Throughout this 40th anniversary year of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular bulletins on features and developments that occurred during the strike, month by month, as well as specific articles analysing major events.

This update deals with the period from 18 May to 15 June, just before the important defining milestone of the “Battle of Orgreave” on 18 June [see our main Orgreave article here]

*******

The strike entered its fourth month during this period and as such, was a longer dispute than many had predicted. It was already longer than the strikes of 1972 and 1974 put together.

On 1 June, Brian Ingham, writing in Militant said: –

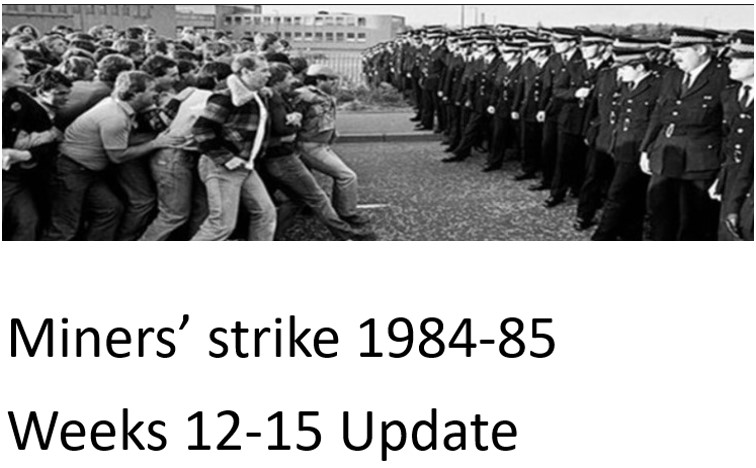

“This is one of the biggest ever struggles in Britain to save jobs, if not the biggest. Miners are being faced with unprecedented intimidation and brutality by the police, with riot shields, dogs, baton charges, mounted police, mass arrests and terrible financial hardships, all for the crime of fighting for their jobs and the future of their communities”

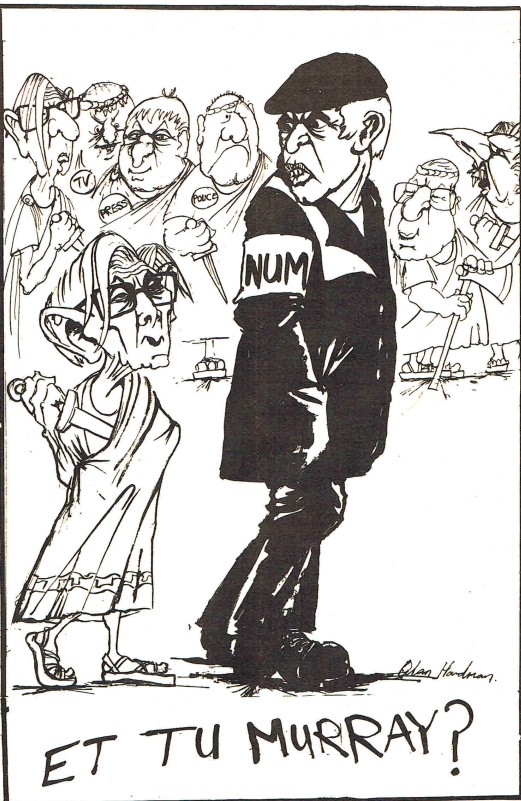

These weeks also provided a contrast between two trade union leaders. Len Murray, the General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress, resigned, aged 60, earlier than expected, to be later ennobled as Baron Murray of Epping Forest. Arthur Scargill, by contrast, was arrested on a picket line at Orgreave at the end of May, a few weeks before the more famous “battle” on June 18.

Talks

In early June, secret talks were being held between the National Coal Board (NCB) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) led by Scargill. There was the suggestion of a softening of tone by the Tories and the NCB bosses. The Guardian even reported (30 May 1984) that they were prepared to withdraw the immediate closures of 20 pits, in an effort to seem reasonable, while still keeping their future plans for pit closures intact. They were also offering higher wage incentives to the miners who remained after the closures.

They were undoubtedly testing the water to see if the resolve of the miners and their leaders was staying firm or whether some shady deal could be arrived at. The bosses wanted to exploit any divisions in the NUM Executive. There was talk of a “Special Conference” in July to decide whether to accept some new terms. Scargill’s answer was clear – “There will be no sell-out!”. There would be no agreement unless the pit closures plan was withdrawn by MacGregor and the NCB. No agreement was reached.

It was reported in the left press that some power stations were running perilously short of coal and that this would lead to some temporary power cuts. 55 out of 57 coal-fired power stations were said to be curtailing their output many by more than 50 percent. The proportion of oil used in electricity generation had risen to 33 percent from the normal 7.5 percent. It was costing £10 million per week to switch to oil from coal [Militant 25 May 1984]. One hopeful calculation estimated that that the coal stocks would run out by October 20 [Militant 8 June]

The cost to the government of the strike was estimated to be £75 million a week! The most recent balance of payments figures that were published in early June had the deficit at an enormous £838 million, mainly due to the massive purchase of imported oil.

However, it was also reported, on 15 June, that the Government had been stockpiling large amounts of coal in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, ready to be imported [Militant 15 June]. This intensified the bitterness at pickets of docks, such as at Wivenhoe in Essex.

Polish coal

One shameful episode, especially for supporters of the “Communist” Party, involved the importation of coal from Poland. This self-proclaimed “socialist” state had actually doubled its coal exports to the UK. On 18 May 1984, Dennis Skinner MP wrote to the ambassador of Poland protesting at this flagrant scabbing. But the bureaucratic clique in Poland had no concern for the miners in Britain, any more than they had for the miners in Poland and the exports continued. Such is the logical end point for so-called “socialism in one country”.

Attempts by the firm Powell Dyffryn Fuels to import German coal through Portsmouth was another focus for action. Six pickets from Abercynon colliery in South Wales were arrested (one of them for shouting “scab”). Thanks to the efforts of the members of the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU – now part of Unite) the coal was “blacked” (ie not moved or dealt with) and left stockpiled at the depot.

The background to Orgreave

At this time, the focus turned to the coking plant at Orgreave, in south Yorkshire. A deal had been struck between the NUM, the TGWU at Orgreave and the rail unions (NUR and ASLEF), to supply 15,700 tonnes of coal to the steel plant at Scunthorpe to preserve safe operating levels and prevent it from closing down. Blast furnaces need to operate continuously to prevent damage and permanent closure.

The deal was that the coal would be supplied from four Yorkshire pits provided it was moved by rail. If extra coke was needed for safety reasons, then it was agreed that it could be moved from the Orgreave coking plant by rail to Scunthorpe, if a request was made by the steel workers union.

From 15 May, it became clear that one of the blast furnaces was beginning to be in danger of collapse. This was actually due to coal being used to boost other furnaces, rather than keeping them all going equally. The “moderate-led” steel union (Iron and Steel Trades Confederation – ISTC) did not ask for a dispensation to move coal from Orgreave.

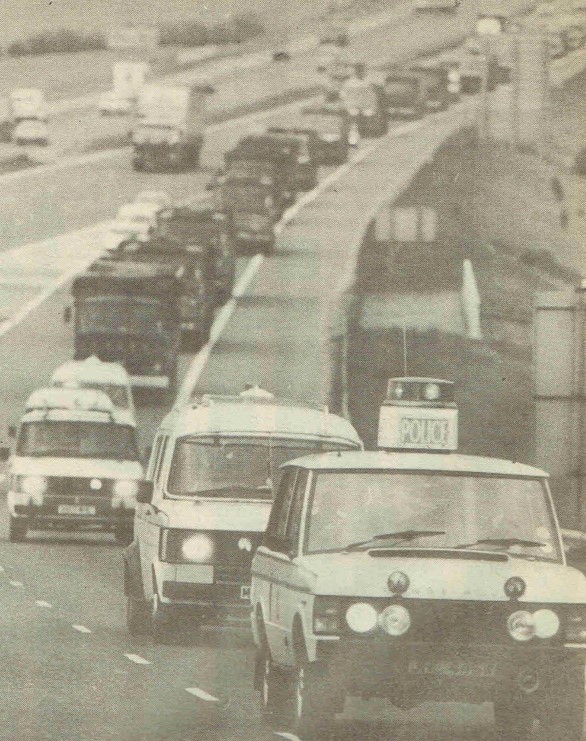

The British Steel bosses decided to move coal by road and on 23 May, scab lorries with massive police protection started to move coal to Scunthorpe. Yet a meeting between all the unions had already been planned for 24 May, which would have granted a dispensation!

This was a blatant attempt to take power from the unions and to drive a wedge between the steelworkers, rail workers and miners – the Triple Alliance. The bosses knew that using scab lorries would lead to complete “blacking” of coal shipments by the NUM.

Shocking violence

On 29 May the picket of Orgreave by the NUM, eventually 7,000 strong, was met with shocking violence – a foretaste of the treatment of miners on the 18 June. Local South Yorkshire police were kept back while those from other areas, together with sinister forces posing as police, were sent in with mounted baton charges on horseback using 4-foot (1.2m) batons.

One shocked local policeman told pickets “those bastards have been brought up from London. They’re up here to harm you. They’re nothing to do with us!” Another local officer said his dad was a miner and was picketing there. [Militant 1 June].

Another witness, Wendy Brown from Rotherham Labour Party Young Socialists, described it as

“…the most terrifying thing I have been through in my life. It was like something from Gdansk. What made it worse for me was that it was all happening in the village where I’d lived most of my life. Mounted police were charging in, swinging their batons wildly”.

[Militant 1 June]

Gdansk, of course, was the city in Stalinist Poland where brutal force had been used against shipyard workers in the new Solidarnosc trade union, fighting for freedom and a better life.

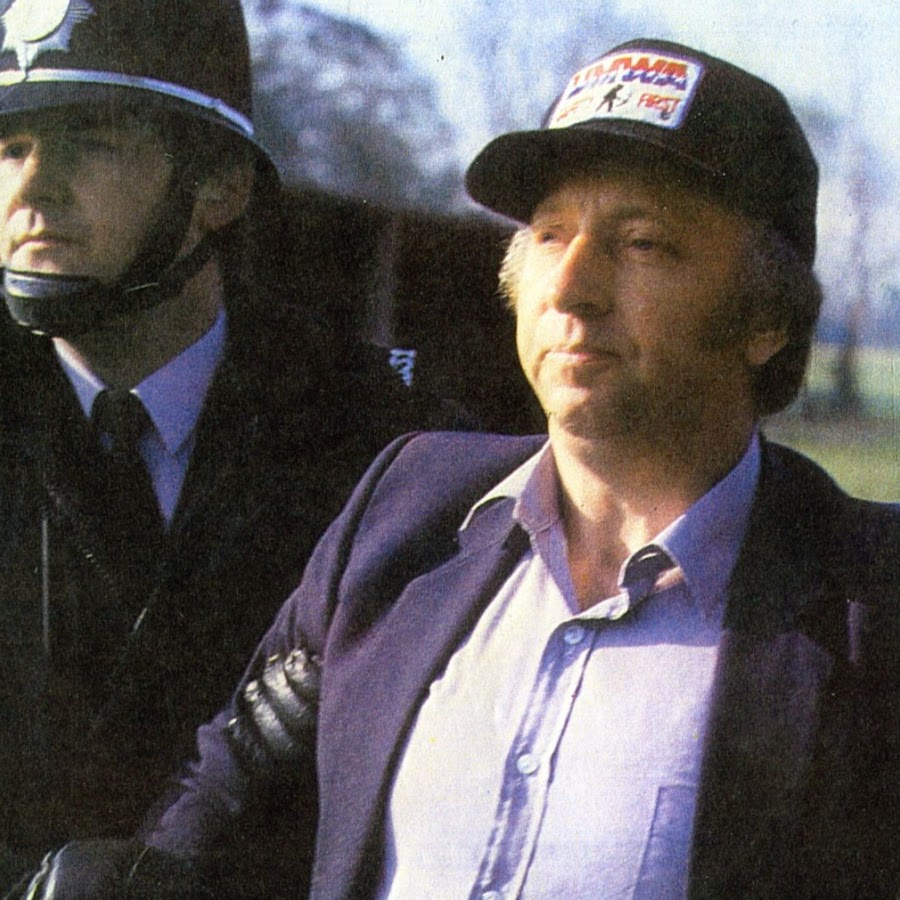

Scargill arrested

Yet, even in the face of such attacks, the pickets came back every day. In what could only be seen as a deliberate provocation, Arthur Scargill himself, the General Secretary of the NUM, was arrested on 30 May for “obstruction” while trying to organise pickets with a megaphone. The police requested stringent bail conditions to try to keep Scargill away from picket-lines, but, luckily, local magistrates granted unconditional bail.

The Assistant Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police, Tony Clement, described the incident as a riot! So miners running for their lives from mounted police was now a riot! That was an interesting use of language. But it was true that miners did begin to resist these attacks and fight back, rather than simply give in to this intimidation

Solidarity Action

On 21st May, the Yorkshire/Humber Trades Union Congress called for a day of action in support of the miners, up to and including strike action. The rail unions pulled out the signal workers on that day, causing major disruption to rail services in and around Yorkshire and to the east coast mainline. Not only that, the pit deputies (supervisors) came out on strike for a day, too. A rally in Sheffield attracted 2,500 people.

The national TUC General Secretary, Len Murray, tried his best to stop this solidarity gesture from Yorkshire – a final act of sabotage before his sudden retirement. In February 1985, while the strike was still going on, he was created Baron Murray of Epping Forest and toddled off to the House of Lords.

The National Ports Shop Stewards’ Committee voted for an all-out dock strike in support of the miners but the union did not pursue this. In a later day of action organised by the Northern Region TUC, several groups of workers walked out for a day, or half a day, in solidarity, including a half-day strike in the shipyards.

After a meeting addressed by the General Secretary of ASLEF, Ray Buckton and Jimmy Knapp of the NUR, the rail workers at Shirebrook rail depot in Nottinghamshire took the decision, in the face of threats and intimidation from their bosses, not to move coal for two weeks, . This was really significant, as Shirebrook was one of just a few rail depots that had not refused to move coal and it dealt with much of the scab coal from the Nottinghamshire area. This decision allowed pickets to focus on lorry transport, which was becoming the main method of moving coal to break the strike. In Liverpool, meanwhile, the socialist Labour Council voted to boycott any lorry firms that were involved in scabbing.

Miners from South Wales had been picketing the Didcot power station in Berkshire since early March, given food and Shelter from the nearby Ruskin College in Oxford and had received donations from workers at the British Leyland car plant at Cowley and local hospital and print workers. Didcot was now taken off the national grid!

A collection at the Scottish Cup final between Celtic and Aberdeen raised over £1,000 from football fans who chanted in support of the miners. In Scotland, 512 miners had been arrested between 14 March and 10 May.

All over the country collections were being made at street corners and workplaces. A miner from Cotgrave, Notts, reported that a pensioner donated £25 to the collection, and this was not an isolated example of sacrifice. [Militant 25 May]. Most areas had Miners’ Support Groups established to co-ordinate the efforts in particular areas.

Left wing socialist groups were making regular collections. The Labour Party Young Socialists, led by Militant made collections in most areas where it had a presence as did groups like the Socialist Workers’ Party. During the strike, hundreds of miners, especially the most active young miners were recruited to socialist politics and joined left groups.

London march and lobby

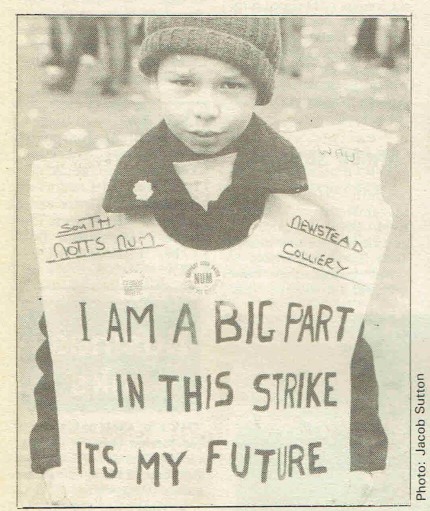

On 7 June a 30,000-strong march and lobby of Parliament was organised in London. It included, most notably, thousands of the most active young miners. There was a separate section of the march for women’s support groups, which were playing an increasing role in the organisation of the strike. Speakers included Betty Heathfield, one of the leaders of the Women Against Pit Closures, as well as Tony Benn, Dennis Skinner and of course, Scargill himself.

The march went down Fleet Street, which, back then, was the centre of the national newspaper industry, and miners made their opinions known! Printworkers from the SOGAT trade union, meanwhile, applauded the passing miners and handed them red carnations.

Of course, as expected, the march was roughly policed and fighting broke out. Many miners were arrested. One miner and his 9-year-old daughter were just looking at the police horses when he was arrested and she was reduced to tears. When the socialist Labour MP for Coventry, Dave Nellist, intervened, he was also arrested, and kept from seeing those who had travelled to lobby him!

Workers at Charing Cross and Waterloo rail stations walked out in protest at the violence meted out to the marchers by the police. When another miner was arrested, allegedly for a “breach of the peace”, and those who tried to rescue him were also seized, a section of the march refused to move until he was released, blocking several London buses. Once the bus drivers had been told what had happened, they took the keys out of their buses and refused to move until the miners were released – and an hour later, they were!

Women join the pickets

As well as continuing to organise canteen meals and food distribution, women were increasingly playing a part in picketing. Women at Cotgrave and Linby Support Groups in Nottinghamshire, for example, attended regularly [Militant 25 May].

The DHSS [now DWP] were assuming that miners were receiving £15 per week strike pay, but they knew this was not actually paid. Nevertheless, they deducted £15 from any benefits to miners’ families. No miners received benefits themselves, and as rent and rates [now Council Tax] were often deducted at source, some families were left with only 15p for a week’s food! It was grimly ironic that when miners were arrested and sent to prison, their families did get the £15!

Plans were being made to deduct further amounts from benefits if the family had received any donations of food, or gifts, loans or firewood. A family of a man and wife and two children would normally have received £61.80 but this was cut by £37.05. Labour Chesterfield Council set aside £50,000 for a miners’ hardship fund.

Women from Clowne and Barlborough Women’s Action Group (near Chesterfield) spoke to Militant [1 June]. Having got an empty shop by lobbying the parish council, they started providing breakfasts for children. One woman said: –

“We’ve fed the children at Easter for two weeks, and on May Day at the Youth Club, about 60 of them. Conditions are terrible for strikers and their families. I took a couple to the chemist for baby food; they both stood on the pavement crying because they were thankful to have had food for their baby. I ended up crying with them.”

In Ashington, in Northumberland, the Women’s Group had to move to bigger premises to deal with the numbers needing. But the women were determined not to give in. Pat Maughan said, “we are more comfortably off than our grandmothers were, so we can sail through this one.” They were organising a gala day and a disco for the children. [Militant 8 June]

Women were being radicalised. Pat Davies in North Warwickshire said: –

“I’m 47 and a grandmother. I’ve respected the police right up until now and the turnabout amazes me. When I look back 12 weeks ago, I was such a different person…

“I was influenced by the newspapers against the Labour left – that’s another thing that’s changed. I don’t believe what I read in the papers now because I’ve seen them as completely one-sided. I feel like I’ve been running around blind all my life…

“We’ve had to help others…There are young ones getting nothing at all – the single lads who’ve paid the most tax and stamps [NI]…I’m so proud of the younger ones. They’re saying ‘we’ll take these hard few months, even if it takes a year, because it’s better than losing our jobs forever.”

[Militant 8 June]

They didn’t know then that the strike would indeed last another nine months – a whole year in total – a titanic struggle that could have succeeded but would ultimately end in defeat.

[Much of the material for these articles comes from the socialist newspaper – Militant]