By Greg Oxley

Today is the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the revolution in Portugal, a process that unfolded over many months. Greg Oxley, editor of the French Marxist newspaper and website La Riposte, describes the background and the events. This is the first part of a two-part article.

The Portuguese Revolution of 1974-1975 abruptly put an end to half a century of military dictatorship. It began, as have many revolutions in history, when longstanding divisions in the ruling class, the state bureaucracy, and the army, broke out in open conflict. The gaping breach, in what had previously appeared to be an unsurmountable wall of reaction, opened the way for a tremendous mass movement from below.

Moving into action to win and consolidate basic democratic freedoms, the Portuguese working class, together with the poorest and most downtrodden layers of rural society, rapidly steered the course of events in a socialist and revolutionary direction, striking at capitalist ownership of industry, banking, and land, and therefore at the very root of all forms of oppression and exploitation in the modern world.

Regime based on the suppression of all democratic rights

Until 1974, Portugal had known nothing but dictatorship since 1926, when a military coup d’état swept away the chaotic First Republic, which was set up after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1910. Antonio de Oliveira Salazar had been Finance Minister under the military regime, before becoming Prime Minister in 1932. A vicious opponent of socialism, trade unionism, and of even the most basic democratic rights for working people, Salazar ruled in the interests of the rich and powerful, of the capitalist corporations and big landowners.

His regime was based on the maintenance of ‘order’ by the army, the police, and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. Press, radio, schools and higher education, all forms of public expression, were tightly controlled. Relegated to the status of an economic and cultural backwater of Europe, Portuguese society was frozen in a sort of political, social, ideological, and moral straitjacket.

Opponents of the regime were imprisoned and tortured. Many of them disappeared forever at the hands of the dreaded secret police, the PIDE, to be renamed the DGS or “Directorate-General of Security” in 1968, but still commonly referred to as the PIDE in the 1974 revolution.

The activities of PIDE were not limited to Portugal. Modelled on the lines of Hitler’s Gestapo, it played a role on the side of General Franco during the Spanish Civil War, and also in the murderous colonial wars waged by Portugal in Africa. In 1936, when an attempt by mutinous Portuguese sailors to deliver two warships to the forces fighting against Franco was thwarted, they were imprisoned and tortured by Salazar’s police in Tarrafal (Cape Verde), where many political prisoners were to suffer and die over the following decades.

Salazar had a stroke in 1968, two years before his death, and was replaced by Marcelo Caetano, formerly Minister of Colonial Affairs. At the time, Portuguese imperialism was desperately trying to hold onto its colonial possessions in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bassau. As with French imperialism in Algeria, Portugal’s armed forces committed widescale atrocities against the indigenous peoples.

Massacre in Mozambique by Portuguese troops

Just weeks before Caetano was due to visit Britain, in 1973, to celebrate the anniversary of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance, a British Catholic priest exposed in horrific detail the massacre of all the men, women, children, and even newborn babies, in the village of Wiriyamu in Mozambique. This had been part of a campaign of shootings, hangings, beheadings, rape, torture and forced depopulation along the Zambezi River, initiated by the Portuguese army and the PIDE in 1971.

France had been defeated by the Algerian revolution, and in the eyes of many military commanders, politicians, and, most importantly, many junior officers and ordinary soldiers, Portugal was clearly heading towards a similar fate. The wars were swallowed up to 40% of the meagre resources of the state, in a country with a stagnant economy. The majority of Portuguese people were desperately poor, and were now badly hit again by the world economic crisis of 1973.

While a handful of extremely wealthy families gleaned benefits from the ongoing slaughter in Africa, the financial and human cost of the wars weighed heavily upon the middle class, and especially upon the workers of town and country. Sporadic illegal strikes and student protests were taking place and Caetano implemented a few superficial reforms in an attempt to appease the people. Press censorship was slightly eased.

But the problems ran too deep, and the attempts at reform were taken as a sign of weakness. The simmering class antagonisms in civil society were also reflected within the armed forces themselves and this would prove to be the Achilles’ heel of the dictatorship.

The scale of the wars in Angola and Mozambique entailed an expansion of the armed forces and increased military expenditure. On the advice of the white supremacist regime in Rhodesia, [Now Zimbabwe] Caetano introduced a law in the summer of 1973, opening positions of commissioned officers to young soldiers and militiamen after only minimal training.

Some officers had radical and socialist ideas

This reform caused enormous resentment among many junior officers who saw this “fast track” system of promotion as a threat to their careers and to the prestige attached to their own positions. The controversy led to the emergence of an opposition movement within the army referred to as the “the captains”, and later as the MFA, or “Armed Forces Movement”.

The MFA provided an organised focal point to the growing discontent within the army. It stood for an end to the colonial wars in Africa, a change of regime in Portugal, and democracy. Some of the junior officers had radical and socialist ideas, and some had links with the banned and therefore clandestine structures of the Portuguese Communist Party.

However, despite these leftward leanings, the amorphous and confused political character of the MFA was shown by its association with General Antonio de Spinola, who had been fired from the army in early 1974, following the publication of a book, Portugal in the Future, which argued for withdrawal from the wars and for the maintenance of the colonies in the form of a “federation” with Portugal.

In his youth, this extremely reactionary general had been a military observer at the siege of Leningrad, in the 1940s, on the side of the Nazis. Before that, he had fought on the side of Franco in the Spanish Civil War. He was no radical and in 1974, his political standpoint was clearly on the extreme right of Portuguese politics.

Another figurehead of the MFA was Colonel Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, who had served in Guinea-Bassau and in Angola. He was photographed weeping profusely over Salazar’s coffin, in 1970, but in the early 1970s he moved to the left and became a spokesperson of the MFA. As a colonel, he gathered the captains around him and won them to the idea of organising a military coup d’état to get rid of the Caetano regime and withdraw from the colonial wars.

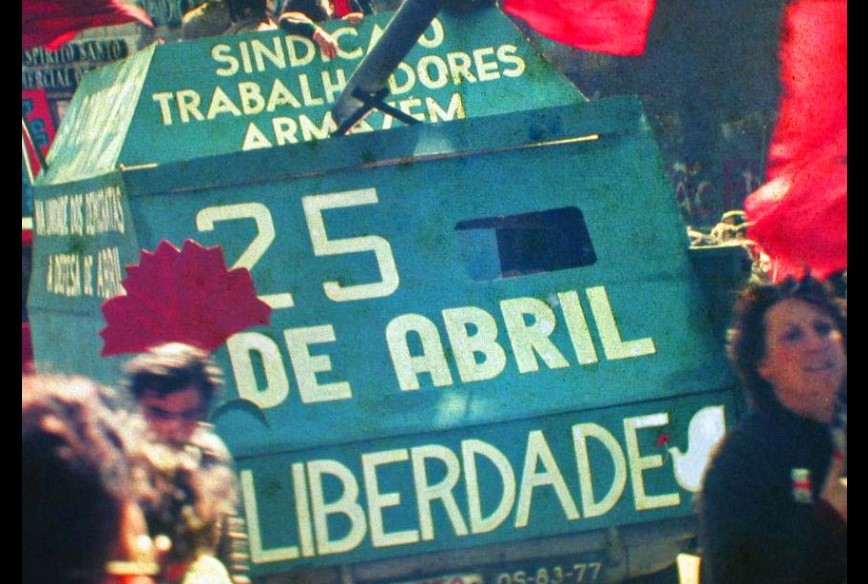

The coup was meticulously planned and carried out in the night of April 24/251974. Incidentally, one of the two songs put out on the radio which were to be the signal for the start of the operation was Portugal’s entry in the Eurovision Song Contest of that year. Who would have thought that Eurovision would spark a revolution?

The coup was supported by most of the ranks and junior officers of the armed forces. Four people were killed in the revolt, all of them shot by the PIDE. Caetano and his ministers, holed up in barracks in Lisbon, were rapidly surrounded by rebel troops.

However, he refused to resign to lower officers, which, he said, would be “like throwing my power into the gutter”. The rebel forces could easily have forced the issue, but chose instead to call on general Spinola. Caetano surrendered to him and was led away, together with his ministers. And so it was that the counter-revolutionary general Spinola, who had played no part in the preparation of the coup, and whose personal and political connections were with its enemies, was able to style himself as the figurehead of the revolution!

Provisional Government established under Spinola

A Junta of National Salvation, composed essentially of generals, assumed governmental power until May 16, when a Provisional Government was installed, including moderate “independent” political figures, and representatives of the Popular Democratic Party, the Democratic Movement, the Socialist Party and the Communist Party. Spinola, as president of the new republic, hoped to be able to ride out the storm, curtail the revolution and protect capitalist interests.

However, the overthrow of Caetano had the effect of spurring a movement from below which would push events in the opposite direction. Workers moved to take over factories and workshops. On the great landed estates in the south of Portugal, the peasants and wage workers occupied the land and threw out the landowners. Junior staff took over hospitals, expelling the senior consultants and the old administrators.

A similar process was underway throughout the economy and the state infrastructure. The working people were moved into action en masse to take control of society and reshape it in their own interests, striking down bosses and authorities that were associated with the oppression of the past.

From a takeover at the top with limited aims, the weeks following April 25 saw the development of a mass revolution from below. Hundreds of thousands of people poured into the streets of Lisbon to celebrate the overthrow of Caetano. Less than a week later, on Mayday, May 1, an estimated 1.5 mn people marched through the city.

Socialist ideas had a mass following

Once the mass of the people had moved onto the stage of events, soldiers and workers shared their ideas and experiences; they fraternised and saw themselves as participants in a common struggle. The need for “socialism” – whatever the precise content of this term might have been in the minds of those involved in the movement – was a widely accepted idea, expressing the desire for fundamental social change, for the emancipation of the exploited and oppressed.

The political parties of the left, banned in Portugal and their leaders in exile or in prison under the old regime, rapidly filled out with a mass membership and found themselves with a powerful basis of support within society. The same was true of workers’ organisations in factories and workplaces, and of rural workers’ associations of various kinds.

By the autumn of 1974, more than half of Portuguese workers were unionised. What was lacking, however, was some form of overarching, unifying, organisational structure akin to that which had emerged in the revolutions of 1905 and 1917 in Russia. One of the reasons for this was undoubtedly the role of the leaderships of the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, who strove to avoid the independent, united, self-organisation of the working people on a national scale.

As for the MFA, it’s various political strands all professed allegiance to “democracy” but it had no social and economic program worthy of the name. The conscious, organised, intervention of the working class had not figured in their plans, and they now found themselves riding, as it were, on the back of a tiger that seemed to be taking them in a direction they had not bargained for.

The reactionary elements at the top of the armed forces had lost control of the ranks. Apart from the fascist torturers of the PIDE and some relatively isolated elements within the army, the capitalists and reactionaries who had held sway in Portugal throughout five decades of dictatorship very quickly found themselves without any reliable forces to defend them.

The road to the socialist transformation of society seemed open, and real power – meaning effective control and management over the economy and the establishment of a new state apparatus representing the power and interests of the working classes – was within reach. However, this magnificent movement in the direction of socialism was thwarted by the MFA and the Socialist and Communist leaders.

As the course of events over the coming months would show, their indecision and naivety, at best, or, at worst, conscious betrayal, would prove to be an obstacle to the successful conclusion of the revolution. In time, this would allow the forces of reaction to recover and strike back.

The decline and eventual defeat of the Revolution dealt with in Part Two of the article, can be found here.