By Michael Roberts

Every August the world’s top central bankers meet in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, a ski resort in central US for a ‘symposium’ organized by the Kansas City Federal Reserve. The bankers take this opportunity to discuss monetary policy and its efficacy in ‘managing the economy’, in particular, ‘controlling’ inflation and providing the right amount of ‘liquidity’ to the financial system.

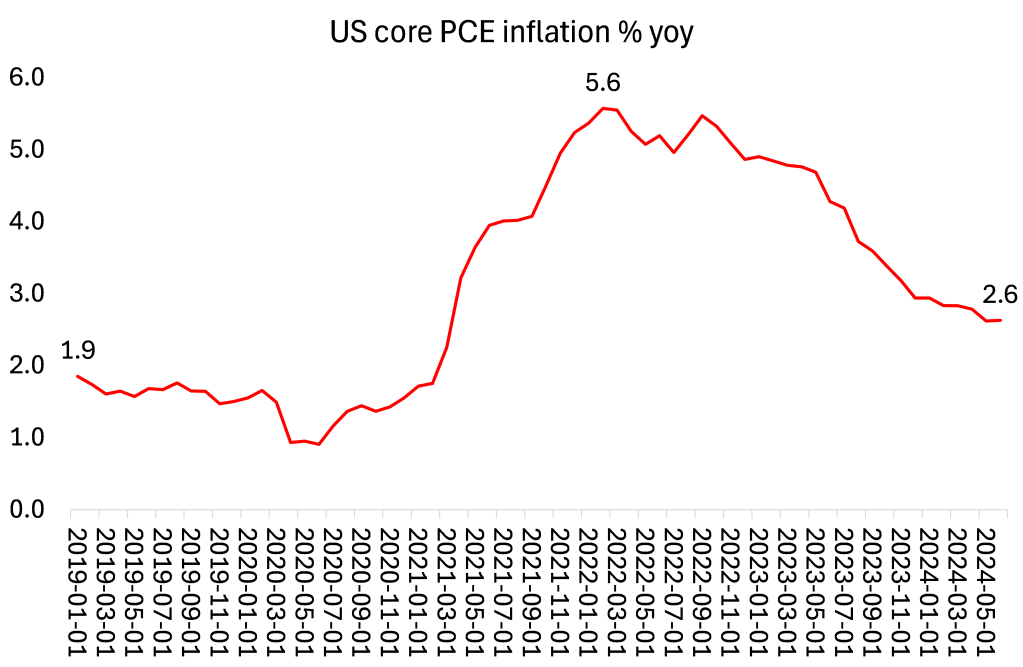

This year’s symposium took place when the US Federal Reserve has been put on the spot about whether it should cut its ‘policy’ interest rate, given some signs of a cooling economy and yet a ‘stickiness’ in the fall in the inflation rate towards the Fed target of 2% a year. The so-called policy rate sets the floor for all interest rates on borrowing for households and businesses in the US (and for most of the world). And currently it is at its highest in 23 years.

The Fed’s decision making over the policy rate

In early August, the financial markets panicked and started selling corporate stocks because the Fed decided not to cut the policy rate at its July meeting and then the jobs figures for July showed a sharp fall in net job increases with unemployment rising. However, then the latest inflation data came in showing a further (mild) fall in the inflation rate and markets calmed down, especially as Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell started to give clear signals that the central bank will cut its interest rate at its September meeting.

Powell repeated that view during his Friday speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium. “Progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. My confidence has grown that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent….. The labor market has cooled considerably from its formerly overheated state. It seems unlikely that the labor market will be a source of elevated inflationary pressures anytime soon….. We do not seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions. The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.”

Powell then went on to claim that inflation had come down without a recession in the US economy because of the Fed’s monetary policy. “Our restrictive monetary policy helped restore balance between aggregate supply and demand, easing inflationary pressures and ensuring that inflation expectations remained well anchored.” He argued that the inflation of prices had rocketed because of a combination of rising consumer spending and supply shortages. This is true, but the issue is which was the most dominant factor. Most, if not all, research on the inflation period has shown that it was supply factors that dominated, not excessive demand from consumers, government spending or ‘excessive’ wage increases – the arguments presented at the time by central bankers to justify the huge hikes in interest rates.

The real reasons inflation has reduced

But in his speech Powell hinted at the real causes when he said: “high rates of inflation were a global phenomenon, reflecting common experiences: rapid increases in the demand for goods, strained supply chains, tight labor markets, and sharp hikes in commodity prices.” And that explained the fall in the inflation rate later: “Pandemic-related distortions to supply and demand, as well as severe shocks to energy and commodity markets, were important drivers of high inflation, and their reversal has been a key part of the story of its decline. The unwinding of these factors took much longer than expected but ultimately played a large role in the subsequent disinflation.”

Nevertheless, Powell continued to push the narrative that it was the central banks’ “restrictive monetary policy” that did the trick by “moderating aggregate demand”. Powell also reiterated the myth that central bank monetary policy helps to “anchor inflation expectations” which, it is claimed is key to controlling inflation. But again this is nonsense, as recent studies have clearly shown that ‘expectations’ have little or no effect on inflation. As Federal Reserve economist Rudd recently concluded: “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case can be made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

Powell also dished up the other mainstream concepts to explain inflation and so justify their ‘restrictive monetary policy’. First was the so-called ‘natural rate of unemployment’ (NAIRU). The theory is that there is some rate of unemployment that is low enough to sustain economic growth without inflation but not too high to indicate a slump. But NAIRU is another ephemeral and movable feast that cannot be measured.

NAIRU is related to the so-called Phillips curve, a Keynesian concoction that argues inflation is caused by excessive wage rises when the labour market is too ‘tight’ (ie the unemployment rate is below NAIRU). There is a ‘trade-off’ between wages and inflation. This theory was empirically refuted back in the 1970s when economies experienced ‘stagflation’ ie rising unemployment, low growth and rising inflation.

The false idea of a ‘natural rate of interest’

And since then, there have been several studies to show that there is no ‘curve’ at all, no correlation between movements in unemployment, wages and inflation. Indeed, Powell’s’ comments on NAIRU were in direct contradiction to what he said at the 2018 Jackson Hole symposium. Then Powell suggested that following the usual conventional ‘stars’, namely NAIRU, to gauge when the economy is at optimum speed), or the natural rate of interest (to gauge when the cost of borrowing is about right) may not be of any use.

Again, the idea that there is a natural rate of interest which keeps inflation down without damaging economic expansion and central banks should measure this and keep to it does not hold with the reality of capitalist production. Even hardline ECB central banker Isabel Schnabel has admitted that: “The problem is it cannot be estimated with any confidence, which means that it is extremely hard to operationalize …. The problem is we don’t know where it is precisely.”(!)

Apparently, these natural rates for harmonious non-inflationary growth keep moving about! “Navigating by the stars can sound straightforward. Guiding policy by the stars in practice, however, has been quite challenging of late because our best assessments of the location of the stars have been changing significantly. Schnabel went on: “Experience has revealed two realities about the relation between inflation and unemployment, and these bear directly on the two questions I started with. First, the stars are sometimes far from where we perceive them to be. In particular, we now know that the level of the unemployment rate relative to our real-time estimate of NAIRU (u*) will sometimes be a misleading indicator of the state of the economy or of future inflation. Second, the reverse also seems to be true: Inflation may no longer be the first or best indicator of a tight labor market and rising pressures on resource utilization.” So useless then as indicators.

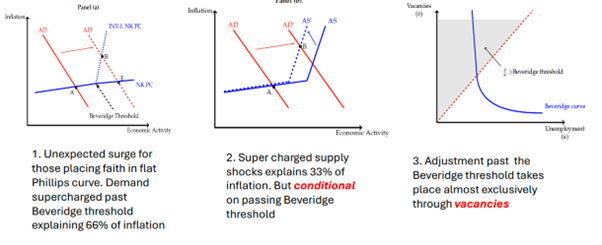

Inflation theories – the Phillips curve and Beveridge threshold

The 2024 Jackson Hole symposium continued with the presentation of papers on the efficacy of monetary policy by several highly esteemed mainstream economists. One such paper reexamined the Phillips and Beveridge curves as explanations of the inflation surge in the U.S. post the pandemic slump of 2020. The Beveridge curve describes where, as job vacancies rise, inflation rises and vice versa. The presenters told the central bankers that “that the pre-surge consensus regarding both curves requires substantial revision.” In other words, the recent post-COVID inflation spike could not be explained by existing mainstream theories. The presenters tried to come up with a revised series of curves based now on job vacancies not unemployment.

Nevertheless Powell claimed success for monetary policy: “all told, the healing from pandemic distortions, our efforts to moderate aggregate demand, and the anchoring of expectations have worked together to put inflation on what increasingly appears to be a sustainable path to our 2 percent objective.” And this was without a recession that was once feared and panicked financial markets only three weeks ago. The ‘soft landing’ for the economy is still on the cards and the ‘Goldilocks’ scenario of robust economic growth and low unemployment along with low inflation is nearly with us.

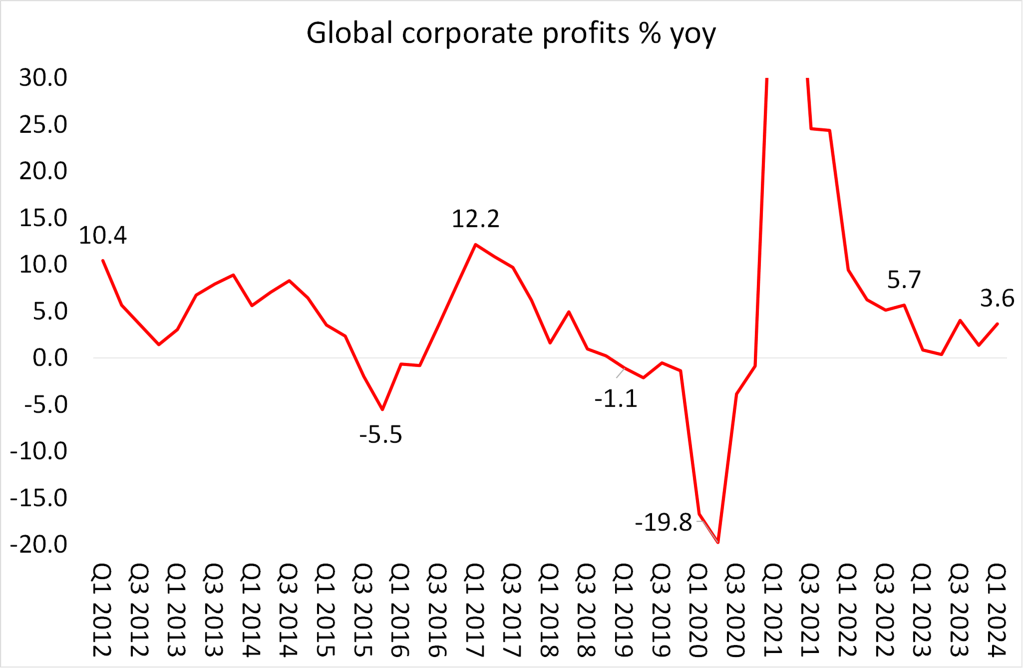

Corporate profits – the key indicator of recessions

Now I have argued in previous posts that the market meltdown three weeks ago does not yet herald a recession. For me, the key indicator for that is first: corporate profits. And so far, they have not descended into negative territory in the major economies.

But the US economy and the other major economies are by no means out of the woods. Price inflation remains ‘sticky’ ie looking as though it will stick around at least 1% pt above central bank targets.

And this is something that worries the central bankers from Europe attending the symposium. Bank of England governor Bailey put it this way: “We still face the question of whether this persistent element is on course to decline to a level consistent with inflation being at target on a sustained basis and what it will take to make that happen. Is the decline of persistence now almost baked in as the shocks to headline inflation unwind, or will it also require a negative output gap to open up, or are we experiencing a more permanent change to price, wage and margin setting which would require monetary policy to remain tighter for longer?” And the ECB chief economist Philip Lane was equally sceptical that monetary policy could go the ‘last mile’ in the ‘war against inflation’.

Real GDP growth is very weak

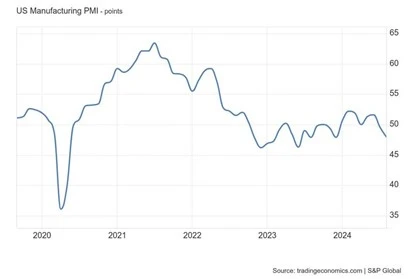

At the same time, in the major economies, real GDP growth (and especially real output per capita growth) is very weak. Only the US has any significant expansion and even there, when you strip out exports and stockpiles, sales growth is no more than 1%. The rest of the G7 economies remain either in stagnation (France, Italy, UK) or in recession (Japan, Germany, Canada). It is no better in other advanced capitalist economies (Australia, Netherlands, Sweden, New Zealand). And the manufacturing sectors of nearly all the major economies are deeply in contraction territory.

Moreover, soon there will be a new US President that either wants to hike import tariffs to record levels, so strangling world trade and pushing up imports prices; or alternatively she wants to impose new taxes on corporate profits – neither is good news for US capital.

The symposium revealed the limitations of central bank monetary policy

The Jackson Hole symposium celebrated success but what it really revealed is that central bank monetary policy played little role in getting inflation down from its peaks in 2022; that it has played little role in achieving output or investment growth; and it has little power to stop unemployment rising or any slump in production ahead. All high interest rates have done is to drive many small businesses into bankruptcy or more debt; and drive mortgage rates and rents to peaks in housing. And cutting interest rates now will merely fuel the stock market, not the economy.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.