Throughout this 40th anniversary year of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular bulletins on important issues and developments that occurred during the strike, month by month, as well as specific articles analysing major events.

This update covers the period between the Battle of Orgreave (18 June) and 20 July.

*******

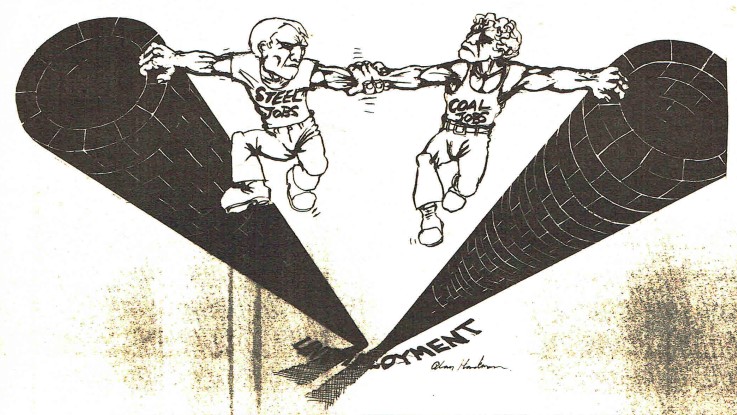

The most significant development during these weeks was the outbreak of the national dock strike, which gave great hope and encouragement to the mining communities and to workers generally. But, sadly, relations between miners and steelworkers and their union, the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation (ISTC), declined further over disputes around supplying enough coal to prevent furnaces from shutting down.

The two issues were actually closely related. Although the dockers had their own grievances, their decision to finally come out on strike was prompted the use of scab labour to unload and transport iron ore to Scunthorpe steelworks from the nearby Immingham docks, near Hull.

The issues around supplying coal and iron ore to Scunthorpe were already a source of controversy, and had led to the efforts to close down the Orgreave coking plant from which coal was being transported by scab lorries to Scunthorpe. The brutal attack on miners at the Battle of Orgreave had led to these pickets being called off (see the separate article on Orgreave here).

Rail workers had been refusing to move coal, except with the NUM’s permission, since the strike began. The government had not challenged them on this for fear of provoking an all-out rail strike. The National Union of Railwaymen, in late June, took a major turn to the left, endorsing a wide-ranging, full socialist programme, and pledged their support for the miners.

There was widespread support from many steelworkers for the miners, who had shown some solidarity, back in 1981, when the steel workers were attacked by MacGregor, the same man now trying to destroy the coal industry. Generous collections for the miners were being held at every steel plant. But the steelworkers had been beaten, plants had been closed and the workers had become demoralised. Their union, the ISTC, was traditionally moderate, and had not put up an uncompromising struggle three years earlier.

Steelworkers terrified of job losses

Now, having lost 50,000 jobs, steelworkers were terrified of losing the jobs that remained. A deal was vitally necessary to guarantee enough coal to prevent steel plants from being damaged by shutting down. Steelworkers could have agreed to reduce output in return for a pledge from miners and rail workers to fight alongside them to resist any further cutbacks or job losses – but the confidence among the steelworkers was just not there and their own “moderate” or “realistic” leaders were not doing much to inspire or lead them. The Tory strategy of picking off weaker unions first had paid off handsomely.

The result was increasing conflict between picketing miners and steelworkers. In some areas this became very bitter. There were even violent clashes between them at the Ravenscraig steel plant in Scotland. Some steelworkers were being paid “production bonuses” of between 10 and 20 percent!

The bosses at British Steel did all they could to weaken solidarity between the two groups of workers by using scab labour as a provocation – to break the negotiated deals between the unions to provide the minimum necessary amounts of coal and iron ore. As workers fought each other, the Tories could hardly contain their glee.

If only the miners, rail workers and steelworkers had joined forces in concerted joint strike action, alongside other worker such as dockers, they would have been unbeatable and the Tory government could have been defeated. But the TUC steel committee decided not reduce steel production during the strike and the golden opportunity was squandered. Instead of organising to win the strike, the TUC leaders saw themselves simply as “arbiters”, trying to end it.

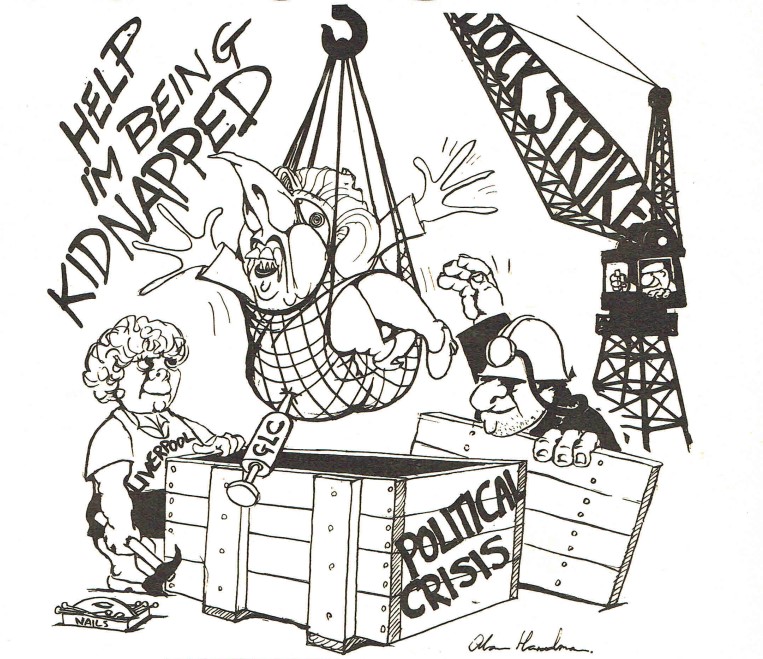

Dockers strike

But then, in early July, a dock strike started, giving a huge and much-needed boost to the morale of the striking miners. As a result of the train drivers’ union, ASLEF, refusing to cross the miners’ picket line at Immingham Docks to transport iron ore to Scunthorpe steel works, the steel bosses and the port employers decided to use scab labour to load lorries. 27,000 tonnes of iron was transported to Scunthorpe – enough to last until September. But, in doing this, they were also ripping up long-standing national agreements with the dockers. The dockers came out on strike!

There had already been disputes over pay and the threat of redundancies, and this attack was seen as a threat to the National Dock Labour Scheme (NDLS) which had ended the job-insecurity of dock work and was seen by dockers as central to maintaining their conditions of life. They had already forced a government climbdown in 1980 over the same issue. The dockers demanded cast-iron guarantees that the labour scheme would be preserved.

During this period, the dock strike was solid and even dockers in unregistered ports outside the NDLS, such as Lowestoft in Suffolk, wanted to join in. Barely any ships moved without permission [Militant 13 July], even in unregistered ports. The strike was strong in Tilbury, near London and in Liverpool, a local transport workers union (TGWU) official, a young Len McCluskey, said:

“If the government destroy the Scheme, then ports like Liverpool will be wiped out…That’s why in Liverpool we are all out…Dockers here are very, very determined indeed!”

[Militant 13 July]

A week into the dock strike, it was more solid than before. Felixstowe was out. In Southampton the dockers accompanied every customs official to check that no freight was being carried! [Militant 20 July]. The Tories were sent into a panic, and dark hints were made about declaring a “state of emergency” or using the troops to break strikes. But they feared provoking the trade unions into a wider industrial conflict, or even a general strike.

“The most inept government since the war”

The miners’ strike was now costing £65 million per week, and the cost so far, of £1 billion, would reduce growth in the economy from 3 percent to 2 and push inflation up to 6.5 percent. The Economist [7 July] described Thatcher’s government as “the most inept since the war.”

The government had been forced to come to a settlement with the Militant-led Liverpool Council – providing the equivalent of £55 million of extra funding – as a way of buying time and focusing on defeating the miners.

Labour MP, Dennis Skinner, speaking at the Durham Miners’ Gala, said: –

“The miners are out, the rail workers are out, now the dockers are out and very soon the Tories will be out.”

[Militant 20 July]

The well-known Labour left MP Tony Benn, who had recently won a by-election in the mining area of Chesterfield, in North Derbyshire, had spoken, at the end of June, about widening and generalising the strike action: –

“Trade unionists in a whole range of industries and services should plan to take industrial action where they work. No-one need wait for permission to begin. An extension of the strike action would directly assist the NUM and give them a tremendous moral boost”.

[Militant 29 June]

He called for Labour to lead a national campaign of meetings, rallies, fundraising events and a national demonstration to support the miners.

Meanwhile, the NUM started picketing the Polish Embassy in protest at the “socialist” state increasing its coal exports to help to break the strike – some 500,000 tonnes in total!

Paramilitary techniques

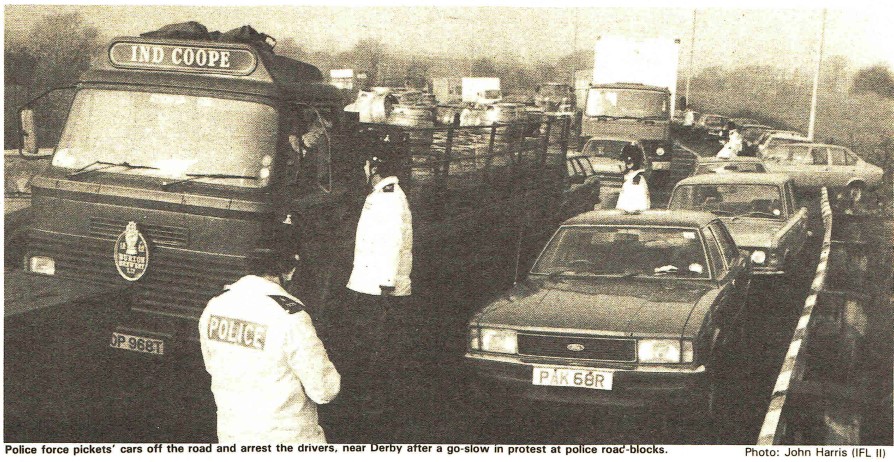

A review into policing of the strike “A State of Siege – policing the coalfields in the first six weeks of the miners’ strike” by Susan Miller and Martin Walker found that a new National Riot Force had been created from special units from all over the country, trained in paramilitary techniques and under the control of the National Recording Centre. That had been set up in 1972 by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) and it had no statutory authority and did not report to any of the local democratic police committees.

Under the direction of this body, police were routinely exceeding their legal powers, arresting people for “suspicion” of going picketing, preventing entry into a particular county, and using “catch-all” offences such as “obstructing a police officer” or “breach of the peace” to randomly arrest pickets.

They would then be rushed past magistrates and bound over, usually with conditions attached – typically, no longer attending picket lines. While under arrest the miners or their supporters would be interrogated about their politics or details about the organisation of the strike. Engineers working for British Telecom confirmed that phone tapping was widespread [Militant 29 June].

[photo AP]

The recent Tory anti-union laws allowed employers to sue the unions in civil cases over any breaches. Yet the police were using these laws as if they were part of criminal law and arresting any miners that they judged to have fallen foul of them. At Point of Ayr colliery in North Wales, police claimed that the picketing was illegal as the strike was “not official”. And the Tories were planning new laws on secret ballots for strikes and for electing the union leaders, as well as placing more restrictions on unions’ political funds.

State repression

George Moores, the Chair of the South Yorkshire Police Committee, like many others, was reduced to a bystander. He told Militant: –

“If I had to sum up what was most worrying, I would say that it is the concept of national policies that are carried out by police officers, without any legal standing whatsoever. Here we have state repression against people who are on the whole most moderate in their attitudes.”

[Militant 29 June]

Just one example illustrates the situation. On 9 July in the mining village of Fitzwilliam, South Yorkshire, the police sent officers to bring in “for questioning” Brendan Conway, a “picket captain” and the chair of the local Labour Party Youth Section. He insisted on seeing a warrant and the police went off to fetch one. Meanwhile a crowd of 200 had gathered around Brendan’s house and then moved off to the nearby Hemsworth police station.

A local NUM official negotiated a deal and the crowd dispersed, but back in Fitzwilliam a massive police presence of around 100 officers was patrolling and intimidating residents. They finally raided the local pub and other addresses, arresting Brendan and eight others, battering and injuring some of them, leading to a battle on the main estate between local youths and the police. Yet after all that, those arrested were only charged with a “breach of the peace” and were subject to a 7pm to 7am curfew.

The police then returned the following Friday and raided the pub again, arresting 18, and attacking and hospitalising people, including some who just happened to get in the way, who had no connection to the strike. One young man who had previously broken his arm had it twisted behind him, causing further damage to the break. Crowds formed of 150-200 people to resist these attacks, and a campaign was formed to protest at the police brutality. More and more miners were prompted to get actively involved in picketing.

[photo John Harris IFL]

Four women from Coventry Labour Party, who were responsible for 10 children, including babies, were arrested for “obstruction of the highway” – i.e. crossing the road! They were held for 15 hours instead of the normal 2-3 hours for an offence which would only be punished by a £50 fine, while they were quizzed about their politics.

Meanwhile, the Coal Board was stepping up its victimisation, sacking miners involved in protests. In Betteshanger Colliery in Kent, in response to claims by management that the pit was becoming unsafe and vulnerable due to the strike, 30 miners had occupied it from 17-20 June to carry out their own inspection, ratified by local management, which disproved the claims. On 26 June, they were all sacked! These claims were just one example of a tactic increasingly used all over the country to frighten miners back to work.

A Coventry miner, Clive Ham, who had been arrested along with his baby son, was sacked because of charges connected to that arrest, even before the case went to court! Even two kids in Gateshead were sacked from their paper round for delivering leaflets supporting the miners!

Women’s support groups all over the country

By this stage, growing from the first few at the beginning of the strike, there were hundreds of women’s support groups all over the country. These were still mainly focused on providing food for miners and their families and helping them cope with the increasing hardship. Four months into the strike, some miners were able to negotiate a pause in their mortgage or rent payments but unpaid gas and electric bills had started to mount up. However, the women’s support groups were also involved in picketing and organising the strike.

Brenda Arnold of the Birch Coppice Support Group in Warwickshire told Militant [13 July] that: –

“I hadn’t done anything like this before. Now I’ve been threatened twice by the police. First time was on the picket line at 5 in the morning…The second time was in the Birmingham Bullring Shopping Centre. We got a very good response from the public, especially pensioners and blacks. I hadn’t been to Birmingham for years…The police tried to hassle us…there were only five of us “begging”: two wives, two miners and a child of 14…We’re getting an excellent response. I’ve been round factories talking to shop stewards.”

Women from the Tiveton Park Women’s Action Group said it had been going since April. There was already 26 percent unemployment in the area, so that explained the community support for the miners, whether miners’ wives or not. Their top priority was to help “single lads and the under 5s”, as the single miners got nothing by way of benefits and under-fives didn’t get school meals.

“Above all we have met people through the struggle everywhere and got great bonds that will not be broken.

“We’ve been doing things we would not have dreamed of a few months ago. Girls who have never spoken in public before, have been speaking everywhere, from colleges to trade union bodies and getting support. We have been on every major rally up and down the country. We have also been on picket lines and were at Orgreave when the first police confrontations occurred. We have learned lessons that we will never forget…”

[Militant 13 July]

Public support

Public support for the miners, especially financial support, went from strength to strength. Thousands and thousands of pounds were now being collected every week, seemingly in every high street, in sporting venues, workplaces, union branches, and Labour and socialist groups. International solidarity was also impressive as truck-loads arrived from abroad. Money also poured in from different ethnic communities and religious groups. And on 30 June, a collection was held at the Lesbian and Gay Pride march in London, and this led to the founding of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners on 15 July (see separate article here).

This outpouring of popular support was not properly channelled and led by the leadership of the main unions or the Trades Union Congress. But the rail workers, and now the dockers, were showing the path to victory – determined joint industrial action to fight the government head on.

[Much of the information in this article comes from the socialist newspaper Militant issues from 29 June-20 July 1984]