By Michael Roberts

Current IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva is seeking a second five-year term as IMF managing director after being nominated by a string of European countries to lead the institution. In doing so, she recently delivered a number of speeches outlining what she sees the IMF will be trying to achieve over the rest of this decade.

She said the major economies are experiencing slowing and low real GDP growth and, according to her, the reason for this is soaring inequality of wealth and income. “We have an obligation to correct what has been most seriously wrong over the last 100 years – the persistence of high economic inequality. IMF research shows that lower income inequality can be associated with higher and more durable growth,” she said.

IMF admits that inequality has a negative impact on growth

It’s a new argument. Until recently, the IMF reckoned faster growth depended on higher productivity, free flows of capital, globalization of international trade and ‘liberalisation’ of markets, including labour markets (meaning weakening labour rights and unions). Inequality did not come into it. This was the neo-liberal formula for economic growth. But the experience of the Great Recession on 2008-9 and pandemic slump of 2020 seems to have delivered a sobering lesson to the IMF’s economic hierarchy.

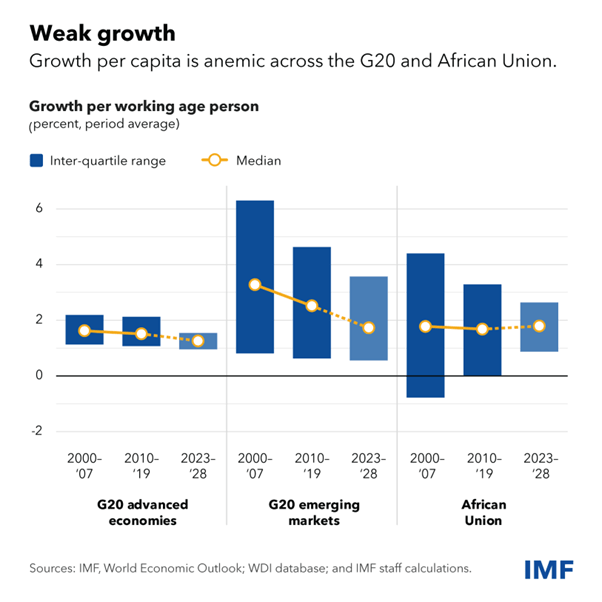

Now the world economy is suffering from “anemic growth”.

And globalisation is fragmenting along geopolitical lines—around 3,000 trade-restricting measures were imposed in 2023, nearly three times the number in 2019. Georgieva is worried: “Geoeconomic fragmentation is deepening as countries shift trade and capital flows. Climate risks are increasing and already affecting economic performance, from agricultural productivity to the reliability of transportation and the availability and cost of insurance. These risks may hold back regions with the most demographic potential, such as sub-Saharan Africa.”

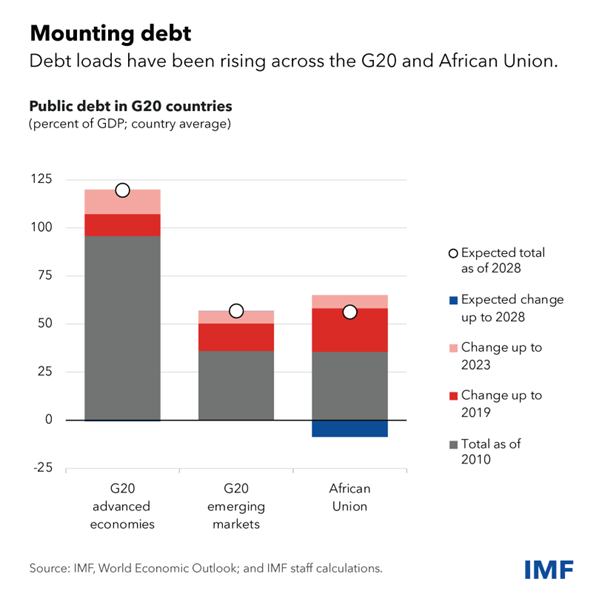

Mounting debt

Meanwhile, higher interest rates and debt-servicing costs are straining government budgets—leaving less room for countries to provide essential services and invest in people and infrastructure.

So Georgieva wants a new approach for her next five-year term. “With recent improvement to the global-near term outlook, G20 policymakers have an opportunity to rebuild policy momentum, setting their sights on a more equitable, prosperous, sustainable and cooperative future.” The previous neoliberal model for growth and prosperity must be replaced with ‘inclusive growth’ that aims to reduce inequalities and not just boost real GDP. The key issues now should “inclusion, sustainability, and global governance, with a welcome emphasis on eradicating poverty and hunger.”

Georgieva refers us back to Keynes

The talk about ‘inclusive growth’ is not new, but it is from the IMF. How is this to be done? Here Georgieva refers us to the supposed solutions apparently provided by John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression of the 1930s, in particular Keynes’ seminal essay Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.

Let me remind readers that Keynes’ essay was originally based on a speech he made to students at King’s College, Cambridge in the depth of the 1930s depression. Keynes was very worried that his students were being attracted towards Marxist alternatives to the capitalist crisis. He saw the need to stop that by showing the capitalism would get out of its current mess and eventually deliver prosperity for all.

Georgieva argued that Keynes had been right to predict that technology gains would deliver an eightfold increase in living standards in 100 years’ time from 1931. Georgieva took this up and said the target for the IMF (over the next 100 years!) was to do the same ie. achieve an average nine-fold increase in living standards for 8bn plus people on the planet. But, says Georgieva, it can’t be done “unless we foster a fairer global economy.”

Economic growth and inequality since the 1930s

On the Keynes’ prediction for growth since the 1930s, Georgieva was not entirely accurate. Global per capita real GDP was $1,958 in 1940 and reached $7,614 in 2008. Given recent slow growth, average global per capita GDP could reach $11,770 in 2030. But that’s a rise of only six times from the 1930s.

In her speech Georgieva admitted that “He [Keynes] was also too optimistic about how the benefits of growth would be shared. Economic inequality remains too high, within and across countries”. You don’t say! It was not that Keynes was too optimistic. He ignored completely the issue of inequality that Georgieva now wants to take up. He assumed that the major capitalist economies were equivalent to the world economy. And he made no distinction between the imperialist core and the poor periphery or between rich and poor inside a country. He did not refer to inequality at all – for him (mean) average growth was enough.

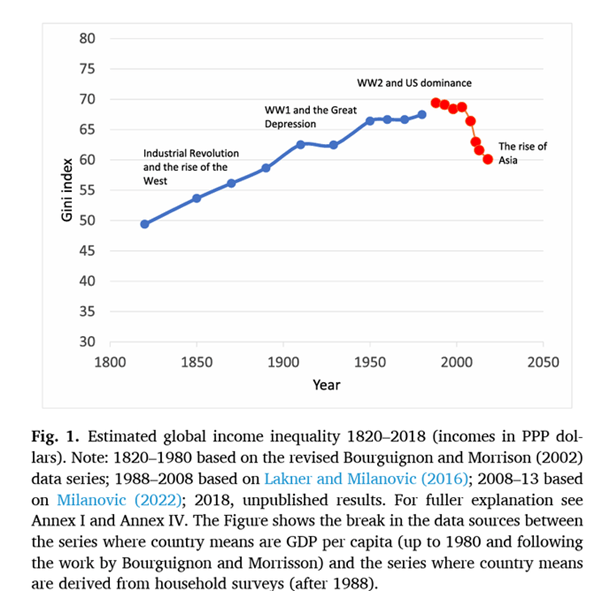

And what has happened to the inequality of global incomes since Keynes’ address? Just look at the latest analysis by global inequality expert, Branco Milanovic, in a new paper.

The global inequality index (Gini) has risen from around 50 in the early 19th century to about 66 in the 1930s, then hitting near 70 by the end of the 20th century. It has only fallen back since because of the rise of China, where over 900m Chinese have been taken out of World Bank defined poverty levels. The World Inequality Report (WIR) 2022 shows that after three decades of trade and financial globalisation, global inequalities remain extremely pronounced… “about as great today as they were at the peak of Western imperialism in the early 20th century.” (when Keynes did his address). Georgieva is arguing that prosperity and better living standards are only possible now by reducing inequality. But it appears that Keynes does not offer Georgieva any guidance on this at all.

So what do the IMF economists and Georgieva say needs to be done to reduce inequality? They do not propose a wealth tax on billionaires; they do not propose any effective measures to end tax havens for the super-rich and big corporations. Their only measure, it seems to me, is to back the recent vague agreement made to have a minimum corporate profits tax globally (with many attending loopholes). And they suggest higher tax rates at the top of the income distribution, the introduction of a universal basic income, and increased public spending on education and health.

As I mentioned in a previous post, leading inequality economist, Gabriel Zucman was invited to address the G20 finance ministers meeting in Brazil and asked to come up with detailed measures to tax the super-rich. Zucman admitted that “it may take years to get there for the super-rich” What is the likelihood that the G20 governments will agree to any measures against billionaires or tax havens?

Pre-distributive measures versus post-distributive measures

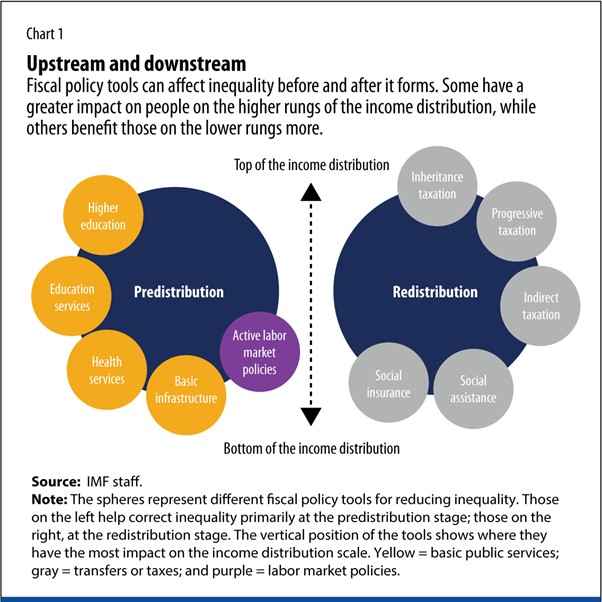

And anyway, as I argued in that post, all these tax measures are redistributive; ie they do not deal with the causes of inequality in the first place; they just aim at some redistribution afterwards. It’s like taking medicine that may take away some of your headache, but does nothing to stop the causes of the flu that keeps infecting you.

The IMF’s economists have recognised the distinction between pre-distributive measures to reduce inequality (of income only) and redistributive. But their suggested pre-distributive policies refer only to incomes and fail to address the economic structure of wealth inequality that in the past I have argued is key. Moreover, can they really expect education, health and infrastructure spending to be ramped up across a world economy as it currently operates?

Indeed, the leading inequality economists, Piketty, Saez and Zucman, recently concluded that “Given the massive changes in the pre-tax distribution of national income since 1980, there are clear limits to what redistributive policies can achieve.” That’s why these days, Piketty advocates going ‘beyond capitalism’ to break the back of inequality of income and wealth which, in my opinion is endemic to a social system where a small group of people own all the means of production and through banks and companies squeeze every last cent they can out of the rest of us.

Rivalry between the major economic powers is growing

Georgieva concludes that “In the years ahead, global cooperation will be essential to manage geoeconomic fragmentation and reinvigorate trade, maximize the potential of AI without widening inequality, prevent bottlenecks on debt, and respond to climate change.” Global cooperation? We are in a world where rivalry between the major economic powers is intensifying, with the US imposing trade tariffs, technology bans, and military measures against China, while Europe conducts a proxy war with Russia.

Highlighting Keynes’s maxim that “in the long run, we are all dead” in her speech, she said “He meant the following: instead of waiting for market forces to fix things over the long run, policymakers should try to resolve problems in the short run,” she said. “And it’s a call to which I for one am determined to respond – to do my part for my grandchildren’s better future. Because, as Keynes put it in 1942: ‘In the long run almost anything is possible.’” Well, yes, in the long run, ‘almost anything is possible’ but not necessarily for the betterment of humanity or the planet.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.