By Michael Roberts

This blog was originally published by Michael Roberts on Sunday, 10 March 2024. The original article can be found here.

**************

Portugal has a general election today, only two years from the last one. It’s taking place early because the Socialist prime minister Costa was forced to call it after a serious of corruption scandals concerning government ministers. Also a Lisbon court recently decided that a former Socialist prime minister should stand trial for corruption. Prosecutors allege that José Sócrates, prime minister between 2005-2011, pocketed around 34 million euros ($36.7 million) during his time in power from graft, fraud and money laundering.

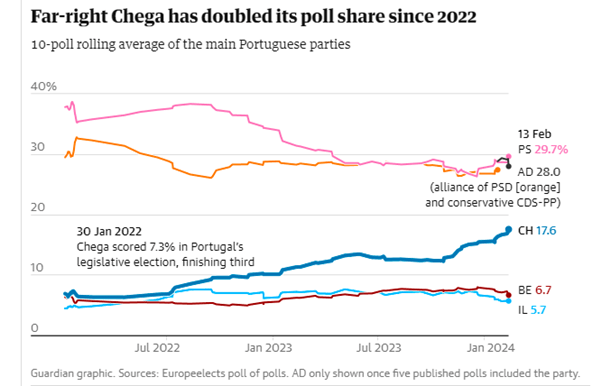

Poll shares of the parties leading up to the election

Just under 11m Portuguese are eligible to vote and the opinion polls suggest that the anti-immigrant, neo-fascist Chega (Enough!) could make the biggest gains and hold the balance of power in parliament between the currently governing centre-left Socialists and the centre-right Social Democrats.

The main opposition to the current government, the Social Democratic Party (PSD), has formed an alliance with the Popular Party (CDS-PP) and the Monarchist Popular Party (PPM), to form what they call the Democratic Alliance (AD) to be led by Luís Montenegro, the PSD leader. But the PSD too is tainted by corruption allegations. A graft investigation in Portugal’s Madeira Islands triggered the resignation of two prominent PSD officials.

What the competing parties offered the electorate

The incumbent Socialists now have Pedro Santos as their leader. The party is offering a few minimal reforms: it intends to return 50% of VAT to those who buy hybrid or electric cars, create an entity that monitors the rental of properties and guarantee public bank financing for those who buy a house, up to the age of 40 – housing is a big issue.

The new AD centre-right alliance purports to defend ‘liberal conservatism’, ‘Christian democracy’ and ‘economic liberalism’. AD states that it wants to implement a maximum tax rate of 15% for people up to 35 years of age, as well 100% mortgages for first-time home buyers.

The anti-immigrant neo-fascist Chega led by Andre Ventura wants to defend ‘national values’ and to curb ‘Islamic fundamentalism’. Chega intends to equate the minimum pension to the National Minimum Wage and provide one year of paternity and maternity leave, shared between the child’s parents.

There are also various small left-wing parties that could poll about 5% between them.

Deregulation distorts the housing market beyond recognition

The pandemic was a disaster for an already weak Portuguese economy. And since then the post-COVID economic recovery has been fuelled by deregulation and a series of schemes designed to lure foreign investment. This has distorted the housing market beyond all recognition in a place where the monthly minimum wage is €760 and where 50% of people earn less than €1,000 a month. The liberalisation of the rental market, the issuing of “golden visas” that confer residence permits in exchange for buying properties worth €500,000 or more, the introduction of tax-saving “non-habitual residency scheme” for foreigners, and, most recently, the creation of a digital nomad visa to allow well-off foreigners to work remotely and pay a tax rate of just 20% have all played a part.

So too – perhaps most obviously – has the snapping up of flats to be converted into lucrative short-term rentals. Now there are 48,000 homes standing empty in Lisbon alone and 750,000 across Portugal as a whole. Portuguese citizens have been driven out of the housing market and there are few state schemes for rental housing. The reality is that successive governments have done nothing about the housing crisis, persistent low pay levels and unreliable public health services.

Sixth lowest average salary in the OECD

Average pay is just 1,300 euros (1,466 US dollars) a month. Among all OECD countries, Portugal has the sixth-lowest average salary but has seen the highest rise in house prices. In 2022, the take-home pay of an average single worker, after tax and benefits, was 71.9% of their gross wage, compared with the OECD average of 75.4%. An average married worker with two children in Portugal had a take-home pay, after tax and family benefits, of 84.6% of their gross wage, compared to 85.9% for the OECD average.

Inequality of incomes and wealth and levels of poverty in Portugal are among the highest in Europe. According to the World Inequality Database, the premier research body for measuring the inequality of incomes and wealth in a country, in Portugal in 2022, the top 10% of adults had 36% of total personal income in the country (before tax and benefits) while the bottom 50% of adults had to share just 19%. The very top 1% have 10% of all personal income. These ratios have worsened under successive governments in the 21st century.

It’s even more unequal when it comes to personal wealth ie property, savings and financial assets like shares and bonds. In 2022, the top 10% of adults had 60% of all personal wealth in Portugal, while the bottom 50% had only 3.6% between them! In other words, they own very little or nothing. The very top 1% had 25% of all personal wealth. And these ratios have worsened in the last 25 years under successive governments.

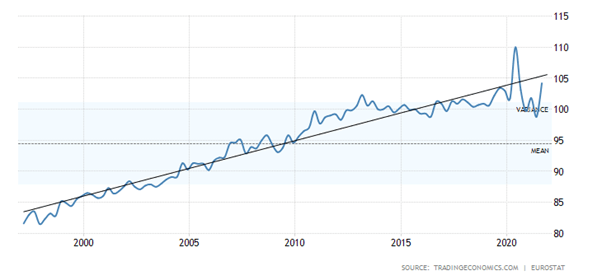

The Costa government came to power pledged to reverse the post 2008 slump austerity policies imposed by the Eurozone. But like other governments in southern Europe in the last decade, it made little progress on growth, productivity and investment, even if it avoided even worse austerity measures. Productivity has been flat for the last eight years.

Productivity level (index = 100)

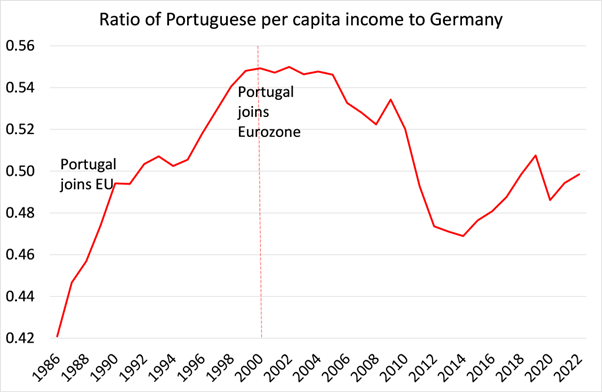

Portugal’s economy has been falling behind the rest of the EU since 2000. The European Union supposedly aimed to ‘level up’ the weaker capitalist economies with the richer core. The opening of trade and investment after Portugal became a member in 1986 appeared to work, as it did for other weaker EU countries. But the introduction of the euro changed all that. Whereas before the weaker EU countries could let their currencies depreciate against the deutschemark to try and remain competitive. That was no longer an option in the Eurozone. Without higher investment and productivity, the weaker capitalist members could not compete. Convergence turned into divergence. Portugal like other weaker members was reliant on foreign direct investment (FDI) from Germany and France. External debt rose sharply and the Euro debt crisis in 2012 in the wake of the global financial crash pushed the country into penury and austerity. Portugal’s GDP per person remains less than half that of Germany.

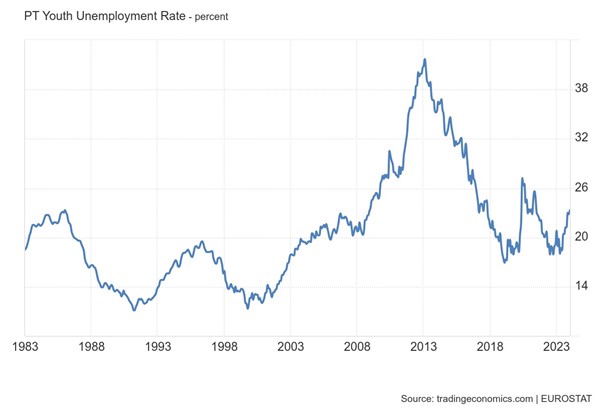

Meanwhile low wages and high unemployment have spurred emigration. Over the past decade – a period that includes governments run by both the Socialists and the ‘centre-right’ Social Democrats – some 20,000 Portuguese nurses have gone to work abroad, in an unprecedented drain of medical talent. The youth unemployment rate is still near 25%.

Youth unemployment rate (%)

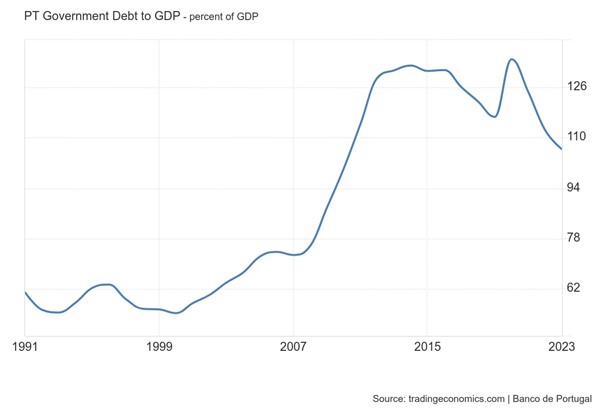

The main parties are putting all their hopes in the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Plan, which pools funds from the richer members to help out the weaker economies – the first time such a fiscal package has been employed across the EU. But the EU money has still not been disbursed. And it comes with strings: namely that the government is supposed to maintain a tight fiscal policy and keep budget deficits down and above all start to reduce its huge public debt ratio.

Public debt to GDP (%)

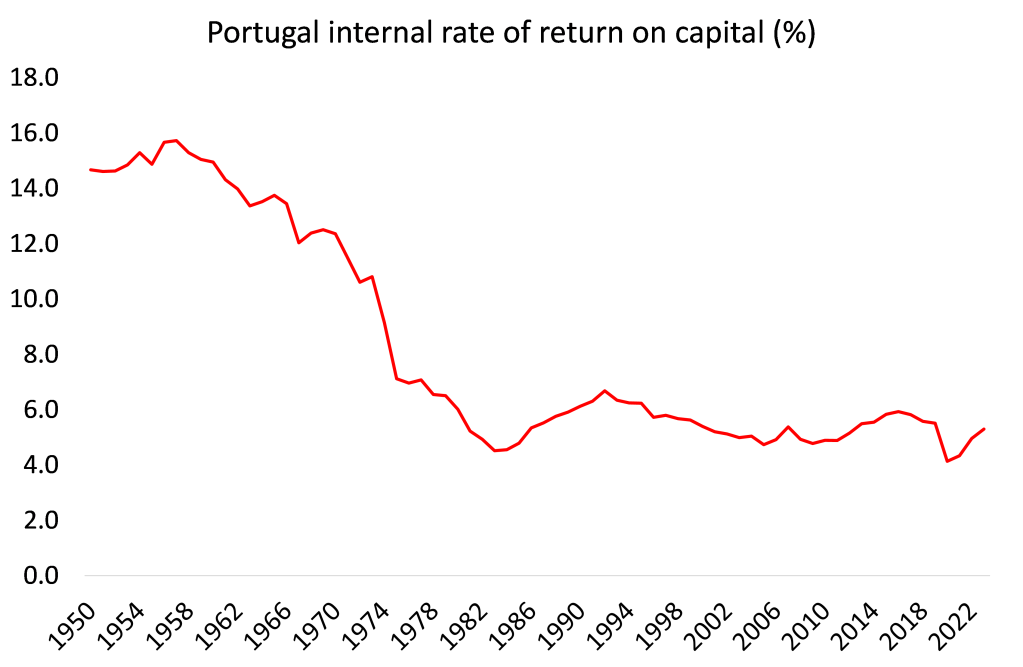

Even though the next government will be getting these funds from the EU to spend on infrastructure and services, it is likely to do little to get a very weak capitalist sector to invest, expand employment and raise wages. That’s because the profitability of capital in Portugal is miserable. It has been flat and low for 40 years. The EU has done nothing for Portuguese capital up to now.

Whoever triumphs in today’s election has no real plan to change the dismal fortunes of Portuguese households. Desperation could see the rise of the neo-fascist right.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.

The featured image at the top of the article shows Luís Montenegro, President of the Social Democratic Party and leader of the political coalition, the Democratic Alliance.