Throughout this 40th anniversary year of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular bulletins on important issues and developments that occurred during the strike, month by month, as well as specific articles analysing major events.

This update covers the period between 17 August and 21 September 1984.

******

The main focus of the supporters of the miners during these weeks was the national conference of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in early September. Wider support from the trade union movement was seen as crucial in the battle to win the strike and beat the Tory government, building on the enthusiasm and militancy that the miners’ strike had inspired.

The period also saw efforts to break the strike dramatically ramped up, with “back to work” campaigns, and increased use of naked brutality in mining communities. There was also the second major dock strike of the year, which encouraged hopes of opening a “second front” against the government.

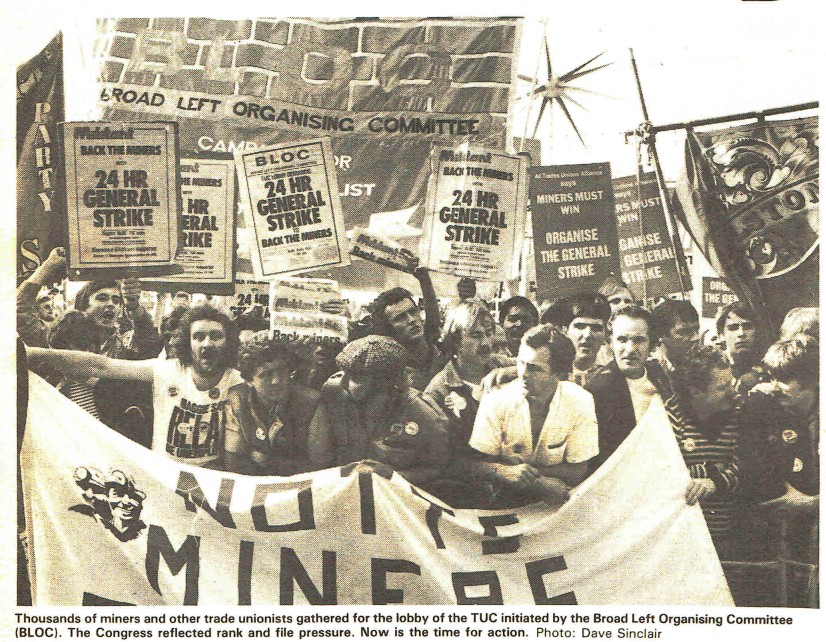

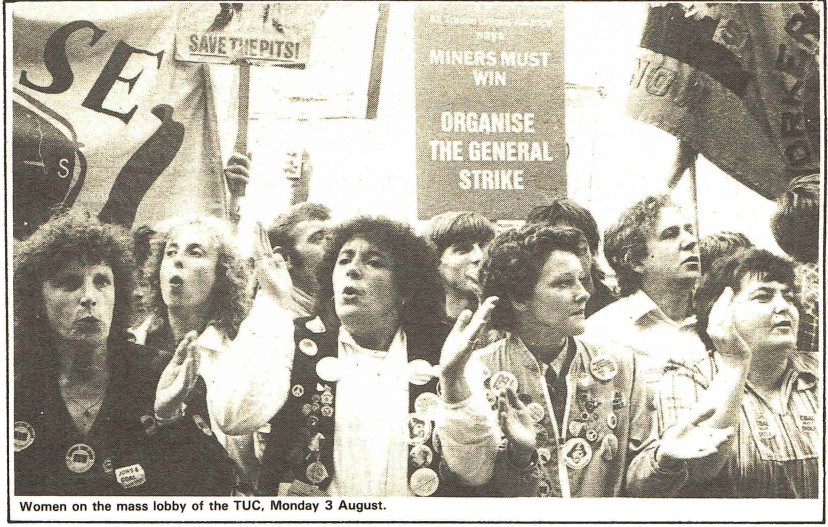

The TUC conference opened on 3 September and was met with a lobby of 10,000 people from the mining communities and their supporters. It was addressed by Kevin Roddy of the National Executive of the CPSA, and Joe Marino, the General Secretary of the Bakers’ Union, both Militant supporters, and Rodney Bickerstaffe of NUPE (now part of UNISON).

[photo Dave Sinclair – Militant 7 Sept]

The lobby had been called by the NUM itself, together with the Broad Left Organising Committee (a new umbrella organisation of left groups in different unions in which Militant supporters played a leading role), the South East Region of the TUC (SERTUC), SOGAT 82 (a printers’ union) and the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions.

No TUC compromise deal

The demonstrators were calling for all unions to support the NUM and respect its picket lines. They also opposed attempts by the right-wing leaders of the TUC, such as the outgoing General Secretary, Len Murray, to take control of the strike as the condition of giving their support. It was feared that if the TUC General Council took control of negotiations, it would put together a “compromise deal” that would sell out the main principle of opposition to the pit closure programme. The TUC leaders were too fond of seeing themselves, not as supporters of the miners, building solidarity, but as neutral “arbiters”.

Another source of suspicion, confusion and frustration before the conference was the talk of “secret negotiations” – again prompting fears of a sell-out. It was essential to insist that any deal was reported back to a special delegate conference of the NUM and voted on.

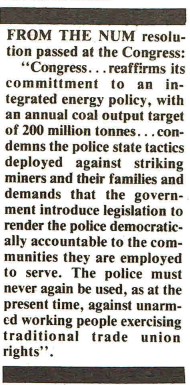

Some unions called on the TUC to organise a 24-hour general strike. These included the National Graphical Association (NGA), a print union already victimised under the Tory anti-union laws in the Stockport Messenger dispute, and the Civil and Public Services Association (CPSA) a forerunner of today’s PCS. One union, the Furniture, Timber and Allied Trades union (FTAT) had a motion to the conference calling for a 24-hour general strike, yet the leaders of the NUM, sadly, did not give it their support.

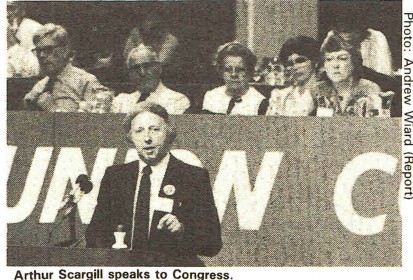

Arthur Scargill’s ovation

In the event, the TUC conference was a morale-boosting triumph for the miners, although the need to match warm words with bold action was widely recognised. The speech from Arthur Scargill electrified delegates, leading to a sustained standing ovation and the outbreak of chants of “Here we go, here we go!”

He pointed out that there were the same number of miners out on strike in September as there were at the start of the strike six long months earlier. He addressed head on the issue of picket line violence. He said that 6,000 miners had been arrested and that: –

“These men are not criminals…Three thousand of our members have been injured. Two are now in intensive care units. Five members have died during the dispute, two on picket lines, two on the way to picket lines, and one whilst working on voluntary safety work in the pit…It is a basic tenet of trade unionism that when workers are on strike, you don’t cross picket lines.”

[Militant 7 September]

Eric Hammond, the leader of the right-wing EEPTU (Electricians and Plumbers Union) made a disgraceful speech nit-picking on details and condemning the main NUM motion for not dealing with “picket-line violence.” He was heckled and almost howled down at points. Within a few years, the EEPTU would become an open scab union, making deals with the Murdoch press to break the print workers’ unions.

Of course, the Labour Leader, Neil Kinnock, when he spoke to the TUC, also prioritised the issue of “violent picketing” rather than the violence of the police against the miners, and stopped short of giving full support to the NUM in a shameful performance.

Significantly, two speeches from relatively moderate trade unions showed clear support for the miners. David Basnett of GMBATU (now the GMB) took an implied swipe at Hammond: –

“We are all against violence no matter where it comes from, but we won’t see the NUM destroyed. We will not see the miners starved back to work. If Thatcher destroys the NUM, she destroys all of us.”

[Militant 7 September]

Gavin Laird, the General Secretary of the Engineers union, the AUEW, said, “We are all at one with the NUM. We will resolve this dispute on the basis of a victory for the miners.”

Weasel words

The conference passed the NUM motion overwhelmingly, together with a “statement” from the TUC General Council. This statement, a result of negotiations between the NUM and the Council, affirmed “total support for a concerted campaign to raise money to alleviate hardship in the coalfields.” It also pledged unions not to move coal or coke or oil substitute for coal or coke across NUM official picket lines. But it also included more weasel words, that

“The practical implementation of these points would need detailed discussions with the General Council and the agreement with the unions directly concerned.”

This was inserted to give the right-wing unions, such as the steel workers’ union, the ISTC, a get-out clause. The TUC conference could pass a motion of solidarity and respecting picket lines, but the actual implementation of that resolution would be bogged down in “discussions” with individual unions. Calls for a 24-hour general strike were sadly defeated, and there was no commitment to a 10p a week levy of all trade union members.

The Conference seemed to mark a clear break from the prevailing ideas of so-called “new realism” among trade union leaders, which represented a move away from “old-fashioned” militancy to a more service-based unionism, recognising, rather than defying, the new anti-trade union laws. A motion from the NGA was passed committing the TUC to support unions that came into conflict with such laws, and condemned its failure to support the NGA in December 1983.

However, an amendment from the AUEW inserted a clause saying that it did not mean the TUC giving automatic support to the actions of an affiliate union. This amendment was narrowly lost but then the vote was held again after lunch, when it was narrowly passed! In effect, the motion was rendered pointless by the amendment! In the heady atmosphere of that Conference, most of the right were not confident enough openly to oppose the new militancy but they contented themselves with sneaky get-out clauses, for future use.

In elections for the General Council there was a marked shift to the left but the right still had a 26-24 majority (previously a 31-20) so they could play a disruptive and limiting role. The conference was concerned that the overall membership of trade unions had fallen by 500,000 in a year, at a time of mass unemployment. It was feared that membership could even fall to less than 10 million.

However, it was away from conference votes, in the day-to-day actions of other trade unionists up and down the country, that the outcome of the strike would be decided. Four unions, the TGWU (transport), NUR and ASLEF (rail) and the NUS (seamen) agreed to coordinate their actions, in the absence of a general strike call.

Picketing of power stations

The TUC decision to give a green light to not crossing NUM picket lines encouraged trade unionists, many in GMBATU, to “black” (ie not deal with) coal deliveries at six power stations. A mass picket of 400 miners was organised of Eggborough power station in South Yorkshire. Power stations did not involve the same complexities as steel plants in terms of any minimum necessary coal supplies. The failure to build unity between miners and steel workers actually saw steel production in July 1984 14.6% higher than in July 1983! [Militant 7 September].

The squeeze on coal-fired power stations, put more pressure on the nuclear power stations. The Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) was keeping nuclear plants open until just before they had to be closed for maintenance, as opposed to the normal practice of closing them a few months before. [Militant 14 September]

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) predicted that the power stations would run out of coal by October. The Times [7 September] reported that the government had bought 12 million candles! The action by miners and the rail unions had reduced the transport of coal by rail from two million tonnes a week down to 40,000. However, one million tonnes a week was being moved by road. [Militant 7 September]

[Militant 21 September]

The economist, Andrew Glyn, writing in Militant [7 September] estimated that the strike was costing the government £100 million a week. The diversion of oil supplies from export to replace diminishing coal stocks had caused a balance of payments crisis. The export of oil in this period had been masking the collapse of British manufacturing. The Times [17 September] reported on divisions in the Cabinet around whether the government could win. Using troops to break the strike risked inflaming the trade unions and increasing solidarity action. The ruling class were in a quandary.

Another dock strike

In late August, morale was lifted by the outbreak of another strike on the docks, triggered by the bosses at Hunterston using scab labour, plus members of the ISTC union, to unload the Ostia, which was carrying coal for the Ravenscraig steel plant. The dispute was about the amount of coal that was to be allowed in to Ravenscraig. The TGWU had agreed to 18,000 tonnes per week, while the bosses insisted on 22,400 tonnes and used scab labour to unload it.

The TGWU dockers walked out and the strike quickly spread over this flagrant breach of previous agreements. All docks in Scotland came out, and nearly all the dockers in Tilbury. Seven out of ten major ports were shut down. Dockers at Grimsby voted not to strike but were then so sickened by the smug Tory gloating that they joined the strike! [Militant 31 August] In September, 60 police escorted 20 dockers to work in Hull, but they could not work as there were no crane drivers. They came out again and the next day only 10 went in [Militant 7 September].

Yet, by mid-September, the dock strike had been called off, with minimal concessions from the bosses, including the same “assurances” to use dockers who were members of the TGWU that they had given back in the last dispute in May and then reneged upon. British Steel even insisted on being allowed to use scabs if TGWU dockers were “unwilling or unable” to work! The quota of steel for Ravenscraig was raised to 22,500 tonnes! It was a great disappointment for the mining communities.

Meanwhile the government was becoming ever more rabid in its condemnation of the miners. Leon Brittan, the Home Secretary, called for more life sentences to be used against miners, as the media raved on about violence! [ Militant 14 September] In fact, this period saw an intensification of the brutal crackdown on mining communities, as the full force of the state was used in a war inside mining villages as part of desperate attempts to break the strike and force small numbers of scabs through picket lines.

All through this period there were frantic efforts to start “back to work” campaigns, with little success as only handfuls of scabs responded. In those areas where many miners were working, the numbers working were grossly exaggerated. 1,800 miners were still on strike in Nottinghamshire, and the “Voice of the Majority” (VOM!) group only produced a small trickle of miners back to work.

At the same time, a South Nottinghamshire strike centre was established to support those miners who were on strike, supported by fundraising from unions, Labour parties and others from all over the country. Kids from the area had a holiday provided by miners in France.

Battlefields in mining villages

The village of Armthorpe in Yorkshire, was turned into a battlefield on August 22, after police smuggled in three masked scabs into the local Markham Main pit in the early hours. This was followed by 1,000 police in full riot gear descending on the village, cruising around, making arbitrary arrests and trying to force their way into the miners’ welfare social club. They gave up after miners successfully stopped them entering.

The NUM then commenced 24-hour picketing, resulting in an early-morning pitched battle and police charging through the streets and into houses and gardens, truncheons flailing. A young miner, covered in blood, was paraded around for 45 minutes before receiving any medical attention.

The village felt as if it were under an occupation involving dozens of police vans, curfews and phone tapping. The local residents responded by refusing to serve police in any shops or pubs and local women abused them in the streets. Further mass pickets were planned. [Militant 31 August]. Similar events took place around the same time around the nearby Hatfield Main pit. The socialist singer, Joe Solo wrote the song “The Day the War Came Home” about it, (click here).

In County Durham, on 24th August, riot police were used for the first time in Easington . 1,000 police escorted one single scab to work as the village was sealed off. In Monkwearmouth, 900 police were laid on to escort six scabs. The villages of Murton and Seaham were sealed off and virtually occupied by police brought in from other areas. All this simply increased the number of miners actively picketing. [Militant 31 August] When Durham women went picketing for the first time, they were kicked, punched and dragged along the ground. [Militant 7 September]

Indiscriminately lifted off the streets

Police, cruising in vans at night, were indiscriminately lifting people from the streets. In Leicestershire, a miner walking home alone was punched out of nowhere by a police officer and thrown over a car bonnet. Another solitary 46-year-old was arrested and beaten for no reason, and denied his blood pressure tablets for several hours until he gave his name. [Militant 7 September].

The Guardian reported [7 September] that a man in Wath-upon-Dearne in South Yorkshire, recovering from a knee operation, was beaten by police, who also smashed his crutches. One group of women were arrested, leaving their small children on the pavement! [Militant 14 September]

Minor offences such as criminal damage or “insulting behaviour”, normally punished by fines, were receiving prison sentences or 3-6 months. A young miner from Fitzwilliam, South Yorkshire, who had been arrested in previous police raids there, was sent to a maximum-security prison, where it is reported that he led the other prisoners in chants of “Arthur Scargill walks on water!” [Militant 7 September].

South Yorkshire local council HGV drivers, on the way to work, who noticed a scab bus being prepared, were followed by police and accused of being “scab spotters” and threatened. This led to their one-day strike on 6 September.

A 16-year-old boy in Hunterston, who was on a Youth Opportunity Programme (YOP) scheme, mending fences, was arrested, even though he had played no part in the picketing. In Ayrshire, even some young kids taking their cycling proficiency exams were interrogated by the police about the movements and activities of their fathers, who were striking miners! [Militant 14 September].

NACODS becomes more radical

Finally, in a vitally important development, the union representing supervisory and safety staff in the coal industry, NACODS (the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers) was becoming radicalised. It had already condemned Len Murray by name, for its lack of support for the NGA when it was victimised under the Tory anti-union laws.

NACODS had voted by 54% for strike action at the beginning of the dispute but failed to get the necessary two thirds majority. They generally lived in mining communities and felt the moral pressure to support their neighbours. They were not going down pits except for essential safety work. But the Coal Board now threatened to stop their pay unless they walked through picket lines, leading for calls for another strike ballot.

If this union were to take strike action themselves, then every single pit would have to stop work, even in those areas where most miners were still working, as no pit could operate without them. It could be a game changer, and guarantee a victory for the miners and their communities.

[NB – Much of the information in this article was taken from Militant issues 31 August, and 7, 14, and 21 September 1984]