Throughout this 40th anniversary year of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular bulletins on important issues and developments that occurred during the strike, month by month, as well as specific articles analysing major events. This bulletin covers the period from late March to 20th April 1984.

*******

As March turned into April, the progress of the strike followed a number of key themes; the continuing efforts to spread the strike – pit by pit, area by area; the increasing clamour from the Tories and the right-wing union leaders for a national ballot; the growth of violence from the police at pickets; the call for solidarity from other workers and unions and some good national and local responses; and growing community and women’s support.

Spreading the strike

In spite of the decision by some areas of the NUM not to join the strike, more examples of successful picketing were being seen. There was still a strong hope and belief that most miners, even in non-striking areas, would eventually come out in support. Pickets from striking areas travelled to non-striking areas. Miners from South Wales and Kent travelled to Leicester, where they reported support especially from younger miners, as they could see that they would have no future if the pits closed.

One report in the Militant told the mysterious story of miners who had got into Nottingham via “clandestine methods” from Derbyshire, where the police thought they were literally “flying pickets” that had fallen from the sky! Miners from Kellingley in South Yorkshire apparently were on a “nature ramble” near the Nottinghamshire border. As the police addressed them one miner said “Look, boys, a pussy willow!” Sadly, the police arrested them anyway, for who knows what – walking in a field near Nottinghamshire perhaps [Militant 6th April].

Lancashire NUM leaders did not call on members to join the strike but delayed until a ballot could be held. Although the vote to strike was higher than ever before, in this traditionally moderate area, the vote ballot was lost. Nevertheless, miners in Sutton Manor colliery and Bold colliery voted to strike and to picket other pits to persuade miners not to cross.

From Durham, it was reported that open strike committee meetings were held every week to involve people in planning picketing, fundraising and the general organisation of the strike. Some had said that miners with cars or mortgages – so-called “middle-class miners” – would not strike but they did, especially the younger ones.

At Cynheidre pit in west Wales the recently-deposed lodge chairman called a meeting, hoping to reverse a decision to strike. The resulting vote was 80 percent in favour of staying out! As one miner said “We’ve been out for four weeks. What’s the point of going back now – Let’s go all out to win.” [Militant 20 April]

In Scotland, a letter to Militant [April 20] from Chris Herriot and Alex Shanks pointed out that although Monktonhall pit, near Edinburgh had originally voted not to strike, they had eventually come out.

One issue that needed to be carefully explained was the cynical trick of redundancy payments, that could tempt older miners. Kenny Summersgill, another miner from Monktonhall explained the reality:

“The older men are told they are going to get £1,000 for every year they have worked. That’s the impression that’s been given by the media, but they don’t show you the small print, which says that it’s subject to you having been earning £165 per week on average. And they are going to be asked to live off this money by the DHSS [the former name of the DWP – ed]; they are going to lose their coal allowance and other benefits.

To live a decent life you are going to need £5,000 a year in your hand; maybe if you’re lucky you’ll get a week at the seaside, things are going up so fast. For every five years they’ve worked they are going to have enough to keep themselves on for a year – £30,000 is pennies nowadays when it comes down to it, six years’ wages, that’s all. A lot of people will be wanting to buy a car and do this, that and the other, but what they don’t realise is that when the money has gone, they are accountable to the DHSS about why they squandered it. They can turn round and say, “Oh, you’ve got a car – well you can sell that so you can live off the money.”

After that you’re on the buroo [benefits – ed] like everybody else, and your TV’s not going to stay new, your carpet’s not going to stay good, your clothes are going to wear out, and you are going to start missing going down the club and that week’s holiday with the kids.”

[Militant 20 April 1984]

Nottinghamshire strikers

In Nottinghamshire, it should never be forgotten that thousands of miners were actually out on strike. At Blidworth, for example, 200 miners out of 460 were out while at Clipstone, 75 percent of the afternoon shift came out and 90 percent of the night shift.

On 20 April, Militant quoted John Robinson from Cotgrave colliery, who put the case well:

“Every miner should remember that the present good wages and conditions enjoyed by Nottinghamshire NUM members have only been won by building a strong and united union nationally and by sacrifices and solidarity of past generations of miners.

“I would like to make an appeal to other miners, firstly to those outside Nottingham to remember that we are not all scabs, but more importantly to appeal to miners in Cotgrave and Nottingham for unity in action. This fight is about saving jobs. We will win, but quicker and better if we stand together”

[Militant 20 April 1984]

The divisions ran deep as in some pits, half the workers were striking while the others were working. This was a fatal weakness. Many years before, from 1926-37, there had been a breakaway “Industrial union” in Nottinghamshire led by Spencer and Varley. The bosses made joining the scab union a condition of work and many miners were blacklisted for several years. The same divisions would resurface later in 1985 as the Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM) was formed in opposition to the NUM. Such divisions only ever strengthened the bosses. Every single pit in Nottinghamshire has been closed.

The clamour for a national ballot

The Tories and their kept media were engaged in a hue and cry about having a national ballot, echoed by the Labour leader and some right-wing union leaders. Some right-wing NUM local officials focused on this demand to hide behind as they advised members to cross picket lines.

This love of democracy was very selective, however. Back in 1974 and in 1977 national ballots had clearly rejected the implementation of area-based productivity bonuses, but the “moderate” area officials and the (then) right-wing national union leaders colluded to implement it anyway.

As for the Tories, this was all sheer hypocrisy. The bosses – the ruling class – never cared about democratic niceties when they were closing workplaces, or destroying jobs. No ballot was ever held to ratify those decisions. The bosses can ruin the economy, start a run on the pound, raise prices or crash the stock market to force any government to do their bidding – no ballot necessary! Thatcher’s love of democracy did not prevent her from supporting the military dictatorship in Chile or apartheid South Africa.

The right-wing Labour figures and trade unionists like Frank Chapple, of the EETPU, were just following on, acting in the interests of capitalism, which they supported. Chapple would later go on to form scab unions in the print industry.

The principle was that those pits that were threatened, 20 openly but over 70 in reality, demanded solidarity from other miners and the principle of solidarity was enough for most miners who were voting with their feet and going on strike. To halt this fighting spirit and to call off the strike while a formal national ballot was held would have been a diversion which would have demobilised and weakened the dispute just at the crucial stage when firm and resolute leadership was needed.

Police used to defeat the strike

By this stage of the dispute, an estimated 8,000 police a day were being drafted in from 41 out the 43 police authorities. They were openly siding with the bosses and the government. The law on so-called “secondary picketing” for example, which dealt with workers picketing workplaces other than their own, established it as a civil offence that employers could seek civil remedies for. But the police were preventing secondary picketing as if it were a criminal offence, often violently arresting pickets or preventing them from moving around the country. Many miners who had had illusions in they neutrality of the police were learning lessons fast.

Miners from St John’s colliery in South Wales tried picketing at Thorsby in Nottinghamshire, but were forcibly prevented from even talking to the working miners, as were miners from the pit itself. In response to a request for one police officer’s name and number, he replied, “Listen, son. I’ve got no number, no name and you’ve got no rights. So shut it!” [Militant 30 March]

Twenty miners were arrested at Cresswell in Derbyshire and one, John Dunn, was struck on the head from behind by police, receiving – eventually – three stitches. He was charged with a public order offence and bailed. Like so many arrested miners, his bail conditions stipulated – no more picketing!

Solidarity!

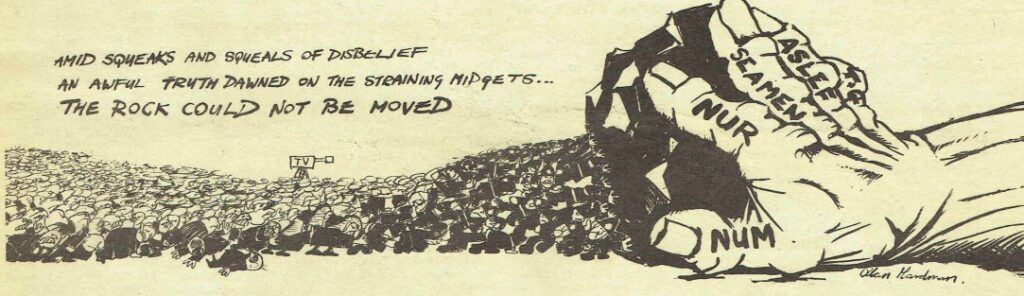

As ever, the key to winning was solidarity action from other groups of workers. The two rail unions – NUR and ASLEF – agreed to “black” (ie refuse to deal with), moving coal around the country, and local workers implemented that decision in the face of threats, harassment and injunctions.

At Ravenscraig steel plant the workers position was to accept coal to keep the plant open. Eventually a deal was struck to accept enough coal to keep the plant operational. Open-cast (ie non-pit, surface) miners in the Transport and General Workers Union, agreed to ensure their coal was not moved. It was reported that coke supplies to iron foundries were drying up.

In South Wales, bus workers threatened to strike after their bosses refused the NUM use of their buses to transport pickets, and the bosses backed down. Even some bus companies advised drivers not to cross picket lines, fearful of being boycotted by the community.

In the north of Ireland, branches of the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE), which is now part of UNISON, each agreed to adopt a pit to support.

But calls to national union leaders of steelworkers and rail workers to join the strike with miners in a triple alliance continued to be made.

Community and women’s support

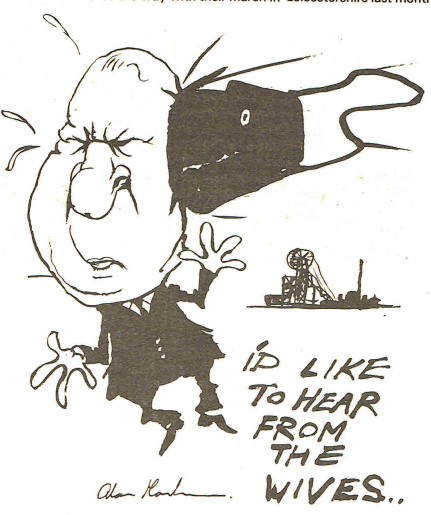

Ian McGregor (boss of the National Coal Board)

gets what he asked for

The role of women in the mining communities was becoming increasingly important during these first couple of months, both in providing food and in more political campaigning. Stories emerged of soup runs by women’s support committee to picket lines, such as in Whitwell and Bolsover in Derbyshire.

Women from the Kent mining community organised a trip to Coalville in Leicestershire, and a march through the town. They pointed out that no pit was safe.

South Yorkshire County Council took the decision that it would not meet the costs of any of its police that were deployed outside its borders and even schoolchildren in Yorkshire organised demonstrations and rallies in support of the miners.

Conclusion

Morale was high during this period as the strike call appeared to be heeded by more and more miners, and solidarity actions were being taken by other groups of workers. But the political and media obsession with a national ballot was a serious problem and the government were using the police to break the strike and keep mining communities divided.