By Michael Roberts

This blog was originally published by Michael Roberts on Thursday, 1 August 2024. The original article can be found here.

**************

At yesterday’s end July meeting, the US Federal Reserve Bank held back from cutting its policy interest rate from the current high of 5.25-5.5%. This was despite recognizing that the US economy was ‘cooling’, unemployment was starting to rise and economic activity was weakening.

The problem for the Fed was, as always, the balance, on the one hand, between keeping the cost of borrowing high in order to drive down inflation and on the other hand, against the risk of high borrowing costs causing households to reduce spending and businesses to cut back on investment and employment.

The Federal Reserve’s ‘dual mandate’

The Fed, like other central banks in the major economies, has got an arbitrary (and rather pointless) price inflation rate target of 2% a year; but unlike other central banks, it has a ‘dual mandate’ to try preserve employment and economic growth as well as getting inflation down. Can the Fed achieve this dual mandate? The Fed likes to claim that it will; also the consensus among mainstream economists is that it will achieve this ‘Goldilocks scenario’ of low inflation and unemployment alongside moderately solid economic growth.

But if the dual mandate is achieved it won’t be down to the interest-rate policies of the Fed. As I have argued several times before, monetary policy supposedly manages ‘aggregate demand’ in an economy by making it more or less expensive to borrow to spend (whether as consumption or investment). But the experience of the recent inflationary spike since the end of the pandemic slump in 2020 is clear. Inflation went up because of weakened and blocked supply chains and the slow recovery in manufacturing production, not because of ‘excessive demand’ caused by either a government spending binge or ‘excessive’ wage rises or both. And inflation started to subside as soon as the energy and food shortages and prices ebbed, global supply chain blockages were reduced and production began to pick up. Monetary policy had little to do with these movements.

Inflation remains ‘sticky’

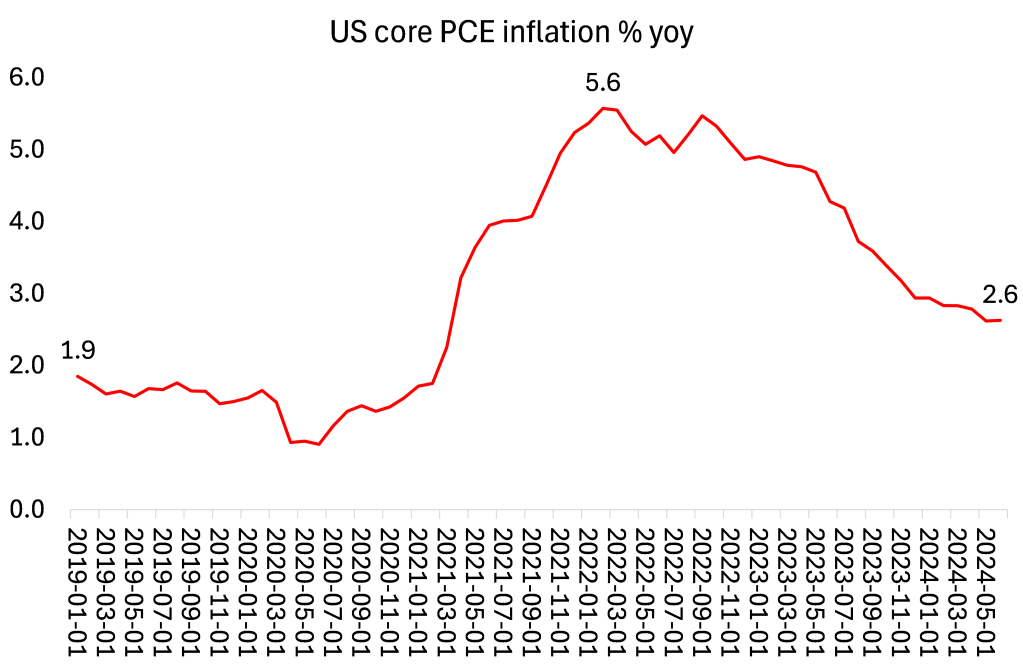

And contrary to the hopes and expectations of Fed chair Jay Powell and all the mainstream economists, there are trends in the US economy that suggest the dual mandate is unlikely to be achieved. First, inflation remains ‘sticky’ i.e. well above the target 2% annual rate. The Fed likes to measure US inflation based on the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index. This is a convoluted measure that excludes production prices and energy and food prices – hardly an accurate measure of price rises for the majority of Americans! Even so, the core PCE currently stands at 2.6%, down from a peak of 5.6% in 2022, but still well above 2% and the rate in 2019.

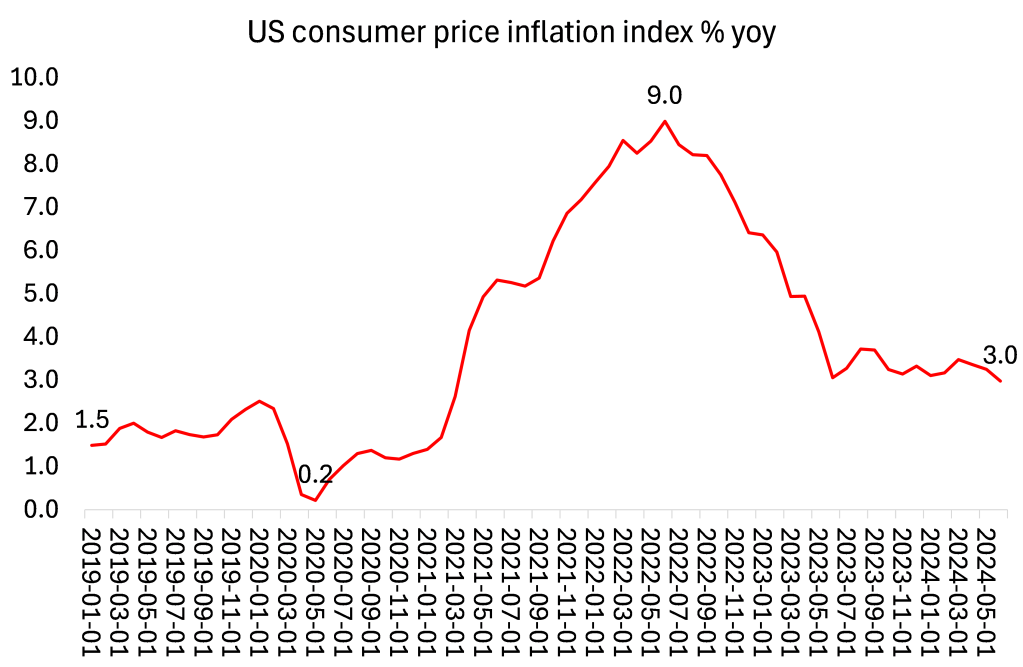

The overall consumer price inflation rate is much higher than the Fed’s measure. It currently stands at 3.0%, down from a peak of 9% in 2002, but still one full percentage point above the Fed’s illusive target and double the rate in 2019.

And as you can see, the CPI rate seems to be sticking around 3% with little sign of a further reduction despite the optimistic talk of the mainstream economists. The reasons are clear to me. First, as I have argued before and above, inflation has been driven not by ‘excessive demand’ but by weak supply ie low productivity growth and high commodity prices. Second, the prices of many products in the US economy have been hiked sharply over the past two years that it appears do not seem to affect the official price measures.

Big rise in the cost of housing, health insurance and car insurance

In particular, these include housing costs, health and motor car insurance, which have risen sharply. As a recent FT article admitted: “Both are partly a product of pandemic supply shocks — reduced construction and a shortage of vehicle parts — that are still percolating through the supply chain. Indeed, dearer car insurance now is a product of past cost pressures in vehicles. Demand is not the central problem; there is little high rates can do.”

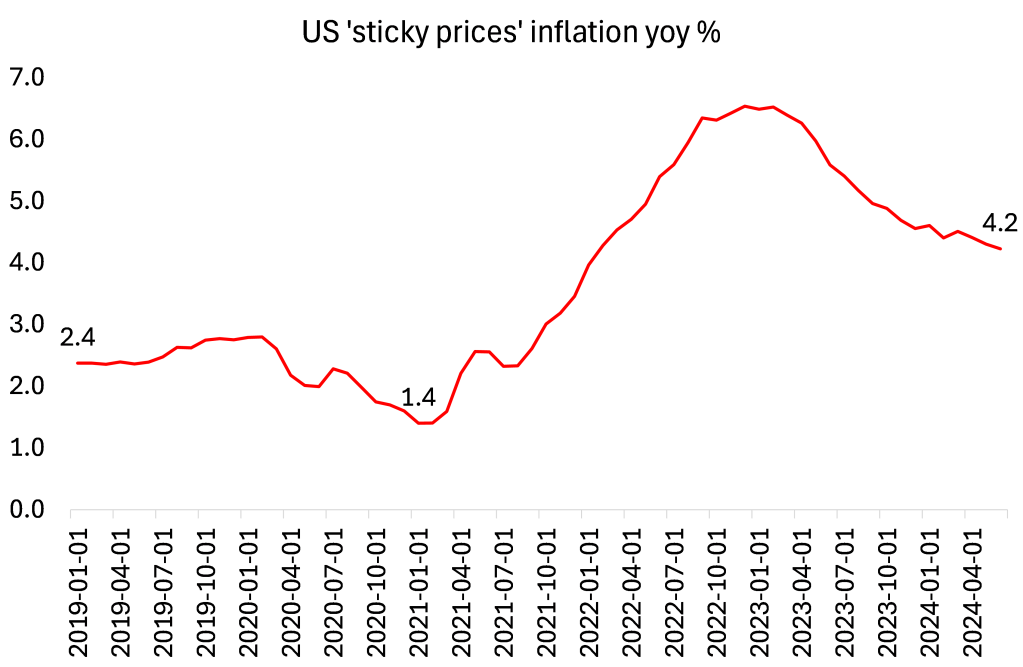

There is also another measure of inflation in the US economy called the Sticky Price Consumer Price Index (SCPI), which is calculated from a subset of goods and services included in the CPI that change price relatively infrequently -so not affected much by changes in demand. This index again shows a much higher rate of inflation, currently at 4.2% yoy, three times higher than in early 2021.

This measure suggests that inflation has become embedded in the economy with firms using any opportunity to hike prices but taking no opportunity to lower them. Don’t forget that American households have suffered an average 20% rise in the prices of goods and services that they buy over the last three years -so all that current slowing inflation means is that prices are still up hugely, but now not rising as fast. This inflation of prices has eaten into the real incomes of most Americans over the last few years so that even if they all have jobs (mostly low-paid services jobs), living standards have gone backwards.

So contrary to the Fed’s talk, the ‘war against inflation’ has not been won. As a result, the Fed has still not cut its policy rate. But in not doing so, the Fed’s high policy rate keeps borrowing rates high and so hits the profits of particularly small companies that often must borrow to invest and employ; as well as credit card and mortgage rates for households.

Is the US economy really motoring along?

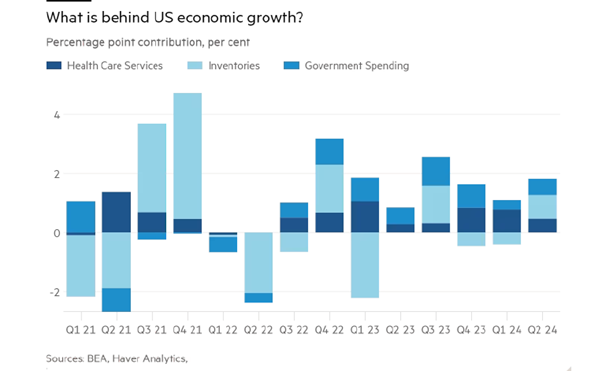

That raises the question of whether the US economy really is motoring along and so will avoid any downturn caused by the squeeze on profits from high interest rates. Much has been made of the recent advanced estimate of US annualized real GDP growth in the second quarter of this year at 2.8%, up from 1.4% in the first quarter. But this headline figure hides a lot of holes.

First, it is an ‘annualised’ rate, meaning that the quarterly increase in real GDP in Q2 was actually only 0.7%. Second, the headline rate includes major contributions from: healthcare services (0.45 percentage point); inventories (0.82 percentage point); and government spending (0.53 percentage point). Healthcare services are really a measure of the rising cost of health insurance not better healthcare and that cost has rocketed in the last three years. Inventories means stocks of goods unsold, in other words, output without sale; and government spending was mainly for arms manufacturing, hardly a productive contribution.

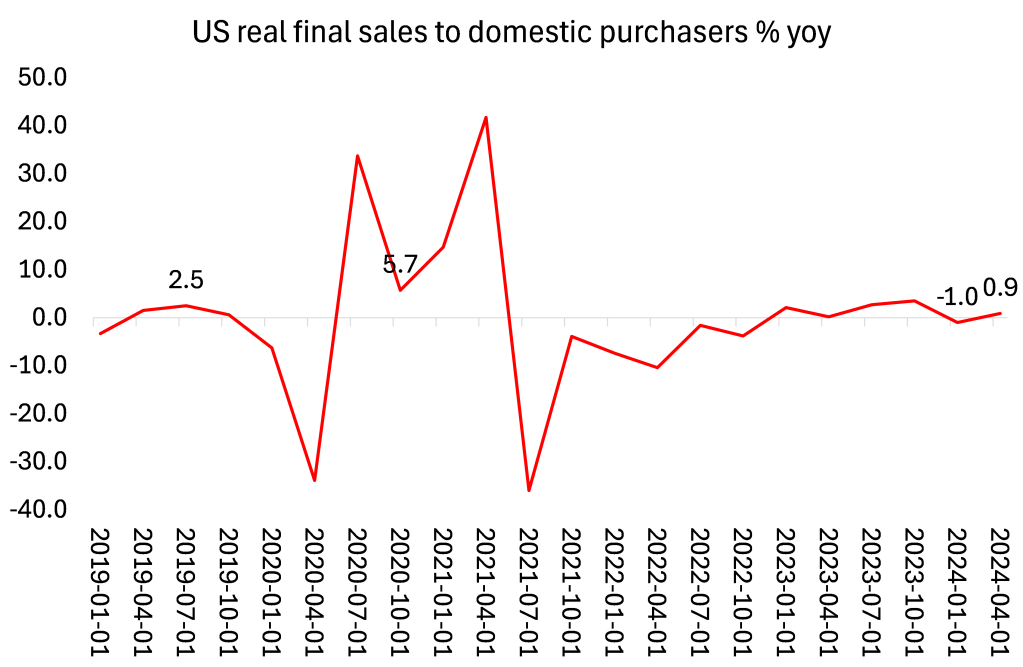

No increase in ‘real final sales’

If you strip all these components out and look at what is called ‘real final sales to private domestic purchasers’, a better measure of US economic activity, then there was no improvement over the weak first quarter. Indeed, growth in real final sales in the first half of this year has been zero compared to around 2% over the whole of 2023.

And sales to consumers have been better than real personal income growth. On average, American households, after two years of reductions in real incomes, are reaping only a very small rise now. Real personal disposable income (that’s income going to people after inflation and taxes are taken into account) rose at only a 1% annualised rate, slower than in the first quarter.

No wonder US consumer sentiment fell to its lowest level in eight months. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index registered a final reading of 66.4 in July, the lowest since November. The mainstream economists, believing that consumer spending and incomes are booming, have been puzzled by this, calling it a ‘vibecession’. American households don’t seem to realise that they are doing very well! But “high prices continue to drag down attitudes, particularly for those with lower incomes,” said Joanne Hsu, the Michigan survey’s director.

Bad news on the production front

That’s the consumer front. On the production front, it is not looking much better. The US corporate earnings season has commenced and there has been bad news across the board, particularly with the mega tech and social media companies that dominate the US stock market and take the bulk of profits in the corporate sector.

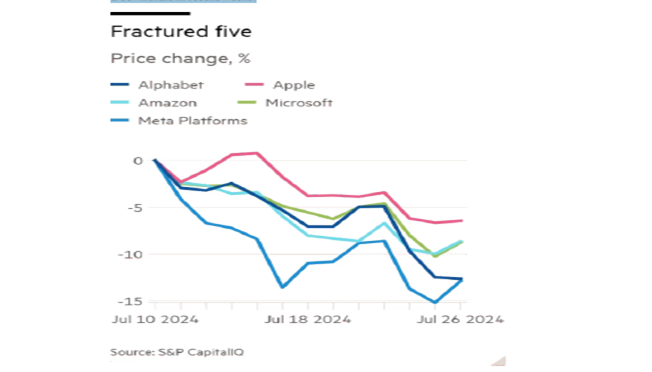

Four of the so-called Magnificent Seven technology stocks that have powered the US market rally for the past nine months ended the week in ‘correction territory’ for their stock prices, having fallen by more than 10 per cent from recent peaks. Another two — Microsoft and Amazon — are close to the double-digit falls that define a correction. From a Magnificent Seven to a Fractured Five!

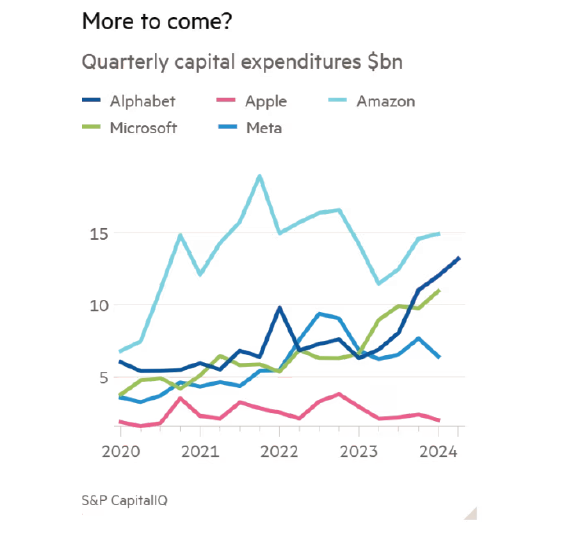

Doubts growing about future profits from AI

Big Tech has committed its fortunes to expected huge profits from AI. They have launched unprecedented levels of investment, and thus become the main driver of business investment in the US economy. Microsoft has said “we expect capital expenditures to increase materially” this year and that “near-term AI demand is a bit higher than our available capacity”. Amazon says strong demand for cloud services and AI means it will “meaningfully increase” capital expenditures. Meta says AI is driving higher investment both this year and into 2025. But doubts about the quick realisation of higher profits from AI are beginning to emerge and if Big Tech starts reducing its spending than that will reverberate through the corporate economy. There is more talk of ‘tail risk’ for the stock market.

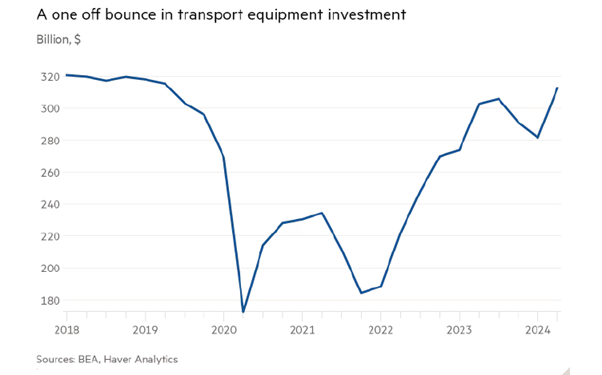

Also share prices in UPS, the delivery company often seen as a bellwether for the broader economy, dropped 12 per cent after UPS scaled back its forecasts for the rest of the year. Since the end of the pandemic there has been a huge rise in investment in transport equipment to handle the increase in global output. But that seems to be coming to an end.

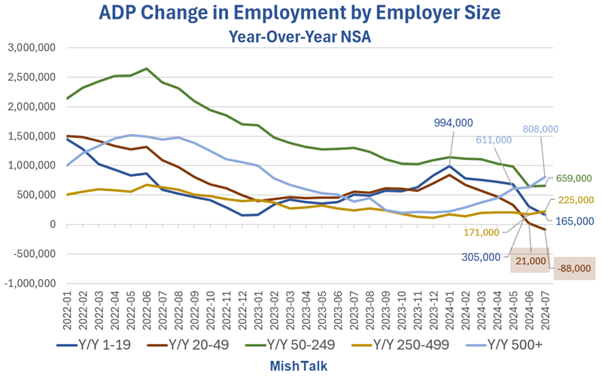

As for employment, again the overall picture is one of weakening employment growth and rising unemployment. ADP data shows year-over-year payroll growth is a negative 88,000 for small corporations employing 20-49 workers. And trends are negative in all but very large corporations.

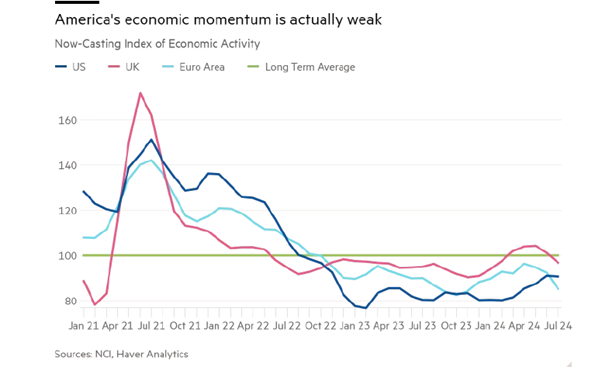

Indeed, the forward momentum in economic activity is weakening.

The reality is that the US economy may be the best performing in the top G7 economies, but it is not racing along. Even so, the situation in Europe and Japan is much worse – something I shall return to in a future post. The UK is so bad that the Bank of England has decided to cut its policy rate now. UK headline inflation has fallen sharply to 2%, but only because the UK economy is stagnating.

The choice facing the Federal Reserve

To sum up. The Federal Reserve will almost certainly start to cut its policy rate at its September meeting – and it has indicated just that. But that’s because it has no choice if it is avoid stagnation or even recession in the economy, like the UK’s Bank of England already faces. So the Fed will have to live with failing to achieve its 2% inflation target. And American households will face yet more inflation in the shops and in key services.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.