners’ cause and were appalled by their treatment. People also looked to the miners to lead the fightback against all of the appalling attacks that Thatcher had unleashed against them, and there was a general recognition that ”if the miners lose, we all lose”. Food, clothing and other essentials poured in from all over the country and all over the world, sent by working people who were following the strike with close interest. There was an unprecedented level of international solidarity.

Euphoria and despair

It is not possible in one article to deal with the whole history of the strike in detail and so many aspects of the struggle are worthy of separate articles in themselves. There were several highs and lows, with their accompanying euphoria and despair, as the miners sensed that victory was possible, only for it to be snatched away.

[photo Martin Shakeshaft]

By 3 March 1985, after a cold winter of increasing hardship and demoralisation, and after some miners began to drift back to work, the NUM called off the strike, with no concessions and no guarantees for sacked or victimised miners. Some areas, such as Kent, still tried to go it alone for a couple of weeks, but the cold fact was that the miners had suffered a crushing defeat, one that would have implications far beyond the mining industry and for the entire labour and trade union movement.

The question must be asked, “Was defeat inevitable?” The answer is categorically, “No!” It is certainly true that the strike was forced on the union at a time of the government’s own choosing, in spring, with coal stocks piled high. The government planning was thorough, ruthless and effective. The divisions in the NUM and the widespread scabbing represented a serious blow and made winning the dispute immeasurably harder. The financial support for the miners was truly extraordinary and allowed them to continue much longer than they would otherwise have been able to do, yet financial support was never enough to win the strike on its own.

But victory would have been possible if just one other important union, such as steel workers, dockers or rail workers had come out on strike, either in solidarity or in pursuit of their own industrial issues. The different union leaders at the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) in the autumn of 1984 were generous with their warm words, but the desperate need was not for words but for solidarity industrial action.

Then again, even in the absence of such action, the trade union of the colliery deputies (supervisors), NACODS, voted to strike by 82.5 percent October 1984. As it was impossible to open a pit without such supervisory and safety staff, a strike by them would have shut every pit in the country, including those in the midlands, and victory would have been virtually assured. But a shabby deal was cooked up by the leaders of that union in negotiations at the TUC’s Congress House, and their strike called off, leaving the striking mining communities cold, hungry and desperate for another four months before the strike was ended.

Both the stirring inspiration of the miners’ strike, and the terrible consequences of its defeat can barely be exaggerated. But the struggle continues. Today it is clearer than ever, even more than it was in the 1980s under Thatcher, that capitalism can never guarantee adequate living conditions for the majority of working people. They will be forced to fight again and again because they simply have no choice. In those fights we will have to draw on inspirational past struggles but also learn lessons of bitter past defeats.

NB – This article was edited on 7 March to clarify that an overtime ban had commenced in November 1983.