As the Labour right wing consolidated its grip on the Party and Keir Starmer binned the ten pledges that got him elected, there were many on that wing of the Party who imagined that the next general election would be 1997 all over again – a new era of Labour election victories and the firm establishment of their grip.

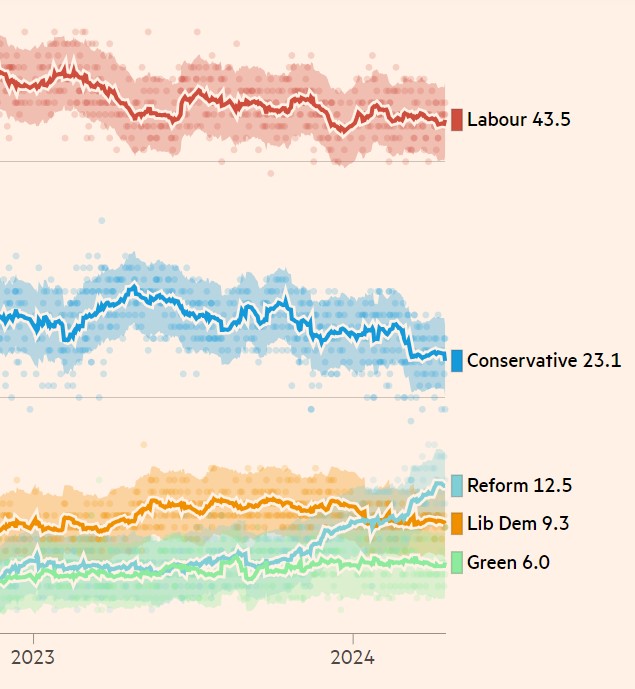

It certainly looks from opinion polls that Labour is going to win the next election: it is merely a debate over the size of the majority. Labour has a lead of around 20 per cent in the polls and no party has ever recovered from a 20-point deficit this close to a general election. If anything, the poll lead is still edging upwards.

In the demographics, it is only among the over-65s that the Tories have a lead – and that is by only 3%, down from over 40% just after the last election. But in every other age group there is majority of Labour support. Among under 24-year-olds, Labour’s lead is 45%; among 25- to 34-year-olds, it is 40%; among 35 to 44-year-olds, 28%; and among 45 to 64-year-olds, it is 13%. (Financial Times poll tracker analysis, April 3).

In a poll two months ago, Labour had a 30 point lead among those with mortgages, which is a turnaround from a deficit of 12% in August 2020. Among renters, Labour’s lead is a massive 45 points, in increase from 12 % over the same period.

A corrupt and incompetent government

Keir Starmer is riding a wave of anti-Tory sentiment unseen for decades. There is a gut feeling among millions that this government is incompetent and corrupt and that its only enduring policy is the impoverishment of the majority of the population for the benefit of the super-rich. From the crisis in the NHS, to sewage in rivers, to public services, to wages falling behind prices, to the cost of housing, millions are screaming out for change. Labour is seen as the only viable alternative, despite having a leader viewed with some suspicion and scepticism.

One would have thought with polls like these that Labour’s right wing would be euphoric, but they are not, and the reason is clear. It is beginning to dawn even on them, that 2024 will not be like 1997, that the economic scenario Labour will face on coming into office, will be a grim one.

“I recognise the dire inheritance we would have if we win the election,” Shadow Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, said in a speech in February. “I am not going to be able to turn everything round overnight. We are going to have to grow the economy. There will be a relentless focus on what we need to grow the economy.” (Guardian, February 28).

In January, a report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies warned of “painful choices that ‘cannot be wished away’, and added that the ‘miserable’ inheritance left after the election would require the next chancellor to make harsh decisions aimed at further bolstering tax revenue or bearing down on public spending”. (Financial Times, January 24). “For a chancellor with a goal of reducing debt as a fraction of national income”, the IFS report said, “things have arguably never been so bad.”

Real household income to stagnate at least two more years

Today, UK government finances are in a far more fragile state than they were in 1997. Total public sector net debt, expressed as a percentage of GDP, will be 98 per cent this fiscal year, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility. In contrast, it stood at just over 36 per cent in the 1996-97 fiscal year.

“Even though the UK is on track to exit the shallow technical recession of the third and fourth quarters of 2023”, the Financial Times explains (April 9), “growth is on a decidedly tepid trajectory. Gross domestic product will rise by just 0.8 per cent this year — and per head it will fall by 0.1 per cent, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, the fiscal watchdog. Real household disposable income will not regain its pre-pandemic peak until 2025-26”.

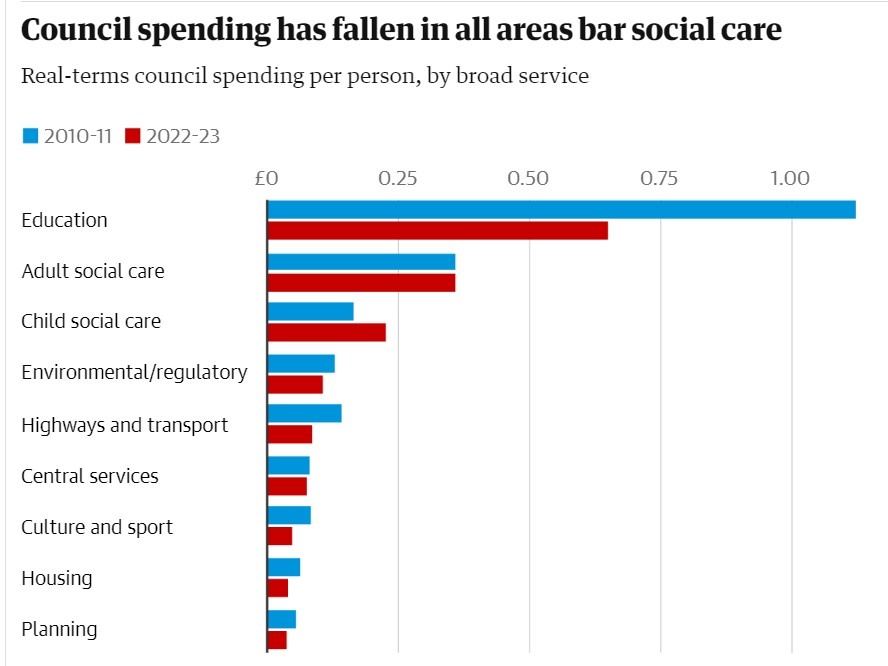

It is because the Labour leadership will find themselves in such a dire situation, that they are promising virtually nothing in terms of additional public spending – for public services, for example – nor additional taxes, like a wealth or windfall tax. Worse, they will be hemmed in by public expenditure cuts and tax rises already ‘baked into’ future government budgets by successive Tory chancellors an estimated £45bn of unfunded tax cuts.

The only good news, according to Martin Wolf, the Financial Times chief economic commentator, is that “it will be hard for economic performance to get worse”. The bad news for Labour, he adds “is that it will also be hard to make it much better”. (Financial Times, April 1). Wolf, as ever, is a master of understatement.

Wolf repeats the word most commonly used in describing the state of the British economy: “grim”. “In 1997”, he writes, “the incoming New Labour government, led by Tony Blair, enjoyed the luxury of rapid economic growth: according to IMF data, it averaged 3.4 per cent a year from 1997 to 2001, inclusive. Gordon Brown, his chancellor, had a cornucopia to distribute. Reeves, if she indeed becomes chancellor, will not”.

The worst combination of problems since the Second World War

“This is the worst combination of problems at home and abroad that any government will have taken on since the second world war,” former Tory Chancellor Ken Clarke told the Financial Times. It is abundantly clear that in economic terms, Labour will come into office hitting the ground stumbling.

What is important for us to consider is how this crisis will translate into policies that affect workers and, even more importantly, how workers – and their trade unions – will react. Despite appeals from the Labour leadership for “patience” and “restraint”, the trade union membership, often despite the union leadership, will be expecting real change and real improvement in their lives.

It is not only the repealing of Tory anti-trade union legislation and the promised ‘new deal for workers’ that the unions will expect. It will be meaningful improvements and investment and a recoverty of public services, especially the NHS, and workers will not be fobbed off so lightly.

The Tory-lite policies that Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves are promising arise from the fact that, like so many Labour MPs, they base their entire outlook on the preservation and continuation of the capitalist system, an economic system built on rent, interest and profit for a tiny handful of the population. It is not a matter of the personal wishes of ministers (although, with Labour’s right wing we would question that), but the logic of the economic system that will drive the Labour government towards ‘Labour austerity’.

An unprecedented postwar crisis in living standards

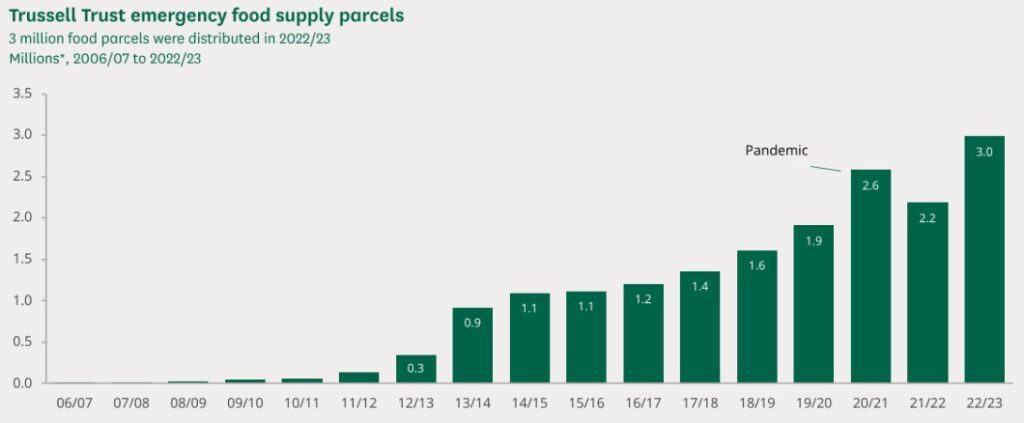

There is a crisis in living standards facing the big majority of the population and it has not arisen by accident, but by the necessary exigencies of the so-called free-market system. Homelessness, NHS waiting lists, food banks, sewage dumping – to name a few – are all at record levels, despite the UK still being the fifth or sixth most wealthy country on the planet.

No wonder there is a widespread public perception that the ‘system’ is working only for the benefit of the very rich: 39% of people, research shows, rank the very rich as most powerful force in the country, compared to only 24% who think government hold the real power. It is not an incorrect perception.

If Labour were a socialist party, facing such desperate times, it would call for urgent measures. It would appeal to workers in unions, in workplaces and in communities for their support in taking over the banks, financial institutions and big companies to run the economy democratically in the interests of all, through a plan of investment and resources aimed at raising living standards.

It would aim the entire thrust of its policies against the vested interests of the rich and super-rich, the tax-dodgers and those who fleece the public day in and day out. It would challenge the fundamental basis of the economic system.

Just to take one example – the privatised water companies. They have taken out tens of billions in dividends, while loading the companies with debt, after having been privatised with no debts at all. If a Labour government renationalised these utiliites without any further compensation, it would get massive public support. Let those who have ripped off the public pay the cost.

But unfortunately, the leadership of the Labour Party is far from being socialist even in words, much less in deeds. They will find, however, when they are elected into office in the next year, they will get a rude awakening. There will be little in the way of a honeymoon period. A new bout of ‘Labour’ austerity, new rounds of public spending cuts and a squeeze in living standards will produce a storm of protest, inside and outside the Labour Party, especially in the trade unions. We will see then how much of a grip the right wing really has on the Party.

[Top picture, Labour front bench in House of Commons from BBC live feed]