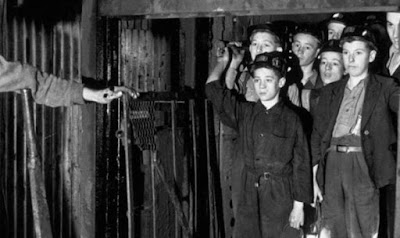

By Cain O’Mahony [photo shows “Bevin Boys” – conscripted miners in Cramlington, Northumberland]

Eighty years ago, there was a political storm across Britain as trade unionists fought for the right to strike – and a small band of Marxists found themselves at the epicentre of the struggle.

In Britain during World War II, the leaderships of the Labour Party, TUC and – after 1941 – the Communist Party, all declared a ‘class truce’, to stop industrial action that could hamper the war effort. Labour Ministers held positions in Churchill’s coalition government.

The traditional militants on the shop floor, the Communist Party, had transformed themselves after the invasion of the Soviet Union. Now, the Communist Party had become a mere adjunct of Stalin’s foreign policy. This demanded no disruption of industrial production in the capitalist West, and indeed support for ‘speed ups’, to ensure the western allies could launch a ‘Second Front Now’. This class collaboration, combined with a political programme that adhered to Stalin’s Popular Front policy, meant the CP abandoned any last vestiges of revolutionary class politics.

By 1944 however, realisation dawned amongst many workers that the war was beginning to be won. This brought new confidence to the working class. For the previous five years, with the threat of invasion, the Blitz and the seemingly unstoppable advance of Nazi Germany, they had been prepared to accept all the sacrifices demanded of them in the name of the ‘war effort’ .

But now, workers were less inclined to counterpose their ‘duty’ to defend their country against the deprivations that had been imposed upon them. Frustration at their working conditions and pay burst forth, and the number of industrial disputes soared.

100,000 miners walk out

In the Spring of 1944, strikes escalated throughout the country. In the coalfields, 100,000 miners walked out. They were not just demanding better pay and conditions but also the nationalisation of the mines, angry that the pit owners were still making huge profits from the war effort. Meanwhile, 50,000 workers went on strike in the munitions plants. In the engineering sector, unrest was compounded by a series of layoffs, as arms production in the USA reached unprecedented heights, displacing British arms production.

Nowhere was the unrest felt more sharply than amongst the young apprentices. For the government, there appeared an obvious solution to the engineering downturn. Engineering apprentices could be switched to work in the mines; Minister of Labour, Ernest Bevin introduced the ‘ballot scheme’. There was fury amongst the apprentices, who now faced cuts in pay, the chance of a better paid engineering career taken away from them, not to mention a hard and dangerous life below ground as a ‘Bevin Boy’.

The flashpoint came in Newcastle. A Young Communist League activist, Bill Davy, became a key organiser in the Tyneside Apprentices Guild, and prepared them for strike action. This infuriated the Stalinists in the Communist Party, but their several attempts to oust him from the leadership of the apprentices failed.

Cut off from the Communist Party, Davy understood the proposed strike action could not succeed in isolation from the rest of the labour movement. He would need to look elsewhere for solidarity.

With the Labour Party shutting up shop for the duration of the war and the Communist Party effectively policing the labour movement to stop industrial action, the main active groups remaining on the left were the remnants of the Independent Labour Party, and the Trotskyists in the Revolutionary Communist Party.

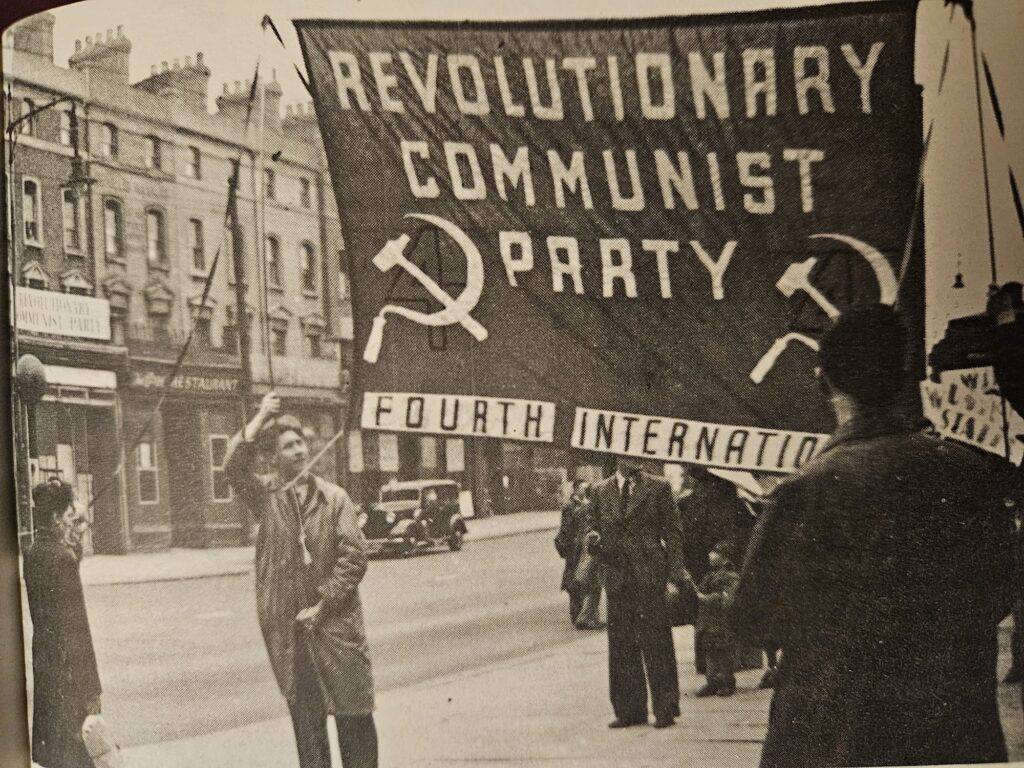

The RCP (not to be confused with various latter-day organisations that claim the name) was the official British section of the Fourth International, founded by Trotsky. The leading lights of the RCP were Ted Grant, Jock Haston and their industrial organiser, Roy Tearse.

Revolutionary organisation

There is not space here to outline the machinations and intrigues that went on in the Fourth International following Trotsky’s assassination in 1940. But briefly, during the war years, the Grant group, previously expelled from the International, had successfully built a revolutionary organisation, the Workers International League (WIL). This impressed the new leadership of the Fourth International, who urged the WIL to merge with other much smaller so-called Trotskyist organisations to form the RCP.

With the Marxists around Ted Grant and Jock Haston easily in the majority in the new organisation, they agreed. The ‘Revolutionary’ part in the new formation’s title was to differentiate it, in the eyes of workers, from the collaborationism of the Communist Party.

Although numbering only several hundred, the RCP were a cadre organisation, with most members holding positions in the labour movement at local and workplace level, and they were mainly recruiting members of the CP disgruntled at their party’s abandonment of the class struggle. More importantly, the RCP still orientated to the mass labour movement, despite the difficult political conditions.

Previously, the WIL’s first major intervention had come in 1942. A series of strikes had broken out on the Clyde, after 90 workers faced fines or imprisonment for striking against working conditions. A Clyde Workers Committee was formed, which in turn appealed to trade union activists in mainly the ILP, the WIL and anarchist organisations, to join them in a conference to discuss forming a national group that could support any group of workers in the country who found themselves in the same position as the Clyde workers – not just politically, given the abdication of the Communist Party and the official Labour and TUC structure, but also financially through shop floor collections. The result of the conference was the establishment of the Militant Workers Federation, with Tearse elected as its national secretary.

For Bill Davy, the only group on Tyneside still providing vocal opposition to the ‘collaborationist’ stand of the labour leaders and the Communist Party, was the local ILP branch. However, the new RCP – through lack of any alternative while the Labour Party had ‘shut up shop’ – was continuing political work inside the ILP on Tyneside.

Striking apprentices

Davy turned up at an ILP committee meeting demanding a discussion on the forthcoming apprentices strike. He was welcomed by the local RCP members there – Heaton Lee, Jack Rawlings, Ken Sketheway and Ann Keen. After pledging their support, Tearse was sent for, and he began to organise solidarity action through the Militant Workers Federation. The Tyneside strikers were soon joined by more striking apprentices in Clydeside and Huddersfield.

Unbeknown to them, the RCP’s intervention in the apprentices dispute set off a chain of events that would propel them into the national arena – and into prison.

The British Security Services had been taking a closer interest in the RCP, since the successes of the Militant Workers Federation on the industrial front. In the summer of 1943, MI5’s F2a Section had sent out instructions to Special Branch units in regional police forces to start investigating and putting the Trotskyists under surveillance. A later MI5 report in 1945 outlined the infiltration they had carried out:

“Following advice from F2a, police forces placed agents in the RCP…many of the more enterprising forces undertook their own regular investigations, and by the end of the war at least five police agents had been placed in the movement. Two of these (Glasgow and Birmingham) produced first class information of general interest”

[Document KV4/56, M Section, 1945, Public Records Office – reproduced in Revolutionary History by Ted Crawford, November 1999].

The information provided by the security services was a godsend for the government. The mass strikes of early 1944 – which, with the exception of the apprentices, the RCP had little influence in, and certainly no responsibility for – had caused consternation amongst the US Government, as it amassed its forces in Britain for the assault on France. They put enormous pressure on Churchill to quell these strikes, and quell them quickly, and get power and munitions production back on schedule for D Day.

The Churchill Government could not attack the strikers directly for fear of antagonising the already volatile shop floor even further. Neither could they attack their traditional whipping boys, the Communist Party, who were doing more than anyone else to contain the strike wave; it would also have put pressures on the alliance with the Soviet Union.

Terrorise the labour movement into submission

Therefore it was the RCP’s head which fitted perfectly onto the sacrificial plate, to be offered up to the Americans, as evidence that the British government was ‘cracking down on militants’. A move against the RCP was anticipated to terrorise the wider labour movement into submission, without the threat – given the RCP’s limited base within the movement – of provoking further strikes.

To prepare the public for the witch-hunt, the security services leaked reports to their contacts in the media. On 3 April 1944 the Daily Mail led the media charge, writing darkly of “drastic action” about to be taken against the RCP.

Following the media ‘horror stories’, the right-wing TUC leaders joined the hysteria and on April 5, 1944, condemned the apprentices’ strike action as “a blow struck in the back of their comrades” in the armed forces.

This gave the green light for the state to act. On the same day and continuing into the next, there were police raids on the RCP headquarters in London, and RCP’s members’ homes in Nottingham, Glasgow, and of course, Wallsend and Newcastle.

The Labour Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, prepared a report for the war cabinet to justify the action, based on the Special Branch ‘reports’ from police informants. Home Office warrants were granted for the tapping of phones and the opening of mail. Then came the arrests.

Heaton Lee and Ann Keen were picked up in Newcastle on 8 April and transferred to Durham gaol. Tearse was arrested in Glasgow on 11 April, and transferred to Newcastle. Davy was held by the police all day until he ‘volunteered’ a statement.

On the run

The police had less luck with Jock Haston, who was travelling the country on a speaking tour. Realising he could not stay on the run forever – and that there was much political capital to be made out of the clampdown – he eventually gave himself up on 26 April.

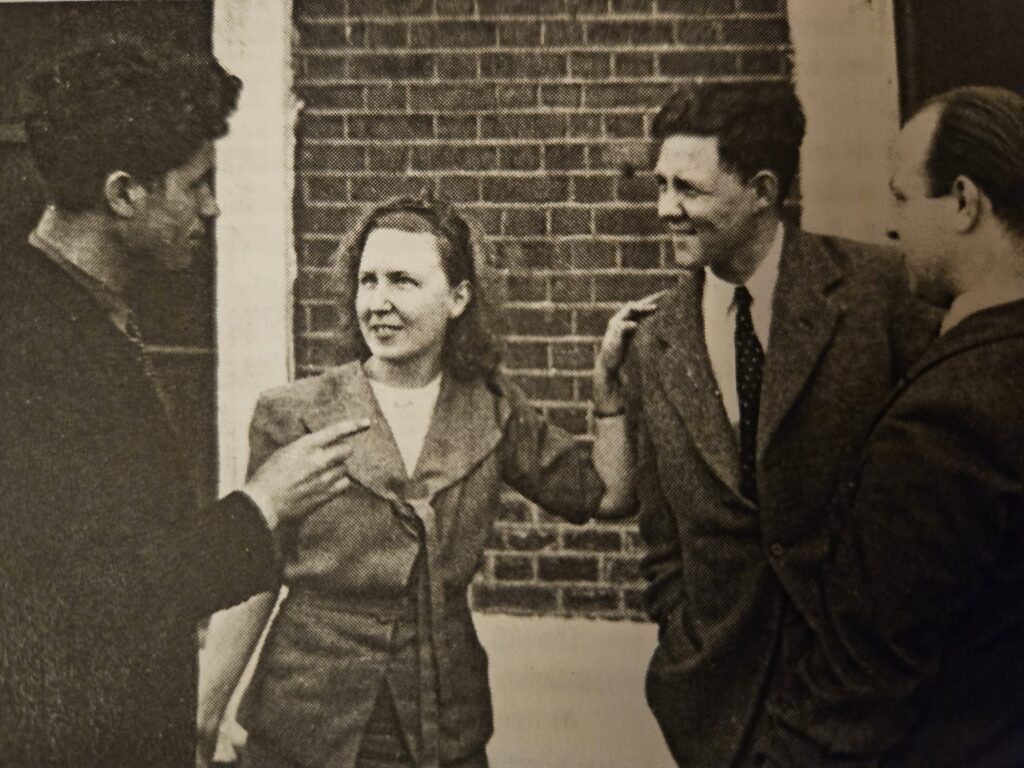

Jock Haston, Ann Keen, Heaton Lee and Roy Tearse

To add to the clamour, the media – particularly the early tabloid variety – had been quite excited about the arrest of Ann Keen. Not only was she a blonde, but she had hurriedly pulled on a pair of trousers on her arrest. This was the stuff for the salacious end of Fleet Street: blonde revolutionaries wearing trousers! Shock horror!

But problems were only just beginning for the Government. They made the fatal error of charging the RCP members under the Trades Disputes Act 1927 – the hated legislation introduced after the 1926 general strike, with its draconian penalties of fines and imprisonment for strikers in essential services and those who called for strikes.

It had not been used before, for fear of provoking widespread industrial unrest. The government understood this, so just to make sure, Ernest Bevin decided to bring in yet further repressive legislation, which in their eyes would be one that could be separated from the ‘bad old days’ of the general strike, and instead be associated with the need to execute the war efficiently and thus be easier to ‘sell’ to the labour movement.

After agreement from the TUC leaders, Bevin introduced Defence Regulation 1A(a) which could not only inflict fines and imprisonment on strikers, but also upon those who ‘instigated’ strike action. Now anyone who even just called for strike action could be imprisoned. The two issues of the arrests of the RCP members and attempts to introduce new anti-trade union regulations became intertwined.

There was uproar amongst the labour and trade union movement, including amongst the left wing of the Labour Party. In Parliament, Aneurin Bevan bitterly opposed the arrests and put an order paper down to annul Defence Regulation 1A(a). Later in May in the subsequent debate, 23 Labour MPs voted against the regulation, with, significantly, a further 145 abstaining, about a third of the Parliamentary Labour Party.

In the debate, the ILP MP John McGovan summed up the absurdity of trying to blame a small band of Marxists for the wave of industrial unrest:

“I saw the agitation that was carried in the Daily Mail, practically alleging that these strikes were the result of some deep-rooted Trotskyist plot, and that some young lady – a blonde in corduroy trousers – had been assisting in bringing the workers out on strike…Does anyone suggest that 100,000 miners were on strike because of some Trotskyist plots?”

[Hansard, Vol CCCIXXXXix, reprinted in Socialist Appeal, 22 May 1944].

Communist Party abuse

There was of course no such solidarity from the Communist Party. Their paper, the Daily Worker plunged to new depths of personal abuse after the arrests and the raids on the RCP:

On Ted Grant (originally from South Africa): “…all he knows about the British working class movement might have been picked up on the back veldt….”

On Jock Haston: “…all this man ever did in the working class movement in his native city could be put on the back of a penny stamp…”

On Roy Tearse: “…a third rate, inefficient shop steward….”

[Bornstein & Richardson, Two Steps Back, 1982]

All the Communists could bring themselves to do was to condemn Bevin for the introduction of Regulation 1A(a), but only on the basis that there was enough standing legislation currently available with which to deal with the Trotskyists.

The Communist Party aside, however, there was widespread opposition from the labour movement. The national conference of the ILP unanimously opposed the arrests, and played a pivotal role in establishing the ‘Anti-Labour Laws Defence (ALLD) Committee’.

Chaired by the ILP veteran Jimmy Maxton, the ALLD Committee included MPs from both the ILP and Common Wealth parties, but also nine Labour MPs, including Aneurin Bevan and Sydney Silverman – the latter was significant as it was his brother Ernest, an extremely skilled lawyer, who would play a key role in the fight. Representing the RCP, Ted Grant was also on the Committee, on behalf of the imprisoned members.

The Committee’s campaign attracted wide support, including from the largest miners’ lodge in South Wales, the Belfast shop stewards committee, and trades councils from most of Britain’s industrial areas. One of its largest meetings was held on Clydeside, attracting an audience of over 3,000 trade unionists and raising £500 (nearly £28,000 in today’s money) for the campaign fund.

Opposition within armed forces

One further alarming development for the Government was the opposition from within the armed forces. Serving RCP members had been making much headway building support in the 8th Army, which had received hero status amongst the British public after its victory at El Alamein in 1942.

Given the base the RCP had built, the plight of the imprisoned RCP members soon circulated amongst armed services personnel. A petition was passed around the 8th Army’s Signal Corps who made it known they supported the right of workers to strike. Such was the pressure of the campaign that even the official army newspaper, the Eighth Army News, carried a sympathetic article in May 1944 headlined; “RIGHT TO STRIKE IS PART OF THE FREEDOMS WE FIGHT FOR”.

At the trial of the ‘RCP four’, the jury dismissed 11 of the charges, but still upheld two of them. Heaton Lee and Tearse were sentenced to 12 months in prison, and Haston to six. Having already spent 13 days in gaol (and no doubt with an eye to the media interest), the court released Ann Keen.

Despite the sentencing, the furore in the labour movement showed no signs of abating – Aneurin Bevan narrowly escaped expulsion from the Labour Party for continuing to lead the charge against Bevin in Parliament. The government knew it had to back down, fearful of a new labour movement backlash, but also nervous about the opposition growing in their own 8th Army.

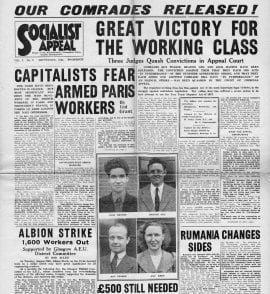

The case went to appeal in October 1944. Under the legal stewardship of Ernest Silverman, all charges were dropped and Haston, Heaton Lee and Tearse were released to a heroes’ welcome at a victory rally held at St Andrews Hall in Glasgow. The RCP’s paper declared:

“It is of no small importance to the organised working class that upon the first occasion the ruling class tried to use this infamous Act, they have suffered a defeat…It will be harder to use it against labour militants in the future now that a victory for the working class has been effected in the first legal struggle”

[Socialist Appeal, 6 October 1944]

In fact Defence Regulation 1A(a) nor the Trade Disputes Act 1927 were ever used again. One of the first measures of the 1945 Labour Government was to repeal them.

Today, we must show the same tenacity to ensure the next Labour Government quashes the Tories’ current attempts to bring in strike bans and penalties on trade unionists, and once again defend the ‘freedoms we fought for’ in 1944.