Throughout this 40th anniversary year of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular bulletins on important issues and developments that occurred during the strike, month by month, as well as specific articles analysing major events.

This update deals with the period from 20 April to 18 May 1984.

*******

As the strike entered its tenth week and beyond, morale was still high. More pits and miners were joining the strike. But this was already a long and bitter dispute, marked by dogged determination in the face of relentless media hostility and intensifying police violence. Of course, nobody at this stage could know that the strike would not last just a few more weeks or months but a whole year.

The crucial issues, as ever, were spreading the strike and building solidarity action from other groups of workers. Meanwhile, support was increasing from women in the mining communities and the general public. Women were starting to play a more active role in organising the strike itself, including picketing.

Politics and Media

Thatcher and the Tory government were willing to fight to the end, although they, also, had no way of knowing how long it would last. They were adamant that at least 20 pits would close, with the loss of 23,000 jobs. In reality, they had secretly planned for much more severe cuts and the virtual destruction of the entire coal industry. The Tories’ savage cuts to benefits received by striking miners’ families, whether or not strike pay was received, was a deliberate attempt to starve miners back to work and mining communities were experiencing severe hardship as their savings disappeared.

The Tory Cabinet “Civil Emergency Sub-Committee” calculated that if the strike remained partial, they could carry on indefinitely, provided oil supplies were maintained and coal stockpiles could be accessed. If the strike became a total, full strike they estimates that they could hold out for 16-20 weeks. The Committee was considering the use of troops to move coal if it became necessary. [Militant 27 April]

The police operation alone was costing £1.5 million a day and one police officer admitted to working 150 hours of overtime in just 10 days! The government was happy to spend all this money for the principle of smashing the NUM. Yet in 1983 alone, £366 million had been paid out in interest charges by the National Coal Board, itself made up of members of the industrial and financial establishment. The money was there to run the industry well, even if you believed the fiddled statistics on “uneconomic” pits. [Militant 4 May]

On 25 April, the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party, to howls of media outrage and denunciation, voted to institute a 50p a week levy to support the miners and encouraged all trade unions to do the same. The motion was moved by the Labour Party Young Socialist rep on the NEC and was seconded by Tony Benn. This exposed the vacillation and cowardice of the leader, Kinnock, and the bulk of the Parliamentary Labour Party, as the press demanded that they denounce the decision.

Arthur Scargill himself explicitly said that the strike would “pave the way” to a Labour victory, making the political nature of the strike clear and further embarrassing Kinnock and the rest as they tried to strike a more neutral pose. [Militant 18 May]

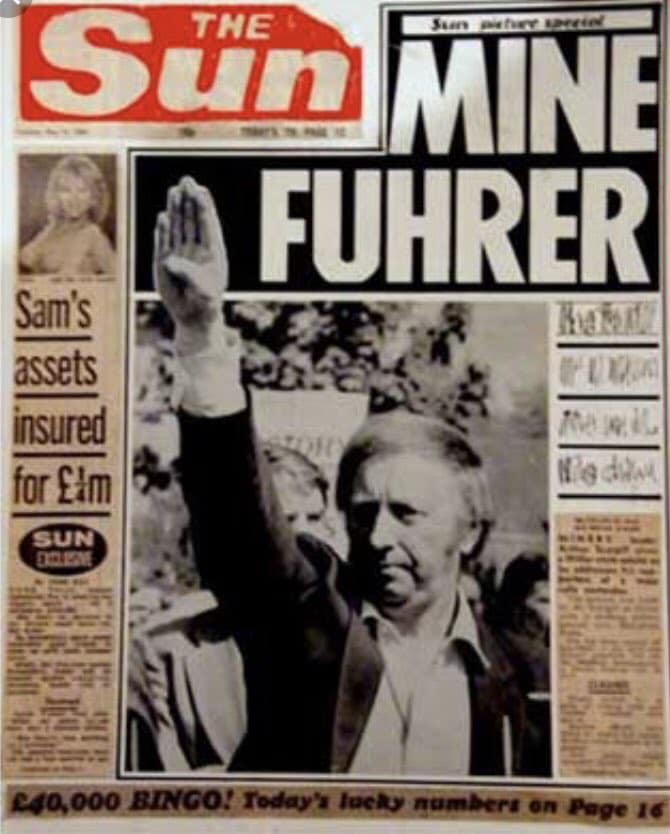

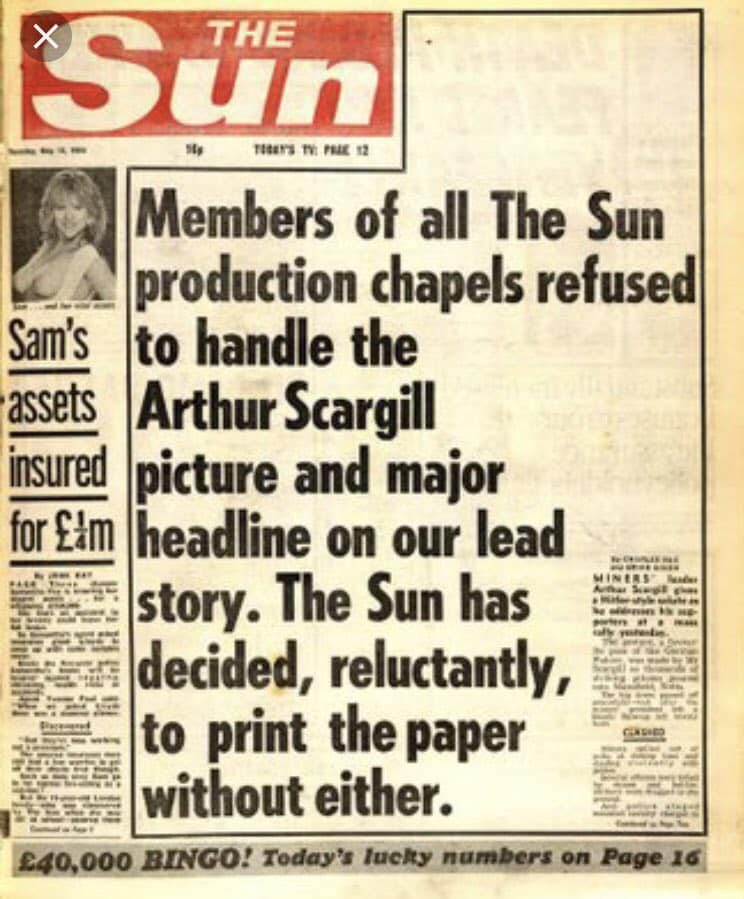

The media bias against the miners was despicable and the abuse of Scargill personally was appalling. Print workers at the Daily Express forced the paper to issue an apology to Scargill on one occasion but the most famous incident involved the most vile newspaper – The Sun.

On 15 May, it planned to print a front-page using a picture of Scargill waving to a crowd to suggest that it was a Nazi salute. It used the headline, “Mine Fuhrer!” in reference to the title used by Hitler. The printers and other workers refused point blank to produce the paper and it had to go out with a blank space on the front. This was great solidarity, but the relentless smear campaign continued throughout the strike and many years beyond it. [Militant 18 May]

More pits come out

Even at this late stage, groups of miners were joining the strike as well as individual pits – one by one! At Holditch pit, near Stoke, it was reported that only (!) 23 miners crossed a picket line and the miners shared their food with the pickets.

Miners from Sutton Manor and Bold collieries in Lancashire occupied the Lancashire NUM headquarters in protest at their not joining the strike call. In a real victory, the largest Lancashire pit, Parkside, near Newton-le-Willows, voted to strike in late April. Finally, the Lancashire area NUM officially joined the strike. At a rally on 12May 10,000 people marched through St Helens and some of the miners’ banners on the march were from pits that had been working just a few weeks before [Militant 18 May].

Women get organised

Women were continuing to organise meals for their communities who were facing increasing hardship. In Barnsley the Civic Hall canteen was given over to providing meals, supplied by local businesses and farmers and “Alice’s Bakery. At ‘Simco DIY and Food’ they made over their usual ‘charity corner’ to collections of food for the miners for three days. The local press said they had been blackmailed into it but the ship vigorously denied that claim.

But women’s involvement was going beyond food supplies. They were also taking a part in pickets. This happened at Sutton in Ashfield, for example. At Pye Mill No 2 pit, however, the local police inspector was not pleased and said that he would allow “no wenches” [sic] on the picket line, threatening women with arrest! [Militant 18 May]

A report from Gateshead outlined the links they made with women at Westoe pit in Durham, who formed a women’s support group. Another soon popped up in Ashington in Northumberland and then spread all over the North East. This story was repeated all over the different coalfields as women from the communities and other women supporters got organised.

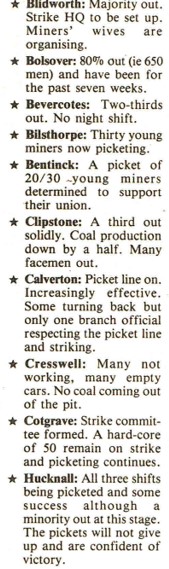

Nottinghamshire

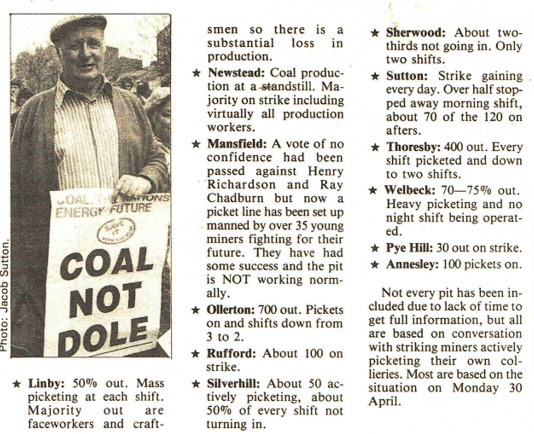

Nottinghamshire remained the biggest problem for the NUM. Throughout the strike, it was a complex and confused picture. Some pits were mostly on strike, others not. Some pits were bitterly split down the middle, as were the mining towns and villages and even some families. The images alongside this article give a rough snapshot of the situation in early May, pit by pit, regarding who was working and who wasn’t.

The media story was that Nottinghamshire was working almost normally but actually, between 10,000 and 12,000 miners were out on strike. The government’s own figures showed that in South Notts, the output was 50 percent down, while in the north of the area it was 60 percent down. 200 workers at Clipstone pit walked out after a mass meeting. A co-ordinating committee of striking miners was formed with delegates from 17 different Nottinghamshire pits.

There were still some stories of individual success, but relations had soured to such an extent that it was less realistic to expect picketing alone to bring more working miners out on strike. If there were to be any chance of bringing round the working miners, then a much wider and more ambitious campaign of persuasion would have been necessary from the leaders of the national union, with full workplace meetings, leafleting campaigns in the villages and so on.

But such a full campaign did not really materialise, and such was the bitterness by this late stage that it would have been met with stiff resistance from many working miners. In any case the unprecedented and oppressive police operation had made it virtually impossible to actually talk to any working miners, which was their plan all along, of course.

There was a demonstration addressed by Arthur Scargill in Mansfield, in Nottinghamshire, on May Day, as a counter to a march by working miners. Both had about 3,000 marchers but it was the working miners’ demo that got all the publicity, of course.

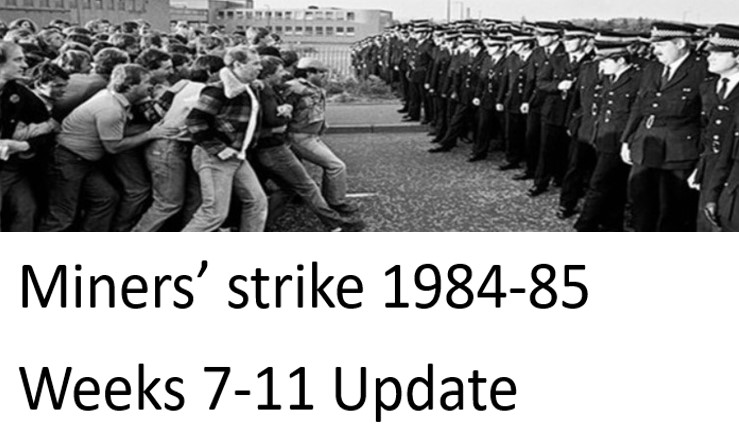

Police action – miners vs the state

The police had long since given up any pretence to fair or neutral policing. “Arrest the scum!” as one officer said outside Littleton colliery. At Bentinck colliery a picket who had their child with them was threatened the child being taken into “care”. [Militant 4 May]

Pickets at the Ravenscraig Steel Plant in Scotland were outnumbered 1,000 to 60! At Hunterston ore terminal in Ayrshire, pickets were badly trampled by police horses. A young miner was kicked full in the face by a policeman and was unconscious for ten minutes, while another, Davy Hamiliton, was gripped around the neck so tightly and for so long that he lost consciousness. [Militant 18 May].

At Bevercotes colliery, the police arrested pickets and interrogated them about how they voted, what they knew about Arthur Scargill, whether they had been approached by left wing socialists, and whether any “blacks from Liverpool” [sic] were on their way. They answered no comment to every question of course. [Militant 18 May]

Miners were routinely bailed on condition that they did not attend any Coal Board premises or picket. One previously non-political young miner from Kilmhurst, Graham Hague, was, indeed, radicalised by such treatment by the “paramilitary police” at Creswell colliery. He became a committed socialist! [Militant 18 May]. He was just one of a whole generation of young miners who became active in various strands of the Marxist left as a result of their participation in the strike.

At Tow Hall in Durham, the left-wing socialist MP for Sunderland North, Bob Clay, was arrested.

Solidarity Action

The rail unions continued to refuse to move coal stocks, in a great act of solidarity. Yet some of their own jobs in the rail engineering plants were threatened and could have formed the basis of their own separate dispute. This was an opportunity missed.

At West Thurrock power station in Essex, it was reported that no coal was arriving by road, rail or sea. Wyvenhoe docks in Essex saw pitched battles as pickets tried to stop coal imports. A picket at West Drayton coal depot in London closed it, at least for a while, and more picketing was planned for later. At Llanwern in South Wales an agreement was reached to only allow the minimum, emergency coal into steel plants to stop the furnaces from cracking, which would have shut the plant down permanently.

At Port Talbot in South Wales, the picket at the steel plant was joined by 200 students from local schools and tech colleges, defying their head teachers. As one boy told a policeman, “I’m furthering my education – I’m learning to be a picket, cos it’s the only job I’ll get round here” [Militant 27 April]

At Ravenscraig steel plant in Scotland, a compromise agreement allowing 11 train loads of coal per week was accepted by the NUM and the Steelworkers union, the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation (ISTC – now “Community”) on the condition that all foreign imports of coal would be blacked, ie not dealt with. The dockers’ union the Transport and General Workers’ union (TGWU) agreed not to unload any at the nearby Hunterston ore terminal.

When they tried to use casual, non-union labour to unload it, British Steel was forced to back down but it then agreed with a local official of the ISTC for steel workers to unload 68,000 tonnes of coal themselves! That official was disciplined by the ISTC but the whole incident threatened a dock strike unless clear undertakings were given that this would not happen again. [Militant 18 May]

Steel workers, rail workers and dockers were all facing attacks from their own bosses. United, co-ordinated action could have brought the Tory government to its knees.

[NB – many of the reports in this article have been taken from the newspaper Militant editions published in April and May 1984]