By Joe Langabeer

The arts have long been associated with the rich and have become a symbol of gatekeeping philanthropy.

The Hay Festival, the largest literature-focused event in the UK, was at the centre of controversy in 2019. The festival’s main sponsor, the Indian conglomerate Tata, was accused of harming poor communities in India and restricting their rights. After this came to light, Tata withdrew its funding. The festival then found a new sponsor, the Scottish asset manager Baillie Gifford, which manages over £225 billion in assets and is well-known for being an early investor in Elon Musk’s Tesla.

However, it was later revealed that Baillie Gifford was profiting from fossil fuels and channelling money into Israel’s occupation and the conflict in Gaza. In response, many authors, including Grace Blakely, promoting her book “Vulture Capitalism,” withdrew from the festival in protest. Due to pressure from the Fossil Free Books campaign and authors’ withdrawal, the Hay Festival ended its sponsorship with Baillie Gifford, and the asset manager announced it would no longer fund UK literary festivals.

This situation highlights the influence that capitalism and philanthropy have over the arts. Still, it also raises questions about who the arts are currently meant for and how we can change this for the future.

As described in the Financial Times, the recent Hay Festival controversy has caused concern among artists, with investors and philanthropists for other arts organisations indicating a potential hesitation to continue philanthropic investment in the UK. This hesitancy stems from fears of public criticism over associations with ecological disasters or support for states involved in apartheid.

Michael Moritz, a tech investor and sponsor of the Booker Prize, has remarked that philanthropic backing for the arts may be paused unless there is a display of “calm and resolute minds.” This reaction has been perceived as an overreaction by some, particularly in discussions on platforms like X (formerly Twitter), which the FT article suggests is a contributing factor to investor withdrawals from art festivals.

Capitalist sensitivity

The sensitivity of the capitalist class to such challenges is worth considering. If they recognise the adverse impacts of their associations, why do they continue making these investments? Perhaps it is to reinforce the established norms of capitalism, imperialism, and genocide by supporting their allies.

Companies retracting their support from artistic endeavours, such as bands, singers, and UK music festivals sponsored by Barclays, due to alleged ties to the defence industry of Israel is not a novel occurrence. What stood out this time was how Fossil Fuel Books’ relatively tame activism pushed Gifford to pull out of funding so quickly. Despite limited social media support, they only called on Baillie Gifford to divest away from oil and gas companies and to cease financing Israeli genocide in Gaza. Gifford’s hasty withdrawal of funding from festivals reveals that their priorities lie more in maintaining their brand image than valuing artists at the festival.

After Gifford withdrew funding from the festival, there has been a strong reaction from supporters of the London Metropolitan establishment. Guardian columnist Marina Hyde, who argues that Corbyn, Johnson, and Farage are all the ‘same’, criticised ‘activists’ for their response to the funding issue at the Hay Festival in her podcast ‘The Rest is Entertainment’. She also suggested that “politics should be separated from art.”

Not all art needs to be political; this is true. Art can embody various values, some of which are deeply emotional and can be appreciated by the working class. In a pamphlet from Trotsky in 1923 entitled “Communist Policy Toward Art,” the importance of this notion is underscored.

“What the worker will take from Shakespeare, Goethe, Pushkin, or Dostoyevsky will be a more complex idea of human personality, of its passions and feelings, a deeper and profounder understanding of its psychic forces and of the role of the subconscious, etc. In the final analysis, the worker will become richer.”

Political art structures

Not all art is political, but the way it’s currently structured is inherently political. The arts are heavily influenced by capitalist funding, often resulting in art that caters to the establishment rather than the general public.

Various forms of philanthropy play a significant role in the arts. For example, the National Theatre in England, which is widely regarded as one of the UK’s leading theatre venues, is sponsored by Edwardian Hotels London, a major global hotel chain. The owner of this chain, Jasminder Singh, has been a generous donor to the Tory party in multiple general elections, as reported by Left Foot Forward. This creates a conflict of interest, especially considering that the National Theatre receives substantial funding from the government and Arts Council England (ACE). For instance, in the 2024 Tory spring budget, the National Theatre was granted a £26.4 million capital investment for building renovations.

This dual funding approach raises questions about the allocation of resources, as the theatre seems to prioritise vanity projects over supporting emerging playwrights and showcasing more radical work due to the fear of losing government and investor support. The Arts Council is also culpable to the defence of the Tories. Earlier in 2024, they issued new guidelines stating that any “political statements” from performing arts companies or individuals within the companies could lead to a breach of the funding agreement. However, they also emphasised the importance of “freedom of expression” in their clarification.

The Arts Council has historically been used to suppress political art, especially during the 1980s when funding was cut for art groups that challenged the establishment. This was exemplified when William Rees-Mogg took over the council and enforced a more hierarchical structure and management culture. The current system of the Arts Council of England isn’t working and has been influenced by the Tories and defenders of capitalism.

BP and the Tate

Another highly publicised incident of capitalist funding in arts institutions was the Tate, which had a 17-year partnership with BP. During this time, the Tate received a total of £3.8 million from BP, averaging £224,000 annually. In 2023, BP ended its partnership with the Tate, citing a challenging business environment for continued investment. BP has partnerships with other prominent institutions such as the Royal Opera House, the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Royal Shakespeare Company.

The Tate responded to the end of the partnership by highlighting it as the most significant corporate investment in UK arts and culture. However, critics, including the activist group Liberate Tate, pointed out that BP has one of the worst records for CO2 emissions.

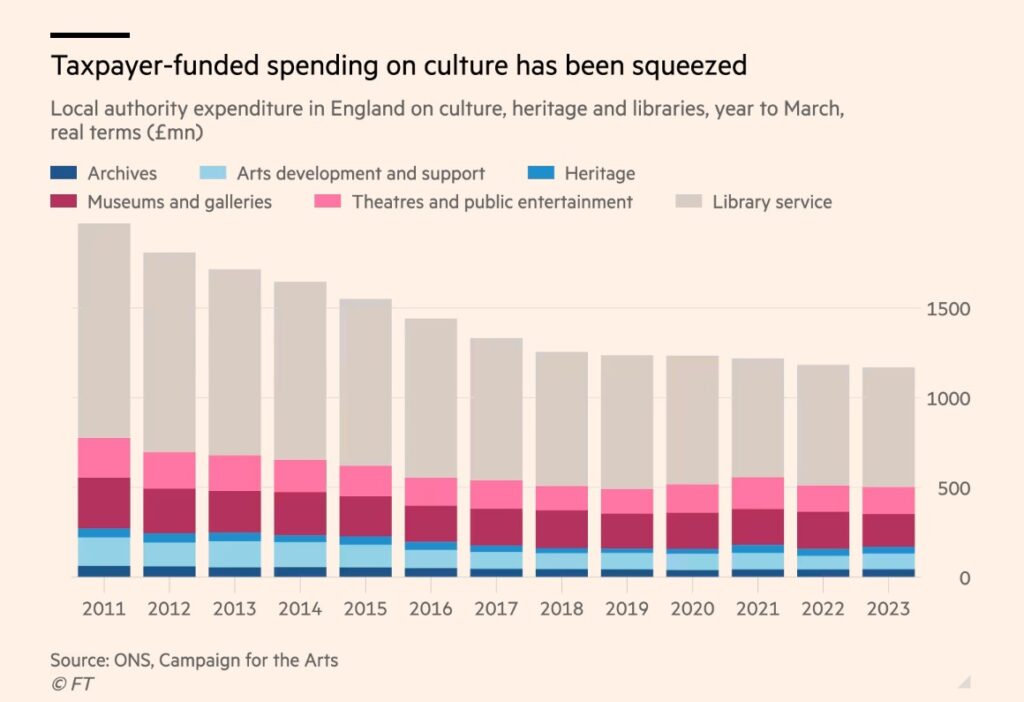

Many institutions, including the Tate, have increasingly relied on corporate sponsorships and philanthropic donations, potentially compromising artistic freedom. Furthermore, government funding for these institutions has been squeezed by local authorities, while some companies are also appealing for more investment. For instance, the English National Opera warned that it would face administration within twelve months if it could not find a more affordable home in which to produce work. However, that issue was currently resolved when they relocated to Manchester.

Depending on subsidies or philanthropy is not a sustainable way for arts to thrive. There should be a demand for a hands-off approach to making art and culture while preventing funding from dodgy philanthropists or subsidised organisations that dictate that work cannot be political.

Theatre venues, exhibitions, galleries, opera houses, museums, and libraries should be placed under public ownership, with laws to collaborate with independent artists to create various works, not just work that the state values alone. The arts are for everyone, and there should be a diverse range of work that intellectuals and workers can enjoy.