Book review by John Pickard

Left Horizons has published a series of articles on the role of the Red Army in defeating Nazi Germany, often focusing on the eightieth anniversary of major turning points in the Second World War. This book by Svetlana Alexievich, The Unwomanly Face of War, provides an excellent complement to those articles, by looking at the human experience exclusively from the viewpoint of Russian women combatants.

The book is composed of a series of interviews recorded by Alexievich, between 1978 and 2004, and it provides a huge compendium of personal stories and reminiscences, many of them inspiring, many poignant, a few funny, but all of them interesting.

When men talk, or write, about war, Alexievich argues, it is about troop deployments, materiel, armaments, and battle formations and outcomes. “Women’s stories are different”; she says. They are about the human, psychological and emotional costs. “You should talk to my husband”, one very shy woman even told her, “…the names of commanders, the generals, the numbers of units – he remembers everything. I don’t. I only remember what happened to me…”

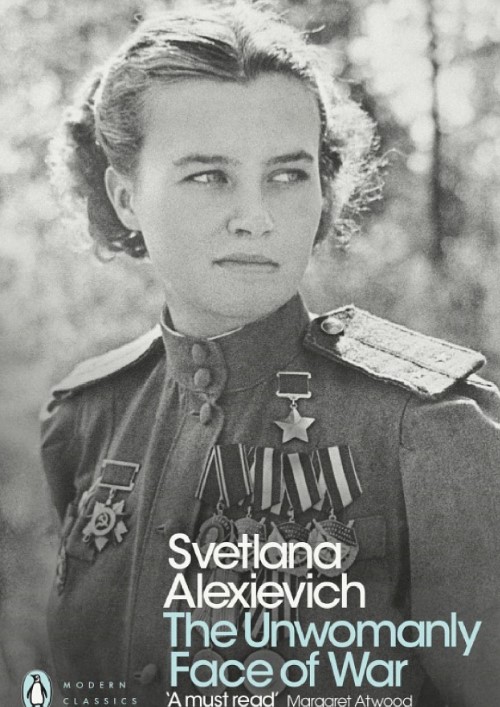

Alexievich was born in Ukraine, of a Belarussian father and a Ukrainian mother, but she was brought up in Belarus. When she won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2015, she was the first Belarussian writer to win that award. This book was her first, published in 1985 – it was to sell over two million copies in Russia alone – although the English translation was only published six years ago.

Many women enlisting were very young

About a million women fought in the Red Army and if these testimonies are anything to go by, they were overwhelmingly, volunteers, many of them very young, teenagers, one of them not even sixteen, and not infrequently having to demand at the recruiting office that they be allowed to enlist. Some even ran away from home to join the Red Army.

Like the men, they suffered the hardships and privations, the lice, the dirt, the mud and the injuries. One young women described how she “grew up” during the war – literally. When she finally got home, her mother measured her, and found she’d grown four inches.

The experiences of these woman varied enormously, not only in terms of their roles – there were snipers, pilots, engineers, mine-disposal specialists, anti-aircraft personnel, machine-gunners, radio-operators, medical staff and partisans – but as regards their experiences as women.

Some must have been in such a constant state of physical and emotional stress that their menstrual cycle went ‘on hold’ for the whole duration of the war. But for some others, it was normal, but in an army built around the needs of men, there were no sanitary provisions for mentstruating women, so they had to improvise with torn-up shirts and whatever came to hand. Many women were obllged, at least in the early stages of the war, to make do with the smallest possible sizes in the men’s uniforms, sometimes including boots several sizes too small.

Most of these women experienced the most intense conflicts, including hand-to-hand combat, bombardments, partisan warfare and major battles. Many of them were decorated for their courage. One medical orderly described dragging injured soldiers back to the lines and away from exposure to machine-gun and mortar fire. “Altogether, I carried 481 wounded soldiers from under fire. It’s hard to believe now…I myself found it hard to believe.”

Without the 1937 purges, there would have been no 1941 retreat

Some of the women went through the entire war shutting ‘romance’ out of their lives – they were surrounded by men, but saw themselves primarily as soldiers and didn’t even want to wear dresses or ‘women’s clothing’. But some others did want to hang onto what they saw as their feminity. Some even found husbands in their units, partners who sometimes did and sometimes didn’t survive the war to go home with them.

Although the big majority of women’s testimonies did not offer any description of the political atmosphere in Stalinist Russia, a few of them did. Long before the Nazi invasion, in 1941, Stalin had completely decapitated the Red Army.

In the purges of 1937, tens of thousands of the best Red Army officers, including many who had distinguished themselves in the Civil War twenty years earlier, were either shot or sent to the camps. Mikhail Tukhachevsky, for example, a distinguished general, was shot. Stalin so weakened the Red Army that in 1941, the Nazis found the Russians were a push-over.

Alexievich, described, how with one of her interviewees, “We talked about Stalin, how before the war he had destroyed the best commanders, the military elite. About the brutal collectivization and about 1937. The camps and exiles. That without 1937, there would have been no 1941.”

“Let’s remember the catastophe of the first months of the war”, one woman told Alexievich, “our air force was destroyed on the ground, our tanks burned like matchboxes. The rifles were old. Millions of soldiers and officers were captured. Several million! In six weeks, Hitler was already near Moscow…University professors signed up to serve in the militia. Old professors! And girls were eager to get to the front voluntarily.”

Most of World War II was fought on the Eastern Front

The baleful effects of Stalin’s personal paranoia were effective as much after the war as before, with many Red Army personnel returning, not to a hero’s welcome, but to further repression – for committing the ‘crime’ of getting captured, or wounded, or for having had to retreat. “My husband”, one woman wrote to Alexievich, “a chevalier of the Order of Glory, got ten years in the labour camps after the war…that is how the Motherland met her heroes…”

The husband of one woman, also a soldier, was taken after the war by the NKVD [secret police], who broke one of his ribs, injured his kidney. “he was captured by the fascists, they smashed his skull, broke his arm. He turned grey there, and in 1945, the NKVD made him an invalid for good…”

The book leaves a vivid impression of the privations of the population and particularly the Red Army personnel during the war. The women who had served with the partisans gave particularly gruesome descriptions of the massacres the Nazis visited on Russian villages they captured. Few Russians prisoners of war ever made it back home, so brutally were they treated.

The Soviet Union lost somewhere between twenty and twenty-four million dead in World War Two, far more than any other nation, and after the war, there were many villages that were re-established composed entirely of women.

Some of the most revealing comments were those made by women who had gone with the Red Army all the way into Germany and got some measure of the German living standards, compared to those in Stalinist Russia. “The first thing that struck us”, one of them said, “was the good roads. The big farmhouses…flowerpots, pretty curtains in the windows, even in the barns. White tablecloths in the houses. Expensive tableware. Porcelain. There I saw a washing machine for the first time…we couldn’t understand why they had to fight if they lived so well. Our people huddled in dugouts, while they had white tablecloths. Coffee in small cups…”

Hollywood and the British film industry would like us to believe that D-day and the Western front was vitally important in the destruction of the Nazis, but that is far from the truth. The Second World War was fought largely on the Eastern Front, which saw more deaths than all other theatres of the war combined. Germany itself, lost 80% of its war dead on the Eastern Front.

Medals they did not want to wear in public

As becomes clear in the book, different women had different experiences, both during and after the war. Some of them related how they were often shunned afterwards. Despite giving their all, they were often treated with disdain afterwards – as if soldiering was not a fitting occupation for a woman. Sometimes their morality was even questioned for having been part of an army full of men, as if that had been their motivation.

Most of the women returnees received medals for heroic service, but some were reluctant to wear them in public, at least for some years afterwards. It was clear, however, that by the time they were being interviewed for this book, many of the women were involved in associations and reunions of woman veterans and they were more than happy to share their experiences.

Alexievich says in her introduction, that in the Soviet Union, “the War was remembered all the time.”. It would have been in the 1950s and 1960s when she was at school, but she noted that “in the school library, half of the books were about the war.”

How much of that ‘Victory’ tradition is exploited today by Putin.

By the time she was recording her interviews, the women who fought were old, most of them grandmothers, and by today, they will have all passed away. But memories live on. These women will have told their stories and related their experiences to their children and grandchildren, and the traditions of the old are passed on – at least partly – to become the traditions of the young.

The reason why that is important is that the overwhelming majority of these women were volunteers in the war effort: they saw it as their moral duty to defend ‘Mother Russia’. That patriotism and the knowledge of a bitterly-fought and hard won ‘Victory’ was still with them in old age, decades after the war.

Reading this book today, in 2024, it does raise a question – about how much Vladimir Putin is cynically using those feelings and the tradition of the heroic defence of Russia from Nazi attack in 1941, to ‘justify’ – at least among a part of the population – launching the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It is certainly food for thought. For all of those readers who have enjoyed Andy Ford’s Left Horizons articles on the fortunes of the Red Army, this book is a must.

Svetlana Alexievich in 2016, from Wikimedia Commons, here.