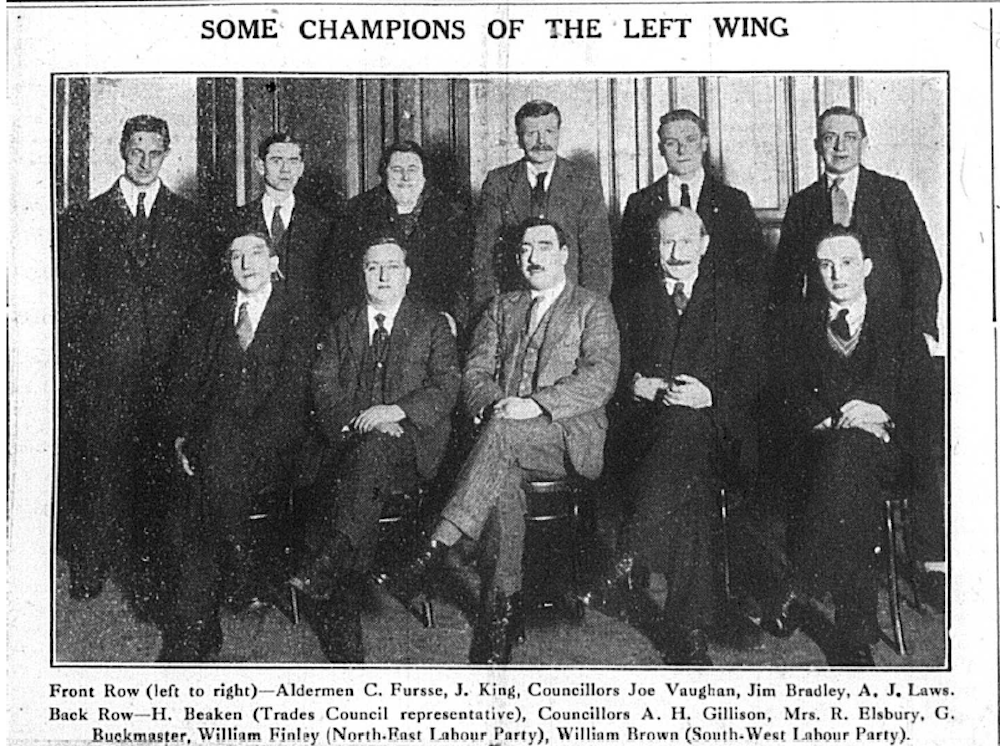

Andy Ford (Warrington South Labour Member) completes his article on the relationship between the Communist Party and the Labour Party in the 1920s. Part two deals with the period from 1926-1931. Part One can be read here. [Featured photo – Bethnal Green Trades Council and Labour Party, 1920s. Joe Vaughan 3rd from left front row]

*******

After the defeat of the General Strike, the political terrain became increasingly difficult for the Communists. Demoralisation in the movement freed the Labour bureaucracy from rank-and-file control and they set off on a relentless political witch-hunt, disaffiliating any party body that refused to exclude Communists.

The TUC entered into the Mond-Turner talks which urged a ‘common interest’ between the unions and business, and the Labour Party adopted a new right-wing programme called “Labour and the Nation”, while purges and expulsions increased.

The purge was not easy as the Communists were totally integrated into the labour movement in their localities. At that time there were no CLPS; instead the unions, socialist organisations and Labour Party membership were integrated into joint district, borough and divisional Labour and Trade Union bodies. In the Rhondda, the vote in favour of official affiliation of the local Communist Party was 12,090 in favour, with only 5,668 against; and no-one at all voted for exclusion of individual communists.

The September 1927, NLWM conference had 54 constituencies delegated and “many” groups, and in September 1928 they had 78 constituencies represented, and 80 groups.

However, the delegations increasingly came from borough and divisional Labour Parties that had been disaffiliated by the Labour Party bureaucracy for refusing to exclude Communists. Internal reports revealed the difficulties of running a shadow Labour Party, separated from trade union funding and official Labour Party status.

In January 1927 J.R. Campbell complained that outside London there was not even an NLWM bulletin, while in his defence the NLWM Secretary, Ralph Bond, said that he had to run the NLWM, on his own, “from one small office in London”. The NLWM national committee could only meet twice in 1928.

CPGB lacked a worked-out position

By taking in the disaffiliated parties the NLWM began moving from a group organising within the Labour Party to change it, to a group outside campaigning to replace it. This in part was due to the lack of a worked-out position on the Labour Party within the CPGB itself. On the one hand, the wing that had long been integrated into the Labour Party wanted to stay there, and as events moved on some members broke their links with the CPGB and took up the political position of the Labour lefts; on the other hand the wing that had grown up outside the Labour Party in the war began to say that the Labour Party had betrayed the working class, was finished, and needed to be replaced. Bond even described the official Labour Parties as “scab parties” and claimed that the NLWM were the “real Labour Party”.

The NLWM stood candidates in the 1928 London local elections, where 11 disaffiliated Labour Parties put up 22 candidates – getting a respectable 22,000 votes compared to official Labour’s 63,000. In South Wales NLWM candidates polled on average 64% of official Labour. These results only encouraged the idea of fighting the Labour Party at the ballot box.

But it was hard going outside the Labour Party. The London NLWM itself noted that that disaffiliation had had “disastrous consequences” for some of the rebel Labour Party bodies – “They were not strong enough to continue functioning and as a result went out of existence…..” Bond, the NLWM Secretary wrote that “…some of the defiant bodies had died… and had found themselves in a weak financial position…Working for disaffiliation at any price was not to be encouraged. The NLWM must learn to manoeuvre.” (Quotes from Lawrence Parker, ‘The National Left Wing Movement’).

But when the NLWM tried ‘discretion as the better part of valour’ in Manchester in late 1927 by accepting the expulsion of Communists and leaving the Labour Party under left control, voices were raised that it was a surrender to MacDonald’s bureaucracy.

“I will fight the Communist Party until I am dead” – Morrison

Just like today, it was a difficult tactical situation. The Labour right were on a mission for their masters – the British ruling class. Herbert Morrison (grandfather of Peter Mandelson) declared that “I will fight the Communist party until I am dead” and this was often reciprocated by the local Communists. It was difficult to enthuse CPGB members for such work. For example, in West Fife, a Labour Party ward said that “It would be a greater honour to be disaffiliated than affiliated with that gang in Eccleston Square” [Labour Party HQ]

– “I will fight the Communist party until I am dead”

In Gateshead a CPGB member stood up to speak and the Chairman forced him to sit down again, and when he refused, the meeting was closed. In Ogmore, South Wales – a vote on expelling Communists was refused because the NLWM would have won, and Cardiff Trades and Labour Council required all delegates to sign a paper to say they were not Communists before the meeting could start.

It was brutal and one-sided, even though the Communists were often the best campaigners and organisers in their area. In Cheltenham, the Labour Party members begged the Communist chairman of the borough party to leave the CPGB so that they could carry on working with him.

The decisive battle came in Bethnal Green, the stronghold of the NLWM and the CPGB. In 1924 Communist Joe Vaughan had been elected to the Exec of the London Labour Party with the second highest vote. He was barred as a candidate in March 1925 but the Bethnal Green Borough Labour Party ignored the instruction and in November, ran a joint ticket with 4 out of 5 communists returned. In Feb 1926 the Labour Party disaffiliated Bethnal Green, who remained defiant.

They pledged to maintain the £4 minimum wage – as had originally Woolwich, Bermondsey, Shoreditch, Stepney and Poplar. Vaughan wrote “One by one they have deserted us and now we find ourselves left alone in the struggle”. Then, within the Bethnal Green Labour group, the Communists increasingly clashed with a moderate group led by the new mayor, Charles Hovell.

Bethnal Green – victories and defeats

In a December 1927 byelection, the local Bethnal Green NLWM candidate beat official Labour by836 to 625. But there were problems in 1928; while Joe Vaughan beat official Labour by 1,976 to 789, the official candidates were victorious in the other seats. Some of the NLWM members re-joined the official Labour Party and in April 1928 the NLWM was defeated for all positions for the Guardians Board in the borough (All data from Parker ‘The NLWM’).

Then, in November 1928 both official Labour and the NLWM did badly in Bethnal Green, with the Liberals taking all 30 seats. The right-wing official Labour Party was not at all bothered at losing the council. Hovell said “We are not disappointed. We are shaking hands with ourselves because we have put the Communists bottom…in future the Communist Party will be wiped out…” It was the end of the road.

There was a final outing for the NLWM electoral challenge to Labour in 1929, in Birmingham, where despite a commanding presence in the local Labour Party and trade unions, this translated into a mere 1% vote in the election in Birmingham Moseley.

The 1929 CPGB conference decided to cut their losses, and a vote of delegates decided by 55 to 52 to wind up the NLWM and strike out on their own, as a fully independent Communist Party.

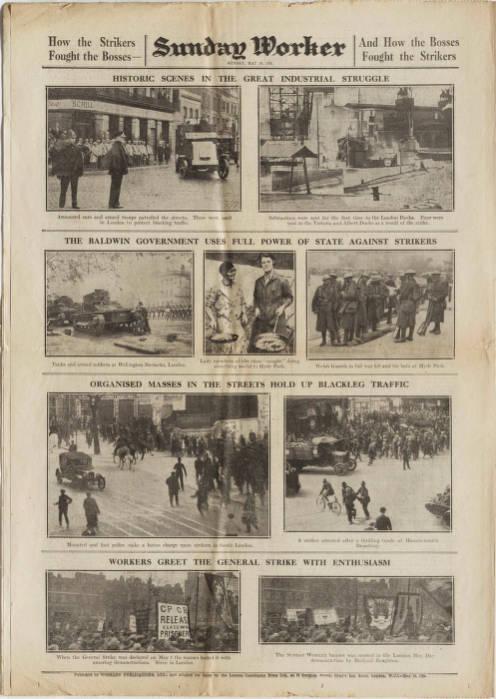

The Sunday Worker hosted a debate where Communists and left wing NLWM activists discussed the issues. A letter from Islington Labour Party pointed out that Lenin had advised the Communists to expose the Labour Party but not oppose it electorally so long as the mass of the working class supported it. The correspondent, Mr Rushton, (evidently a wise man) also advised against “wasting resources running candidates against the Labour Party” and wrote that the deficiencies of the Labour Party were clear to the activists, “…but not to the mass of workers”.

However Andrew Rothstein, a leading Communist writer, said there was no point asking anything from the Labour Party as it had “finally and irrevocably gone over to capitalism”. A delegate at the conference said that the NLWM was “Dying faster than we can keep it alive” and even Ralph Bond said that the NLWM was “ailing” and “obsolete”.

1929 – Communists abandon Labour

Contrary to received wisdom, the decision to abandon the Labour Party was not due to instructions from the Stalinist Communist International. In fact the Comintern wanted to continue with the NLWM tactic. It was the membership of the CPGB who voted to quit, reflecting their righteous anger at the Labour Party leadership, and frustration at the difficulties in the Labour Party. Following the CPGB conference the NLWM Committee voted to dissolve itself in March 1929.

While the frustration was understandable, the CPGB marched out of the Labour Party at exactly the wrong time, just as the mass of the working class were moving to elect the first majority Labour government in May 1929.

Just two years later, in 1931, a huge split and crisis developed in the Labour Party as Ramsey MacDonald, in the face of the capitalist crisis, went over to an open coalition with the Conservatives. In the context of a pure betrayal by the Labour leaders there was turmoil in the Labour Party with factions, debates and disputes over the way forward. Out of that came the radical manifesto of 1945.

If the CPGB, and the activists close to them in the NLWM, had just held their nerve the Marxist left would have been in position to play a decisive part in the Labour Party debates of the 1930s. Standing candidates against the Labour Party was a road to nowhere.

FURTHER READING

Lenin – Left Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder [https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/]

Mick Brooks – The First Labour Government

Trotsky – The Anglo Russian Committee’ [https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/britain/ch09.htm]

Lawrence Parker – The Communists and Labour: the National Left Wing Movement 1924-1929. Although Left Horizons would differ with Lawrence Parker on many of his political positions he has done an important service to the movement by going through all the original source documents that survive and giving a detailed account, possibly the only one written, of the day-to-day activity and organisation of the NLWM.