Andy Ford continues his occasional series of 80-year-anniversary articles on the Soviet Union in the Second World War. Part one of this article on the partisans can be read here. This article deals with the period 1943-4

[photo shows Soviet partisan railway attacks]

*********

As Hitler’s attempted conquest of the USSR became bogged down, the Soviet partisans gradually shifted from mere harassment of the occupiers to becoming a real factor in the military situation.

One of the first major military encounters between the partisans and German troops came in the prelude and aftermath of the Battle of Kursk in summer 1943.

Failure of German anti-partisan operations

Just before the battle, the German High Command decided enough was enough. They were having to deal with 1,000 railway demolitions a month and needed the rail infrastructure based on Bryansk for a successful northern pincer movement around Kursk. For once they had the troops to take on the partisans in their forest strongholds and so launched a series of anti-partisan operations, collectively known as the Battle of the Bryansk Forests. From May 1943 to the end of June the Germans launched five anti-partisan operations. The tactics were simple but labour intensive – based on the formation of cordons around an area of forest and then sweeping through, metre by metre.

The results were mainly disappointing for the Nazis. Often the partisans were tipped off by local informants and melted away, refusing to give battle to superior German units. Even if they were surrounded, they could use their knowledge of the terrain to slip through the cordon at night, leaving the Germans to hack through miles of empty forest and swamp.

Three of the sweeps did no more than capture and destroy the partisan dugouts, and only one, Operation Ziggeubarron was recorded as a ‘success’ with 1,500 killed (half of whom were probably unarmed civilians), 1,500 captured, and 200 forest camps destroyed in the area south of Bryansk. But it had taken 60,000 soldiers and over 100 tanks to achieve these results. One internal report advised placing a soldier at 10 metre intervals to be sure to cover all the ground – in a trackless Russian swamp.

Finally, Operation Tannhauser in late June ended without even making serious contact. But the German forces then entered the Battle of Kursk already worn down by forest encounters with the partisans.

One German soldier wrote home:

“We entered a gloomy wilderness in our tanks. There wasn’t a single person anywhere. Everywhere the forests and marshes are haunted by the ghosts of the avengers. They would attack us unexpectedly, as if rising from under the earth. They cut us up to disappear like devils into the nether regions. The avengers pursue us everywhere. You are never safe from them. Damnation. I never experienced anything like it anywhere in the war. I cannot fight the spectres of the forest.”

(Friedrich Buschele, letter home. He later died in action)

Battle of Kursk 1943: The rail war

While the Nazi troops were massing in the area ready for the attack, the partisan bands kept their distance, with Wehrmacht records showing only two attacks in early July. But once the Germans had lost the battle and needed to retreat, the partisans were ordered into action. For the first time, the partisans worked in close cooperation with the Red Army.

[Photo – Bundesarchiv, Wehmeyer 1944]

On July 22, 1943, there were 220 demolitions on the railway running north-south behind the German front, and on the same day, the highly successful attack on the Osipovichi railway junction, using a mine supplied by the Red Army to a railway worker, Fyodor Kytlovich, which he attached, at great risk, to a fuel train. The consequent fire ripped through the railway junction, destroying two ammunition trains, the fuel train, and a consignment of much-prized German Tiger tanks.

On August 2, 10,000 charges were laid on rail lines, of which 8,000 detonated. 266 locomotives were damaged or destroyed and 500,000 feet of replacement rail stock made unusable. . In September, over a hundred evacuation trains were stuck in the marshalling yards at Gomel for 3 days due to partisan sabotage.

The partisans began to move from the railways to attack convoys on the roads, and as they liberated towns and villages they were able to deal with collaborators, which further reduced cooperation in the remaining area of German occupation. Whole companies of Ostruppen were mutinying, and defecting to the partisans, one notable example being the Russian SS Brigade ‘Druzhina’, formed from Russian POWs. They shot their German officers, and came over to the partisans, together with their Russian NCOs, and fought bravely with them from 1943 onwards. The retreat threatened to turn to chaos, and the Germans were forced to switch troops from fighting the Red Army to guarding their rear from partisan attacks.

As the winter of 1943 closed down large scale military operations by both sides, hundreds of thousands of armed partisans stood ready to assist the next series of Red Army offensives set for 1944. [see video here]

A career of evil racism – Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski

The German rear areas were pleading for more troops, but there were none to be had. Instead, anti-partisan operations were centralised under the control of one man, SS Lieutenant-General Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski. As the last part of his name indicates, von dem Bach-Zelewski was actually Polish by origin, being born in the region of Poland which had been ruled by Prussia from 1815 to 1918. Maybe because of that fact, to cover his origins, he became a fanatical German nationalist, and changed his name by deed poll from ‘Zelewski’ to the aristocratic-sounding German ‘von dem Bach’. Trotsky wrote about this phenomenon in his masterpiece, ‘What Is National Socialism?’

“Worthy of attention is the fact that the leaders of National Socialism are not native Germans but interlopers from Austria, like Hitler himself; from the former Baltic provinces of the Czar’s empire, like Rosenberg; and from the colonial countries, like Hess, who is Hitler’s present alternate for the party leadership. A barbarous din of nationalisms on the frontiers of civilisation was necessary to instil into its leaders those ideas which found response in the hearts of the most barbarous classes in Germany”.

[Leon Trotsky ‘What Is National Socialism’– see here]

After WW1, Bach-Zelewski led paramilitary operations against Polish uprisings in Silesia in 1919-20, and was later active in anti-Semitic organisations. In the early days of the German invasion of the USSR, he had commanded units of the notorious Einsatzgruppen as they murdered, robbed and brutalised Jews across the occupied Soviet territories in the earliest stage of the ‘Final Solution’. Under his command, 35,000 civilians were shot in a couple of weeks in Riga, Latvia, as well as more across northern Russia and Ukraine [see video here].

As a result, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was admitted to a German hospital suffering from nightmares, hallucinations, and stomach problems, due to opium abuse. On recovery he was assigned to anti-partisan operations in Byelorussia and northern Russia. He only had one tactic – unrestrained brutality and terror. His units were known to slaughter civilians in order to inflate the ‘kill totals’ given to the German High Command, and all inhabitants of the Soviet liberated zones were treated as enemies not civilians. The partisan ranks swelled daily as young people fled starvation, deportation and brutality under the Germans.

Von dem Bach finished his ‘career’ by suppressing the Warsaw Uprising in August-October 1944, where 200,000 civilians were killed and 80% of the city destroyed. Despite all this he was not charged at Nuremburg, and West Germany refused to extradite him to either Poland or the USSR.

Partisans in the North in 1944

In the North of the front, the relief of the siege of Leningrad in early 1944 was greatly assisted by partisan actions. Until that point the guerillas had kept themselves out of harm’s way, concentrating on organising their forces, sheltering civilians and organising food supplies. But as the Red Army swept out of the besieged city, the partisans were ordered into action, destroying railway lines, and mining roads so effectively that many German reinforcements had to get to the frontline on foot, if they arrived there at all.

For example, in January 1944, the Germans were in danger of losing the city of Novgorod, which would turn their whole defensive line, and so a division of Jaeger (light infantry) troops were ordered to reinforce the city. The Army Group North war diary records:

18 Jan 44

(1800) Chief of transportation reports that 8th Jaeger Division is being transported in nine trains. Four leave today and will arrive Novgorod area tomorrow if track stays open. Remaining will arrive 24 hours later if everything goes smoothly.

(2400) Report of attack by strong partisan bands on railway north and south of station at Utorgozh. About 140 demolitions.

19 Jan 44

(1100 ) Arrival of 8th Jaeger Division cannot be predicted due to numerous demolitions.

(1245) Forces in Novgorod can only get out to the southwest. Unless 8th Jaeger Division is committed now, enemy tanks will be in Luga [54 miles west of Novgorod] tomorrow. G-3 says that 8th Jaeger Division is moving by truck but will arrive at earliest tomorrow.

(1347) Eighteenth Army reports to OKH that 8th Jaeger Division much delayed by railroad demolitions. Numerous demolitions on other rail lines.

(1800) CG, Army Group North reports that 8th Jaeger Division arriving in army group sector only in small increments due to extensive railroad demolitions.

20 Jan 44

(0040) Staff of 8th Jaeger Division arrives in Eighteenth Army Area.

(0945) 8th Jaeger Division has to detrain in Utorgozh due to railroad demolitions. Arrival still uncertain.

(19:25) Arriving units have to go on foot from Utorgozh (to frontline via Medved to Vashkovo. (Thirty eight miles over unimproved roads)

(Quoted in ‘The Soviet Partisan Movement 1941-1944, Department of the US Army, 1954)

Crucially needed reinforcements ended up slogging over 38 miles of tracks – just to reach the frontline. No wonder the Germans were driven back to the frontiers of Estonia and Latvia.

In the Central sector – Byelorussia in 1944

By January 1944, the partisans in Byelorussia controlled huge blocks of countryside, not just the forests, leaving the Germans only in firm control of the main cities, and those towns, villages, bridges, railways and roads they chose to garrison. And every now and then one of the garrisons would be snuffed out, leading to horrific punitive expeditions which quite often shot 20, 50 or 100 civilians in revenge for each Nazi soldier killed.

In Byelorussia all German supplies (or retreating troops) had to go over just one double track railway line, plus 5 single track lines, and only one reasonably modern road. The partisans stood ready to strike all along these essential communication links. Once Operation Bagration (the huge Soviet offensive of June 1944) was launched, the partisans emerged from the swamps and forests to harry and attack, and in many cases wipe out, retreating German formations. It must have been terrifying as the Germans knew they could expect little mercy after all the atrocities of their three-year occupation and counter-insurgency. In one case only 900 Germans reached safety out of 15,000 retreating.

Partisan failure in Ukraine

In Ukraine the pro-Soviet partisans made little headway, partly due to the terrain, but mainly because of the complete lack of support of the Ukrainian masses for the Stalinist regime, which had suppressed their language and culture, repeatedly purged their administration, and had artificially created a deadly famine in the botched collectivisation of agriculture in the early 1930s, a famine in which millions died while Ukraine exported grain.

As the Red Army advanced, the Soviets redeployed several seasoned partisan bands from the Pripyat marshes [in the north and in Belarus] into Ukrainian territory to attack railway communications, but when these units moved into more purely Ukrainian areas, their effectiveness fell dramatically as they faced not just the Germans, but also various Ukrainian nationalist guerrilla groups.

These groups fought the Red Army, sometimes the Germans, and occasionally even each other, but one thing they did agree on was driving ethnic Poles out of Ukraine. Within the actual war, a murderous ethnic conflict unfolded between the Ukrainian militias and the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa), with whole villages destroyed and families massacred or driven out of their homes.

The main Ukrainian nationalist group was the OUN-B (Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists) commanded by the notorious anti-Semite, Stepan Bandera. For an example of the OUN-B’s deranged anti-Semitism, one of their proclamations said,

“The Jews as well as the Poles and Muscovites will be isolated and removed from administration posts…Our leaders can only be Ukrainians, not foreigners, who are enemies. The assimilation of Jews is not possible.”

Their blueprint for a future Ukraine was stated to be,

“There are elements that must be neutralised when a new system is created in Ukraine. These elements are: Muscovites, seeking to possess the Ukrainian lands…Jews, both individually and as a group…and the Poles in the western Ukrainian lands who have not renounced their dream of a Greater Poland”.

Quoted in ‘The Reckoning’, Prit Buttar

These motivations suited the Nazi occupiers, who used the OUN-B to supply men for police and paramilitary units, but as soon as Bandera tried to insist on a role in the governance of Ukraine he was arrested and taken, first to Berlin, and then to a concentration camp.

The OUN-B set up an armed wing, the UPA (‘Ukrayinska Povstanska Armiya’ or Ukrainian Insurgent Army) in February 1943, which after some initial resistance to the German occupation gradually fell into tacit co-operation with them against the Red Army. Their main focus, though, was action against the Poles in Ukraine, culminating in July 1943 in massacres of ethnic Poles in the Volhynia region in which 160 villages were burned and 8,000 people killed.

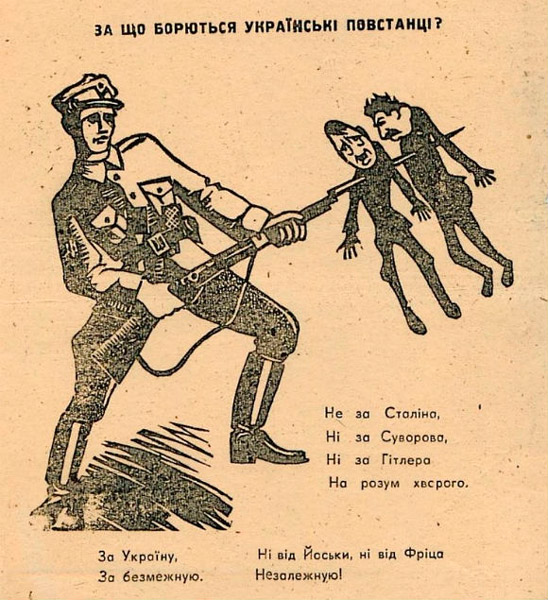

the Ukrainian Insurgent Army)

“no to Stalin, no to Hitler”

The UPA fought and harassed any Soviet partisans who strayed into ‘their’ domain, and as 1944 wore on, and the Red Army advanced, the UPA took up full scale war against them, even killing Soviet general Nikolai Vatutin. In revenge, the NKVD secret police were sent to Ukraine to snuff out the insurgency with their customary cruelty. In turn, the UPA set up a vicious counter-intelligence arm, the SB (‘Sluzhba Bezbeky’). The conflict with the UPA lasted well into the 1950s. For Ukraine, the horrific cumulative result of German occupation, Stalinist re-occupation, and UPA resistance followed by NKVD repression, was such that, of those boys born between 1924 and 1926, fewer than 3% survived the war.

Summary

The partisan movement of 1941 was less of a guerrilla army than a collection of bands of diverse origin whose only aim was to survive. Red Army remnants, civilian refugees from round-ups and forced labour, and the Jewish survivors of ghetto uprisings and massacres gradually came together in the Russian forests and swamps. In the words of a US Army study, “They seldom showed any aggressiveness; the paramount interest seems to have been one of immediate survival.”

But by 1942 they had progressed from mere survival to active self defence with occasional strikes against isolated stretches of railway. If the Germans did pursue they often faced ambush in the forests as the partisans knew every inch of the terrain. Liberated areas were established free from Nazi persecution.

As the military situation swung in favour of the Red Army in 1943 the partisans became a real factor in the military situation with thousands of railway derailments and attacks on retreating Nazi formations, and by 1944 they had become in effect a fourth arm of the Soviet armed forces, working in close contact with the high command and supplied with ammunition, artillery and medicines. But without mass support they could do nothing. In Ukraine and Crimea they were unable to make much contribution, and as the Red Army reached the old Soviet frontier, at the Baltic States, Poland and Romania, the partisan struggle faded away. In the words of Mao, “The guerrilla must move amongst the people like a fish in the sea.”

Trotsky had pointed out the impossibility of Hitler ruling Europe, even in the medium term, as it would require a soldier with a rifle behind each worker or peasant. But he was wrong about a revolutionary contagion spreading to Hitler’s armies. In one of his last writings he said:

“Hitler’s soldiers are German workers and peasants. After the betrayal of the social democracy and of the Comintern, these workers and peasants in large numbers succumbed to the fumes of chauvinism, thanks to the unprecedented military victories. But the reality of class relations is stronger than chauvinist intoxication. The armies of occupation must live side by side with the conquered peoples; they must observe the impoverishment and despair of the toiling masses; they must observe the latter’s attempts at resistance and protest, at first muffled and then more and more open and bold…The German soldiers, that is, the workers and peasants, will in the majority of cases have far more sympathy for the vanquished peoples than for their own ruling caste. The necessity to act at every step in the capacity of “pacifiers” and oppressors will swiftly disintegrate the armies of occupation, infecting them with a revolutionary spirit.”

(Trotsky, “The Fate of Hitler’s Armies”, August 1940)

That this never happened to any serious degree during the Nazi occupation of Russia was due in large measure to Stalin’s policy of patriotic war and incitement of blind hatred against all Germans, as Germans. The partisan oath included pure revenge and hatred:

“I swear to work a terrible, merciless, and unrelenting revenge upon the enemy for the burning of our cities and villages, for the murder of our children, and for the torture and atrocities committed against our people. BLOOD FOR BLOOD! DEATH FOR DEATH!”

The hate of the partisans for their enemy was quite natural considering what most of them had been through, but the Stalinists’ elevation of it to the main principle and motor force of the resistance prevented any internal dissolution of the German armies and in the long term cost far more lives. Trotsky was wrong, but only in so far as he had underestimated the degeneration of the Stalinist regime. He understood that war, and especially partisan war, is political. One of Lenin’s favourite sayings was “War is the continuation of politics by other means”. Stalin could not, in all seriousness, ask the partisans to fight for his regime, so they could only be motivated to fight against the occupiers.