Throughout this 40th anniversary year of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular bulletins on important issues and developments that occurred during the strike, month by month, as well as specific articles analysing major events.

This update covers the period between 20 July and 17 August 1984.

*******

The 20 July saw the serious disappointment of the deal between the government and the dockers, leaving the miners to fight on alone. This period also saw the court’s fine of South Wales NUM and the subsequent seizure of its funds, further police harassment and violence and the famous characterisation of the mining communities by Thatcher as “The Enemy Within” – contrasted with the recovery of the Falkland Islands from the Argentinian military junta, the enemy “without”.

The resilience and determination of the miners and the women of the mining communities, still fighting after almost six long months of bitter struggle, shocked and surprised the Tory government and the ruling class. It also inspired millions of working-class people, who looked forward to victory as the summer turned to autumn and winter and the need for coal increased. 120,000 miners were still on strike, with only a few hundred going back to work.

The dock strike had been absolutely solid, more so than in previous disputes, as even dockers in ports not registered under the National Dock Labour Scheme had come out in support. Yet, in the early hours of 20 July, a deal was struck in which the employers merely agreed to request local employers not to break the dock labour scheme. On these shaky grounds, the chance of a united fightback against the Tory government was sacrificed by the leaders of the transport workers union (TGWU) and the dock strike was called off, much to the relief of Thatcher and her gang.

Thatcher was risking serious damage to the economy by pursuing the vendetta against the miners. And that was after Tory policies. and the slump of the early 80s, had destroyed one fifth of British industry, leading to investment falling by one third as well as levels of mass unemployment that had not been seen since the Second World War. Only the free-flowing revenues from North Sea Oil were coming to Thatcher’s rescue. She was playing for high stakes and could not afford to lose – hence her desperation and ruthlessness.

Fear of provoking the miners

The Times referred to the strike as a war. [Militant 27 July]. They later called for a “punitive settlement”. The Financial Times carried an article from Thatcher’s ally Samuel Brittan calling for pits to be closed immediately and urging “no appeasement”. Yet an editorial in the same Financial Times, the more sober voice of the capitalist class, warned against such inflammatory language which underestimated the feelings of genuine resentment about pit closures among the population and a “residue of public sympathy for the miners and their way of life”. It feared provoking the miners into unifying behind their leaders. [Militant 27 July].

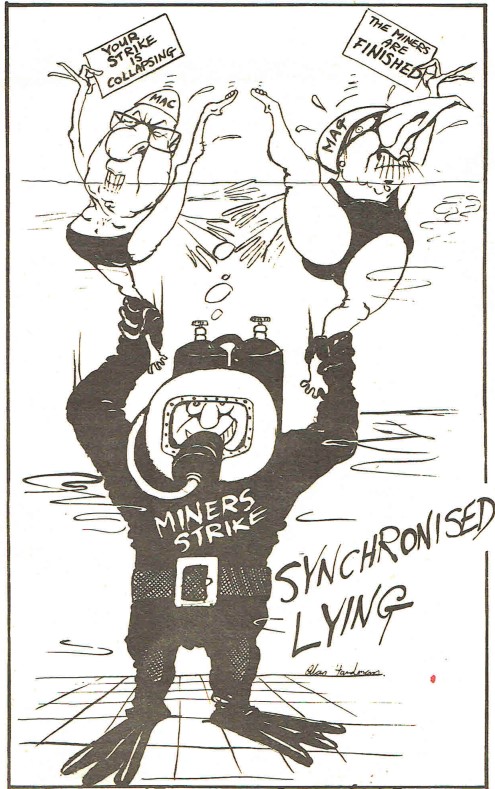

Ian McGregor of the Coal Board and Thatcher

The more far-sighted representatives of capitalism realised that there was much more widespread support for the miners among layers of middle class and professional people, many of whom were trade unionists themselves, than in 1926 during the General Strike or the long miners’ strike that followed it. Back then, these sections of society actively scabbed. The feelings were that if the strike carried on into the autumn or even the winter, that the Emergency Powers Acts of 1920 and 1964 may be used to mobilise troops to move coal but that would risk a fierce backlash from the organised labour movement, which was still a powerful force in society.

By this stage of the dispute, the striking miners and the women of the mining communities had become profoundly radicalised. Every strike, even short disputes, have effect of posing the question of where power lies – with the bosses or the workers. As strikes continue, this leads to a wider questioning of that relationship and of the structure of society as a whole and a more generalised support for socialist ideas.

After such a long and bitter dispute as the miners’ strike, these radical ideas were spreading way beyond the mining communities. The whole country was becoming sharply polarised between those who supported the miners and those who did not. Many felt that after the strike had lasted so long, a defeat was inconceivable.

Then, on 1 August 1984, a judge imposed a fine of £50,000 on the South Wales NUM. This was in relation to a case brought by two millionaires, George and Richard Read who were owners of a lorry company that was scabbing by transporting coal. They won an injunction against South Wales NUM, barring them from “interfering” with the lorries. The union stood firm, and refused to pay and had now been fined.

No surrender to Tory anti-union laws!

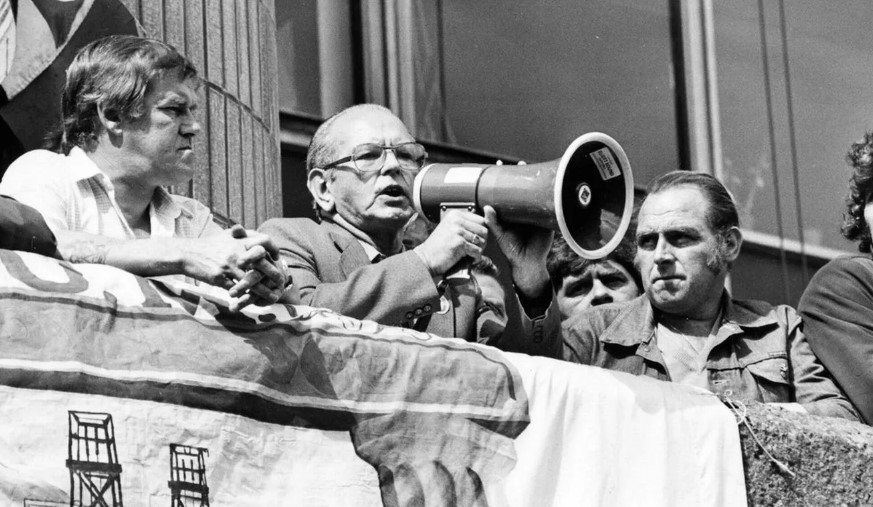

The day of the judgement the union offices in Pontypridd were taken over by hundreds of miners who packed into the rooms, corridors and staircases. The sign on the door proclaimed “No Surrender!” 5,000 people attended a demonstration outside, including 300 young socialists from a summer camp that was being held in the nearby Forest of Dean. They heard Emlyn Williams, the President of the South Wales Miners, call for any attempt at sequestration to be met by a campaign of mass resistance by the labour movement. He called on trade union leaders to “put their muscle where their mouth is” and warned that there should be not repeat of the betrayal of 1926.

President of the South Wales NUM – speaking from the balcony of union HQ – 1 August1984

The order was made to sequester (i.e. seize) the union’s assets and a firm of auditors were impounding any funds that could be traced back to the union, including money that had been donated to ease the hardship of miners’ children.

Emlyn Williams, in an interview with Militant published on 10 August, was clear.

“We will not enter any court where a case is placed against us under the 1982 Employment Act. We will have nothing to do with any anti-trade union legislation. There is no way we will ever back down…We will resist it by whatever means we have at our disposal.”

He had little faith in waiting for the election of a Labour government, and instead he insisted

“The only answer is with the working people of this country. To them we make our appeal. We live or die by their response.”

When asked to comment on the mood of the miners, he replied

“Well there is not a crack in the armour of the miners. This sequestration has only hardened them; you can go around any of our mining villages and talk to whoever you like. Yes, we’ve got one or two dissidents but taking the mass of miners, their families, their children, they are as dedicated now as they were on day one…I believe that the miners look upon themselves now not only as the vanguard but as people who are going to help change society.

“I’ve noticed particularly when our young lads do an interview, how articulate they are and how knowledgeable. Many were saying that these youngsters wouldn’t fight because they had got cars and many had a rich way of life. That bubble burst in the first month. Their cars, their videos, their TVs have gone, they have a new way of life now, a makeshift way of life. Bills don’t worry them anymore. They are dedicated. They have been taught that the important thing is to read, read and read and understand what society is all about.

“They know the political score and they know the kind of society they want to see. It’s the ideals and aspirations of the old socialists that are coming out in the youngsters. I am very proud of them. They will never be the same.”

[Militant 10 August 1984]

Emlyn Williams supported the idea of the NUM calling for a one-day general strike themselves, if they had to, but he called on the TUC and the Labour Party to take the lead in organising it.

As for the Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, of course, he opposed any solidarity strikes and said that the fine should be paid. He opposed the call for a one-day general strike, sneeringly describing such action as suited to the US or Europe but not Britain.

Public support for the strike, however was increasing daily, as money from street and workplace collections poured in. Trade unions in Ireland funded a holiday in Waterford for 25 miners’ children, with the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) donating £5,500. Meanwhile, the Polish independent union Solidarnosc had written to their government protesting about the sending of scab coal to Britain by the self-styled “socialist” government.

Women – backbone of the strike

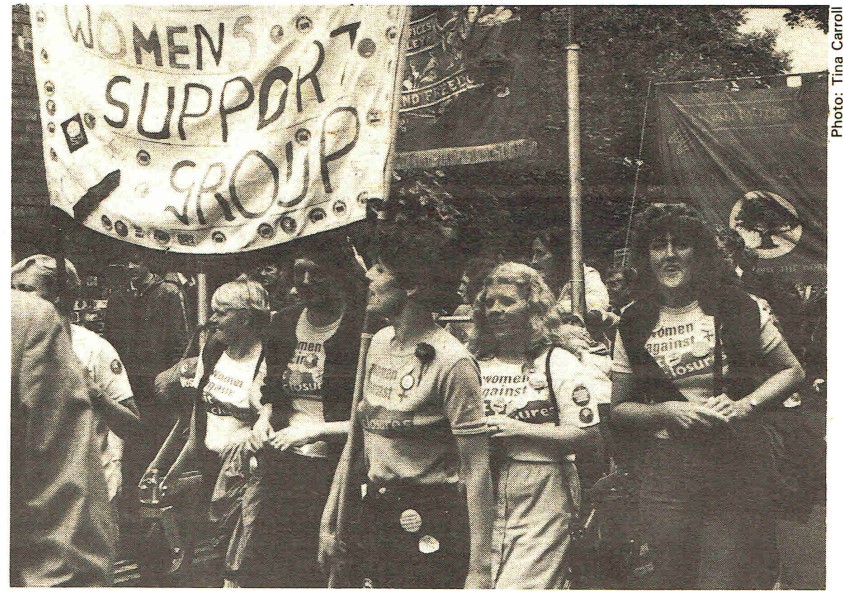

The crucial factor in the success of the strike so far was the resolute support of the miners’ wives and women in the mining communities. Thatcher assumed that the strike would crumble under pressure from miners’ families, but the opposite occurred as women organised themselves to form a strong backbone to the dispute. The Times described the role of the women as the “turning point” in the strike. On 11 August, the organisation Women Against Pit Closures organised a national demonstration in London attended by 20,000.

Militant 17 August [photo – Tina Carroll]

The women’s organisations were providing the thousands of meals a day, raising money and providing hundreds of food-parcels a week, a central task in keeping the strike going [Militant 10 August]. But they were also picketing and learning first-hand about the nature of the police. In South Wales, for example, women were picketing Port Talbot steelworks, and speaking at rallies all over the country, including in those areas where striking miners were a minority, such as Nottinghamshire. As one woman who was involved in a huge rally in Barnsley said:

“We’ve never done anything like this before. You don’t have time to study how you feel about it. You just have to do it.”

Another said:

“We’ve also been picketing. We enjoy it – it’s done like a military strategy. We’ve no fear of the police in spite of their treatment.”

Women such as these were becoming admired and respected throughout the country as a key part of the labour movement in their own right.

In Monkwearmouth colliery in Sunderland, two women were actually NUM members. They worked in the colliery canteen and after initial hesitation had thrown themselves into the local support group. Julie Ross said

“18 weeks is not long time in anyone’s life but the strike has opened the door to a new world and it will never be closed again.”

Back to work movements?

In South Wales a woman named Joy Watson was getting media backing for trying to start a “back-to-work” movement. Women who supported the strike organised a 500-strong demo in her home town, and she eventually agreed to meet. She claimed that men were only on strike because of mass picketing, yet in South Wales there was often just a token picket or none at all. The meeting came to nothing and her “movement” had no effect whatever in encouraging men back to work [Militant 17 August]

Another, shadowy, figure who went by the name of “Silver Birch” was also trying to organise a return to work. Though beloved by the press, he spoiled his image rather when he admitted to the Daily Mail [25 July] that he was funded by rich donors who wanted the strike to end! When he organised a well-funded campaign, backed by the media, to target Bilston Glen pit in Midlothian, Scotland, the result was only 36 miners returning to work out of 1,800.

That was still 36 too many, of course, so the strikers withdrew permission for safety cover. Management started to allow inadequately trained staff to do the safety work, which worried the usual pit deputies in the NACODS union. The need for the NUM and NACODS to work together was clear.

There had been four recent arrests of miners at Bilston Glen; one had been fined £500 and he and another miner were sacked for being arrested on a picket line. During a picket at the nearby Gorebridge privately-owned mine, six miners were held on charges of “riot” – the first time that had been used in Scotland – as a method of intimidation.

In Bold, in Lancashire, 15 pickets were arrested for “suspicion of criminal damage” and were held in just one cell for 10 hours in appalling conditions [Militant 27 July].

Police “go wild” in astonishing attack

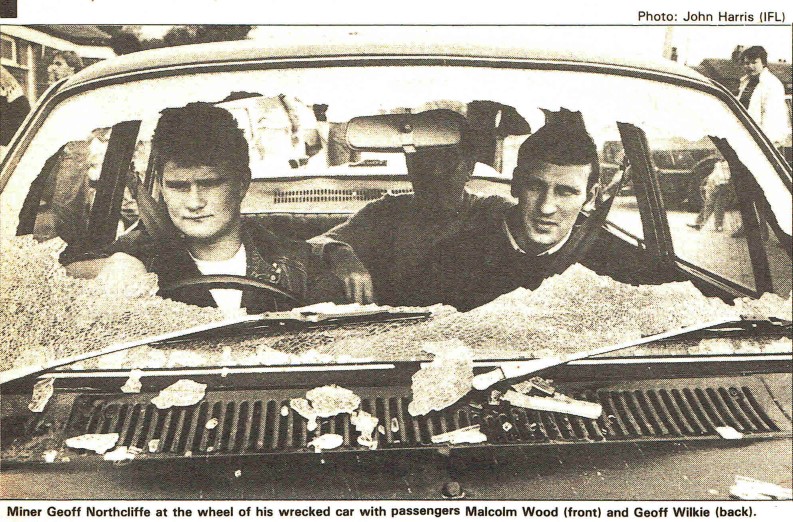

On 13 August, near the Yorkshire/Nottinghamshire border, there was an astonishing attack on miners by the police. A convoy of about 30 cars carrying miners intending to go to Warsop colliery was blocked from entering Nottinghamshire by police at 3.30 am. While the miners were parked up, deciding what to do next, five van-loads of police arrived and stood 4 or 5 deep, blocking any exits, and banging their shields “like Zulus”. They then attacked the cars with their truncheons, smashing the windows, denting the metalwork and dragging out and handcuffing some drivers. Geoff Northcliffe told Militant [17 August]:

“I sat in the car, covered with glass, waiting for my turn. I was scared death…I have never seen anything like this. We’ve been stopped at road blocks many times, but there’s been nothing like this. The police just went wild.”

There were still important victories. Movement of coal by rail in the London-Midland area (which covers Nottinghamshire) fell by 90 percent between July and August, from 100,000 tonnes a week to just 10,000. Elsewhere, solidarity by rail workers had ensured that coal was not being moved. The normal movement of coal before the strike had been 2 million tonnes per week!

Other workers were pursuing their own disputes. Workers occupied British Aerospace in Bristol. Domestic workers at Barking Hospital, in NUPE and NALGO (now merged in UNISON), had been on strike as long as the miners. Post Office engineers announced an overtime ban. A postal workers’ strike in the North-West of England won in a victimisation dispute [Militant 17 August].

Most importantly, the rail unions, were involved in their own action. The NUR organised a day of action with some strike action together with a national demonstration in Derby on behalf of the engine workshops threatened with job cuts. London Transport workers had planned for a one-day strike on 12 September and there were calls to make this national one-day strike.

As this mood of militancy was building, all attention was turned to the TUC conference. A lobby of the conference was planned for 3 September, calling for support for the miners and for the TUC to resist the Tory anti-union laws, with many calling on the TUC to call a one-day general strike. If the TUC acted in full solidarity with the NUM, victory was felt to be assured.

[Much of the information in this article comes from the socialist newspaper, Militant, issues 27 July – 17 August 1984]