Andy Ford (Warrington South Labour member) looks at the relationship between the Communist Party and the Labour Party in the 1920s. Part one deals with the period up to 1926. Look out for part two (here) covering 1926-31. [Photo – float from 1928 showing the complete integration of the Communists into the Labour Party]

******

The recent byelection win for George Galloway in Rochdale has once again led to excited chatter about ‘a new worker’s party’ and an electoral challenge to Starmer’s uninspiring, corrupt party. In these times it is worth looking back at the history of the Labour Party and the repeated proclamations by sincere but impatient socialists that the Labour Party is “finished”, and “needs to be replaced”.

In the 1920s the right-wing, middle-class wing of the Labour Party rose to dominance after the defeat of the General Strike and the failure of the first Labour government of 1924. At the same time they faced a powerful left wing, rooted in the unions and Labour Party, stiffened by the presence of thousands of communists in their ranks. It was a conflict that played out across the four years 1924-1928. It unfortunately ended with the Communist Party walking away to make a ‘bold stand for socialism’, leaving the right wing in charge. As for the Communist Party, their membership more than halved, to 2,350 by 1930.

The Labour Party emerged from the First World War immeasurably strengthened. Their vote climbed from just 400,000 in 1911, to 2.5 million in Lloyd George’s ‘khaki election’ of 1918, and to 4.35 million in 1923. In industry the working class had been reconstituted in the war years, and in 1919 there had been an almost insurrectionary wave across Britain with strikes – even a strike of police – workers’ demonstrations, battleships in the Mersey and tanks deployed in Glasgow.

These events pushed the Labour Party far to the left. Their programme “Labour and the New Social Order” promised to fully reconstruct society along socialist lines and to nationalise the land, the mines, railways, power companies and docks. But British capitalism was in decline, despite its gigantic empire, and the ruling class knew it; at some point they were going to have to ‘deal with’ their own working class. They began to prepare both the mailed fist – and the velvet glove.

Communist Party founded – 1920

In this ferment the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was founded in 1920. It was founded from a fusion of a whole number of diverse, small socialist groups – the British Socialist Party, the Socialist Labour Party and the South Wales Socialist Societies, and others. In 1921 the party assimilated Sylvia Pankhurst’s Workers Dreadnought group and many of the best elements of Red Clydeside. They even had one MP, the eccentric ex-military officer Colonel Cecil L’Estrange Malone, who had been elected on a Liberal Party ticket for East Leyton in 1918, but later joined the British Socialist Party after travelling to Russia.

The trouble was that some of these groups had diametrically opposite views on key questions of the day, including the Labour Party. The British Socialist Party had been a Labour Party affiliate since 1916. So when Cecil Malone joined it, he became a Labour MP at the same time. But on the other hand, the Socialist Labour Party believed the Labour Party was a reformist stooge of the elite and an “obstacle to socialism”.

Published in 1920

It was to address these ultra-left tendencies that Lenin wrote “Left Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder” in which he recommended the young Communist Party to join the Labour Party, and to strive for full affiliation, in order to be part of the actual working-class movement, and then to seek to attract and influence its best elements.

In the early 1920s, of 6,000 CBGB members, around 3,000 were in the Labour Party. In the 1922 election the Party won two MPs standing as official Labour Party candidates – Shapurji Saklatvala in Battersea North and Walton Newbold in Motherwell. However the Labour Party rejected the affiliation of the Communist Party in both 1920 and 1921 and this strengthened the hand of those in the CPGB who argued that within the Labour Party the Marxists were “subordinated to the point of elimination” and in danger of merging with it.

Nevertheless up to 1923 the CPGB maintained a broadly correct orientation to the Labour Party, warning of future betrayals by the leaders and urging the rank and file to insist on a socialist programme for Labour.

Labour minority government

In the December 1923 election the Labour Party got 4.3 million votes and 191 seats, to the Tories’ 5.3 million and 258 seats. The Liberals, under Asquith came third with 158. It was here that the ruling class deployed their ‘velvet glove’. The Conservative leader, Baldwin, went to the King, urging him to set a trap for the Labour Party – to allow them into government, but as a minority administration. “After all”, said the Liberal leader, Asquith, “If a Labour government is ever to be tried in this country, as it will be sooner or later, it could hardly be tried under safer conditions”.

George V obliged, and sent for Ramsey MacDonald to form the first Labour government. The whole of the ruling class – Conservative, Liberal, and the Monarchy, worked together to ensnare the Labour leaders.

And it worked. MacDonald began by bringing in barristers and Conservatives into his cabinet as part of a ‘broad church’ but passing over key left-wing MPs. Once in office the wealth tax was abandoned and the corporate levy on excessive profits was abolished.

The moment of truth came when the government proposed the annual Armed Forces Bill. Up till then, the Labour Party had always put an amendment that soldiers should have the right to refuse duty against strikes and strikers. But that year MacDonald’s government proposed the Bill, George Lansbury moved the usual amendment, but then to the shock and disgust of the Labour and trade union rank and file, MacDonald whipped his MPs to vote with the Tories and Liberals and pass the Bill unamended. This at a time when soldiers were being constantly deployed to face down strikes and even to do the strikers work. There was a huge kickback in the unions and Labour Party membership.

Then Leader of “National” Government ( 1931-35)

The Communist Party was the backbone of the opposition to the leadership’s retreat from the socialist policies they were elected on – much to MacDonald’s anger. He then authorised the arrest of J.R. Campbell, editor of the Communist journal, Communist Workers Weekly, under the Mutiny Act of 1797. That only increased working-class fury – and the influence of the Communist Party. MacDonald, foolishly, decided to make the Campbell prosecution a matter of confidence, and in October 1924 his government fell after less than a year.

But now the Labour leaders and the ruling class knew their enemy. They were determined to separate the Marxists from the Labour Party ranks. This was not an easy task.

After MacDonald’s Fiasco – calls for socialist policies

After the fiasco of Ramsey MacDonald’s minority government the 1924 Labour Party conference was flooded with resolutions calling for socialist policies, and control of the membership over their leaders. Members wanted conference to determine the policies to be followed by the Party in government, and the cabinet to be elected by the PLP, not appointed by the Prime Minister. The Communists even had around 30 delegates to the 1924 conference.

Nevertheless the leadership, with the help of the right-wing union leaders, managed to pass a motion that Communists in future could not be accepted as Labour Party candidates and that membership of the CPGB was incompatible with membership of the Labour Party. But this second proposal was only passed by 1,804,000 to 1, 546,000 votes, with a stipulation that the issue be revisited at the 1925 conference.

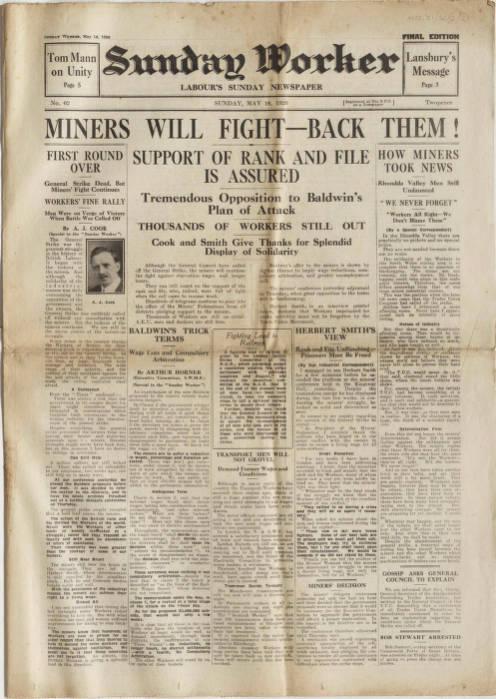

The CPGB sought to capitalise on the influence gained in the Labour Party. In January 1925 they decided to launch an organisation to “Develop, organise and strengthen…the left wing…both in the Labour Party and the trade unions”. In March 1925 the CPGB launched a weekly newspaper, the Sunday Worker. Although it was financed by the Communist International, to the tune of £20,000 (over £1 million in today’s money), and the editor was a Communist, it aimed to be a far broader paper, and threw its pages open to left wing writers and politicians of all kinds. It soon attracted a readership of around 100,000.

At the 1925 conference, the exclusion of Communists from membership of the Labour Party was passed by 2,870,000 to 321,000 votes, but it was not as clear cut as those numbers make it appear. In the Miners Union delegation, the decision to vote for exclusion was carried by only 67 votes to 56; half of the AEU delegation of 35 voted against exclusion. Within the Independent Labour Party, their delegation of 24 was split 13-11 for exclusion. However, exclusion was carried. MacDonald had got his way.

The Communist press noted the fact that at the crucial moment the ‘lefts’ had ducked and not stood up to MacDonald and the right wing. Harry Pollitt wrote, “The left wing were scared stiff and allowed MacDonald to ride roughshod over them…” – leaving the CPGB isolated. William Paul, the communist editor of the Sunday Worker criticised the left leaders who “got cold feet and ran away when things got serious”. He said that the left MPs used “bold phrases in their constituencies” but would not, or could not, organise in the Labour Party for socialist policies.

The CPGB set out to remedy the left’s failing. They convened a London Left Wing conference in November 1925, chaired by Joe Vaughan, the Communist mayor of Bethnal Green, and addressed by the miner’s leader A.J. Cook and Alex Gossip of the Furniture Makers union.

National Left Wing Movement

The first National Left Wing Movement (NLWM) conference was held in September 1926 in Poplar, East London. The conference drew together official delegates sent by 52 Divisional and Borough Labour Parties, and a further 40 groups from constituencies where the left was a minority. The aim was to fight the expulsions and to take the necessary steps to win the Labour Party to socialist policies.

Joe Vaughan clearly stated that there was no aim to move towards a new party to compete with Labour and the conference adopted an excellent socialist programme – against wars, militarism, imperialism and monarchism, and for nationalisation without compensation, a 44-hour week, minimum wage of £4 a week, relations with the USSR, full female suffrage, political rights for soldiers, police and civil servants, and abolition of the monarchy and House of Lords.

But 4 months earlier, in May 1926 the General Strike had gone down to defeat. The ruling class had used their ‘mailed fist’ and had precipitated their confrontation with the working class, and thanks to the treachery of the Labour right, and the vacillation – and ultimate betrayal – of the lefts, including the left trade union leaders, they had won. Trotsky analysed these processes in “The Anglo-Russian Committee and Comintern Policy” (1926). The left leaders; actions were characterised by weakness, vacillation, and ultimately surrender to the right wing.

For instance even ‘Red Clydesider’, James Maxton said that “Much as we dislike disaffiliations…where the Liverpool decision [to expel communists] is contravened there is no choice but to expel”. In other words, we disagree with expulsions, but we respect the right of the bureaucracy to do so!

And in June 1926 the ex-Poplar councillor George Lansbury said that he would “abide by the majority decisions on the question of Communist expulsion” but by October he was declaring of the Communists, “They’ve been to prison with us! When you tell us to turn them out – we won’t”.

The left leaders were totally inconsistent, bending with whatever pressures were brought to bear on them.

Look out for Part Two (1926-1931) here…