The latest in a series of articles by Andy Ford on 80-year anniversaries of WW2 events in the USSR and Eastern Europe.

********

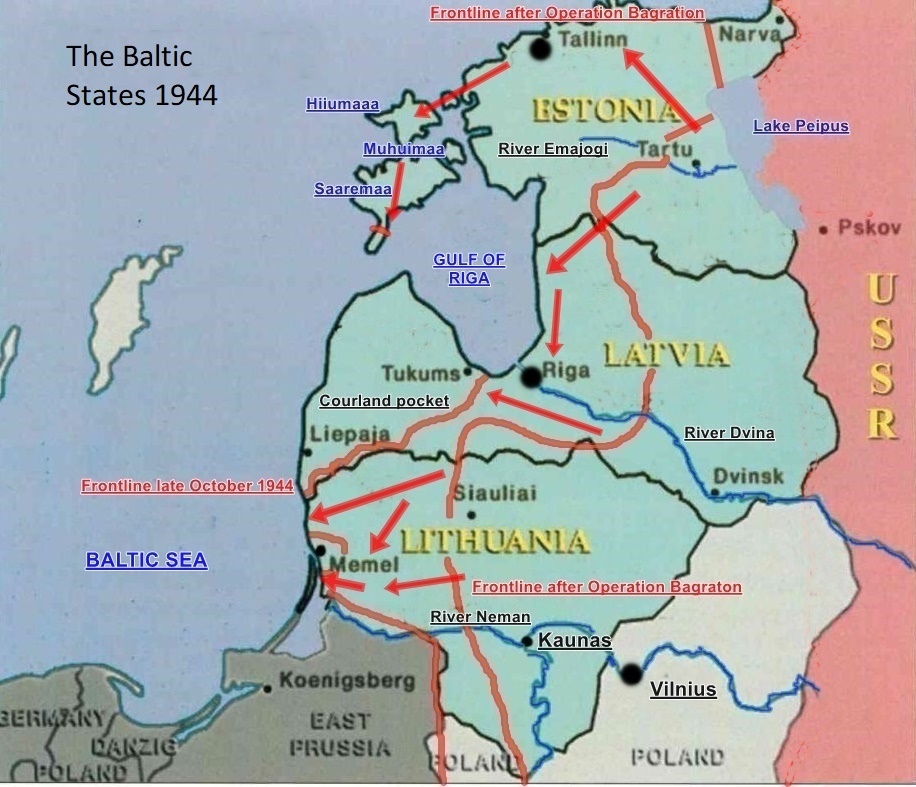

From September to October 1944, the Red Army cleared the Baltic States – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – of the Nazi occupation. But it would be difficult to describe it as ‘liberation’. It was more of a re-occupation, following on from the initial occupation of these states by the Russians in 1940 under the terms of the 1939 agreement between Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

Estonia

The Red Army had been trying, without success, to enter Estonia since February 1944 in what became the Battle of Narva. The Germans were defending a line based on the River Narva in well-prepared positions. To the south of their defences, a large lake, Lake Peipus, formed a natural defence of Estonia against attack from the east and so the Russians were compelled to attack on a narrow front. Quite how formidable the Wehrmacht was in defence, given the time to prepare, is shown in this internal memo describing their ideal anti-tank tactics:

“In the weeks before it moved into the new position, the company used every minute to acquire building material and construct positions. Thus, upon the occupation of the line, all positions, hides, and troop shelters were ready. A thick network of communication trenches connected them to each other. In the few days before the expected tank attack, the troops paid special attention to the improvement and camouflage of the communications that lead to the firing positions.

The position of the 75mm anti-tank gun, which would achieve many kills, lay on a forward slope looking over an open field. In the course of a multi-day defensive battle, the enemy proved unable to uncover this position (located some 250 meters behind the main battle line.)

Right behind the firing position, on the rear slope of the ridge, the anti-tank gunners built a “ready-to-fire shelter” [Feuer-Bereit-Schaft], which was oriented along a line perpendicular, more or less, to the direction of fire. The roof consisted of two thick rows of oak-tree trunks and two layers of packed earth, with a total thickness of one meter. During construction, observers looking from the enemy point of view ensured that the top of this bunker lay below the line of the low earthen walls of the firing position.

The firing position was dug so deeply that the barrel barely rose above the level of the ground. In order to prevent the kicking up of dust when the piece was moved or fired, the anti-tank crew covered both the firing position and the area within a radius of six to eight meters with pieces of sod.

They also made sure to remove all straight lines from the surface of the firing position and the gun shelter. To provide additional camouflage, the route from the firing position to the remainder of the anti-tank company was covered in nets, each five meters long and three meters wide, that were covered with suitable grass and underbrush. So that the gun could be deployed quickly, the track that ran from the gun shelter to the firing position was covered with wooden planks.”

(German Armoured Troops Newsletter, August 1943)

The result of German defensive skills, and the return of the Red Army high command to the inept tactics of 1942 – mass attacks and crude artillery barrages – was a blood bath, and the near total destruction of the historic city of Narva. 480,000 Russian soldiers were killed or seriously wounded at Narva, and the Red Army was still unable to break through. In this one battle, almost unknown today, the Red Army suffered as many casualties as the British army did at the Battle of the Somme in WW1.

Realising their mistake, the Soviet high command switched their focus to the Tartu region, south and west of Lake Peipus. The Soviet 2nd Shock army crossed the River Emajogi on 17th September and smashed German defences, who also relied on the presence of the Omakaitse Estonian militia.

The Germans at Narva were now at risk of encirclement and were forced to withdraw towards Latvia, abandoning the capital, Tallinn on September 22nd. The Germans then successfully evacuated their forces by sea from Tallinn after destroying much of their own heavy equipment and also the Tallinn telephone system, radio station, railway stock and the Old Harbour.

That left the Germans in control of the Estonian archipelago, low-lying islands in the Baltic Sea, just off the western coast of Estonia, which controlled the sea lanes to Leningrad, Helsinki and Tallinn. The Red Army mounted an ambitious amphibious landing from 29th September onwards, using lend-lease amphibious vehicles supplied by the US. Estonian conscripts were employed in the landings and in some places ended up fighting with Estonian SS formations.

The Germans withdrew from the island of Muhumaa almost without a fight, and then from Hiiumaa to the largest island, Saaremaa, which was assaulted by the Red Army on October 5th. The Germans were gradually forced back to the extreme southern tip of the island, where they made a stand as ordered by Hitler, despite the island now having almost no military value to the Germans. Here they held on for several weeks until their commander ordered evacuation, in defiance of Hitler’s orders, on 24th November. German losses in this pointless defensive exercise were around 18,000.

Latvia

The Red Army had originally reached the Latvian Baltic coast at Tukkums on 31st July, as part of the great success of Operation Bagration (see article here), but subsequently the Germans had forced their withdrawal and re-connected their Army Groups North and Centre.

A Russian attack towards the Latvian capital, Riga, on September 15th, was intended to split the two Army Groups once more, but ran into unexpectedly strong resistance. So, in late September the Red Army’s 1st Baltic Front was directed south-west, reaching the coast on the Latvia-Lithuanian frontier.

The 200,000 men of the German Army Group North were now cut off, and retreated from Riga into the Courland peninsula, where they remained bottled up until the very end of the war. Riga fell to the Red Army on October 13th.

Lithuania

Most of Lithuania, including its historic capital, Vilnius, had been taken by Russian forces during Operation Bagration, leaving only its western portion still under Nazi occupation. Soviet general, Ivan Bagramyan, commenced an attack from the central railway junction of Siauliai, towards the German city of Memel (now the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda), on February 5th. The German frontline immediately collapsed, and the Russians drove towards Memel, surrounding it from the north and south by October 9th.

A harrowing 3-month siege ensued as defeated German troops streamed back to the city, which they defended amidst panic-stricken civilians. When the city was eventually abandoned in late January 1945 most of the surviving population, the wounded, and many military formations, had been evacuated by sea.

Memel was the first ethnically German city to be taken by the Red Army, although it had been part of Lithuania from 1919 until 1939. The pattern of settlement in the Baltic region was that the cities were predominantly inhabited by Germans, Jews, and later, Russians, while the rural areas were predominantly Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian. In Latvia particularly, the landowners had been Baltic Germans, even when the region was incorporated into the Tsarist Empire. As Memel had been part of Prussia until 1919, and was mainly inhabited by Germans, Hitler demanded that Lithuania transfer the city to Nazi Germany in 1939. It was his last ‘peaceful’ acquisition.

Stalinist re-occupation

Although the Red Army had cleared the Nazis from the Baltic States, inflicting 60,000 casualties on them at the cost of 30,000 of their own, it could in no way be described as liberation.

For a start, the Stalinist regime had almost no base of support in any of the Baltic countries. The Estonian Communist Party had no more than 150 members in 1944, probably half that in reality. The Latvian Party had a membership of 300 or so, out of a population of 3 million. Only the Lithuanian Communist Party had anything like a reasonable membership of around 3,500.

The Stalinist bureaucracy’s difficulty was made worse by the fact that they themselves had executed hundreds of exiled Baltic communists in the purges of 1937-38. Of the central committee of the Lithuanian Party, only one man survived, and that was because he had been conducting underground work in fascist Lithuania!

It is an even greater irony because Estonia and Latvia had been bastions of Bolshevism in the 1917 Revolution. They had returned some of the highest Bolshevik votes in the elections to the Constituent Assembly in 1918 and had been home to a flourishing Soviet movement.

The position in Lithuania is less clear as it was under German occupation in 1917-18. But, without the intervention of the British navy, who supplied the counter revolutionaries with free weapons and ammunition, and the fascist German Freikorps mercenaries who fought for them, Estonia, Latvia and Finland would have probably joined the USSR on a voluntary basis. All that had been thrown away by 25 years of Stalinist terror and misrule.

Baltic Communists murdered by Stalin – just three examples

In the late 1930s thousands of Communists from the Baltic States – exiled after the successful White counter-revolutions in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – were murdered in Stalin’s purges. This made it exceedingly difficult to build any sort of functioning Soviet state in the Baltics after the USSR re-occupied them in 1944, and the Stalinists had to resort to importing many senior officials from Russia with token figureheads from the native peoples, usually those who had informed on, and lied about, their former comrades in order to avoid the executioner’s bullet.

Here are just three examples of the many thousands of honest communists who met their deaths in the dungeons of Stalin’s NKVD secret police

Jaan Anvalt

Born in Orgau, Estonia in 1884, Anvalt qualified as a teacher, which he combined with Bolshevik political activity from 1905. In 1917 Anvalt led the revolution in Estonia, which actually took place the day before the Russian Revolution in Petrograd and Moscow. He was the Premier of the Soviet government in Estonia and was elected to the 1918 Constituent Assembly at the top of the poll in Estonia.

After the victory of the counter-revolution in Estonia, backed by the British Navy and the German fascist mercenaries of the Freikorps, he was forced to flee to the USSR. He was involved, under the influence of Zinoviev, in the misguided Estonian communist coup in Estonia and after its failure he became first a Commissar in the Soviet aircraft programme. From 1928 he worked in the Comintern. In 1937 he was arrested in the purges, but, refusing to confess to whatever fantastical scheme was put to him, died under NKVD torture in December 1937.

Zigmas Angarietis

Born in Opelupiai, Lithuania, to a landowning family in 1882, Angarietis studied to become a vet. At the age of 15, he turned to socialism and joined the Social Democrats during the 1905 revolution, going on to organise illegal workers newspapers in Lithuania until his arrest by the Tsarist secret police in 1909. Released in 1915 to exile in Siberia, he joined the Bolsheviks in 1916. He participated in the 1917 revolution in Petrograd and was sent to Lithuania in November 1918 becoming the Commissar of Internal Affairs in the first Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic until its overthrow by Lithuanian nationalists, assisted by the Freikorps, in 1919.

Angarietis fled to the USSR where he wrote extensively on the class struggle under feudalism. He edited the Collected Works of Lenin at the same time as editing Lithuanian communist journals and newspapers that were to be smuggled into the country. He lectured at the ‘Communist University for the National Minorities of the West’, and the Lenin School, and was a delegate the Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth congresses of the Comintern. He was arrested as a ‘counter-revolutionary’ in 1938, and was executed two years later, in May 1940.

Ernest Apogga

Born in Libau, (now Liepaja) in Latvia in 1898, he became a factory worker and joined the Bolsheviks in 1917, taking part in the February and October revolutions as a member of the Red Guards. He was then posted all over Russia in the Civil War, successively as Commissar of the Ural Military District, where he fought Kolchak, and then Chief of Staff of the Red Army in the Kuban, dealing with Cossack uprisings in Novocherkassk and the Don region. After the Civil War he was commander of the Moscow Military District and then joined the Red Army military academy.

Latvian Communist

For two years, from 1928, he was Secretary of the USSR State Defence Council and from 1930 until his arrest he was Chief of Military Communications for the Red Army. In 1937 he was suddenly arrested and charged with participating in a ‘Soviet-fascist conspiracy’ (sic), sentenced to death in November 1937 and shot the next day.

Stalinist misrule

In Estonia in 1944, 80,000 fled to Finland, and 25,000 more went to Germany with the departing Nazis. In Latvia 130,000 fled and 120,000 were deported while in Lithuania around 100,000 left the country. Together with the Nazi extermination of the Jewish population, and relocation of the Baltic Germans, the ethnic makeup of all three countries was changed forever by the war.

Stalin had to staff the new Baltic so-called ‘Soviet Socialist Republics’ with imported Russian officials, plus whatever survivors of the 1930s purges he could find, and gradually, a layer of native social climbers who joined the ‘Communist’ Party for whatever gains they could make for themselves.

The situation was made worse by a forced collectivisation of agriculture in 1949 which could only be imposed by sending thousands and thousands of farmers and their families to exile in Siberia, where around a fifth died. As a result of collectivisation farm outputs collapsed. Grain production halved in Latvia, and in Estonia by the 1950s the small private plots which constituted 1.5% of farmed land supplied 42% of agricultural products.

Low level guerrilla war by the ‘Forest Brothers’ in the three countries was only brought to an end in the 1950s by the brutal methods of the NKVD secret police.

Stalinism never achieved anything more than forced acceptance in any of the Baltic States, and in 1989 they were the first republics to break away from the USSR.