By Michael Roberts

This blog was originally published by Michael Roberts on Saturday, 26 October 2024. The original article can be found here. The featured image at the top of the article shows Shigeru Ishiba, the Prime Minister and leader of the LDP going into the election.

**************

Japan holds a parliamentary election on Sunday 27 October. The new leader of the governing Liberal Democrats and now prime minister Shigeru Ishiba has called the election in order to cement his government in office. Previous prime minister Fumio Kishida stood down after a corruption scandal involving ‘slush fund’ money for corporations to fund his party’s campaigns. Nothing new there as it has been standard practice for the LDP to seek secret funding from corporations in return, no doubt, for appropriate policies. The more recent scandal was the close connections between the outgoing Kishida and the so-called Unification Church of the rabid anti-Communist Christian cult of the now deceased Sun Myung Moon.

Disenchantment with the ruling LDP

Opinion polls indicate that while the LDP retains popularity among older conservative voters, younger generations are increasingly disenchanted. Some are looking to the libertarian Nippon Ishin no Kai’s emphasis on political reform and anti-corruption initiatives.

The way the opinion polls are going, the ruling LDP may lose its outright majority in the lower house, meaning it would likely have to rely on its usual coalition partner, the Buddhist Komeito, to control the lower house of parliament. It already depends on Komeito for a majority in the upper house. Komeito has been less willing than the LDP to embrace policies including giving Japan’s military longer-range missiles and removing restrictions on weapons exports that have stopped Tokyo from sending arms to Ukraine or to Southeast Asian nations that oppose Beijing in the South China Sea.

Inflation remains high and real wages not keeping up

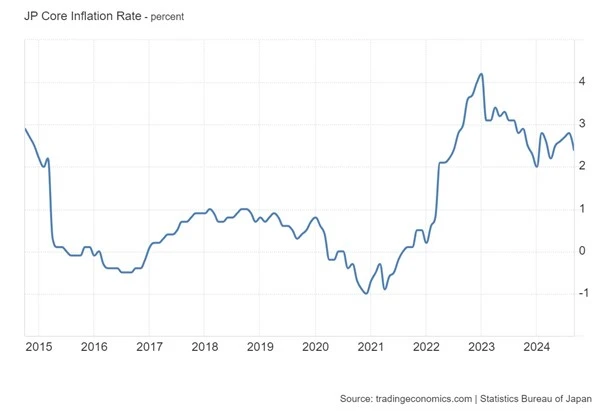

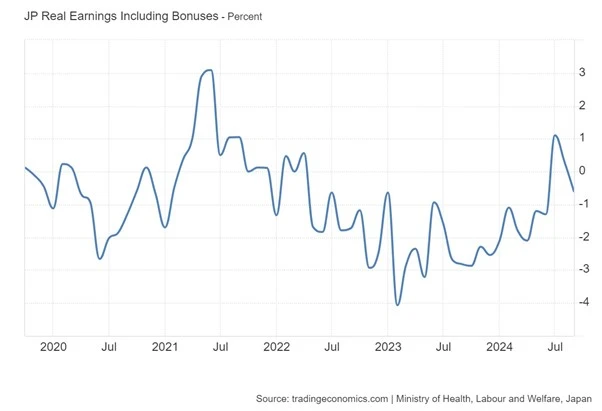

Japan’s anti-China foreign policy in alliance with the US is one thing, but as usual it is the state of the economy that focuses most voters’ minds. For the first times in decades, inflation of consumer goods and services prices has been rising.

Real wages have been falling for two years. Amid rising prices, some opposition parties have argued for a reduction in or the abolition of the sales tax, but Ishiba has pushed back by saying it is an important source of revenue for social security.

Indeed, labour’s share of Japan’s national income has been falling substantially since the end of the Japanese boom period of the 1980s; from 60% to 55% now.

Inequality matches levels in Europe

On some measures, Japan is not so unequal in personal wealth as the other major economies, – the World Inequality Database puts the gini coefficient of wealth inequality at 0.74 (the US is 0.83), and the gini index for inequality at 0.54 (the US at 0.63). But inequality is still significant, with inequality of incomes matching levels in Europe. The top 10% of income earners take a 44% share of personal incomes, while the top 1% have 13%. The bottom 50% of earners get only 17%. As usual, the wealth gap is even greater. The top 10% of wealth holders have 60% of all personal wealth in Japan, a figure unchanged in the 21st century. The top 1% own 25% of all wealth, while the bottom 50% have just 5%. Japan is owned, controlled and run by an elite just as in the other major economies.

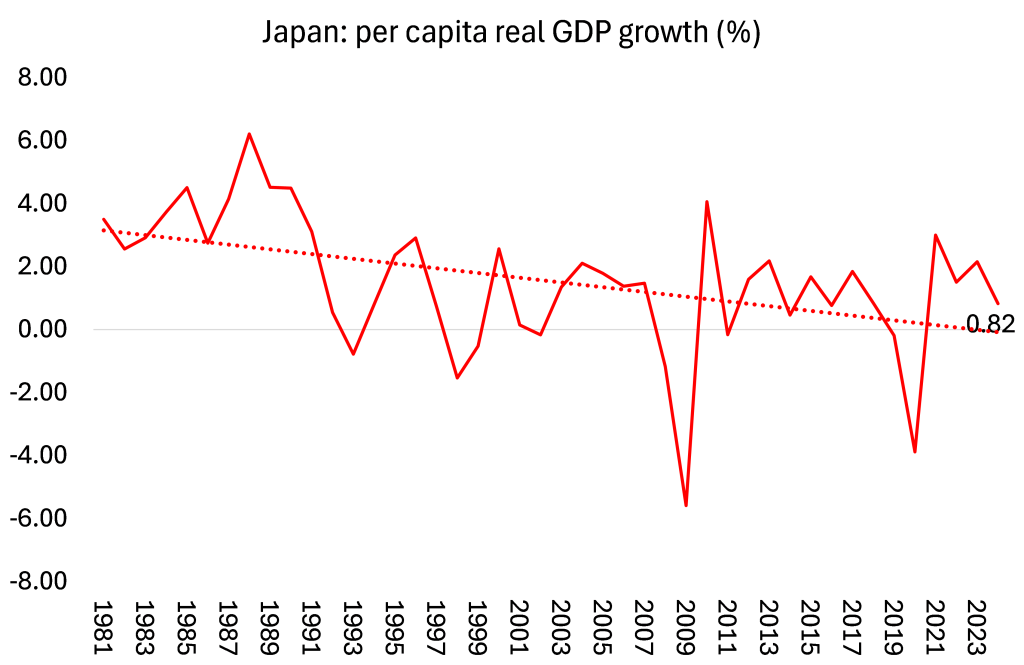

And Japan continues to struggle with years of low economic growth; including during (much heralded by Keynesians) the so-called “Abenomics” under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, which sought to stimulate growth through monetary easing, fiscal deficits and neo-liberal structural ‘reforms’.

‘Abenomics’ and then a ‘new capitalism’

And former PM Kishida won the last election on a program that he claimed was going to revive the Japanese economy with what he called a “new capitalism”, supposedly a rejection of ‘neoliberalism’ as operated by previous PMs like Abe. Instead, he would reduce inequality, help small businesses over the large and ‘level up’ society. This would break with Abe’s emphasis on ‘structural reform’ ie reducing pensions, welfare spending and deregulating the economy.

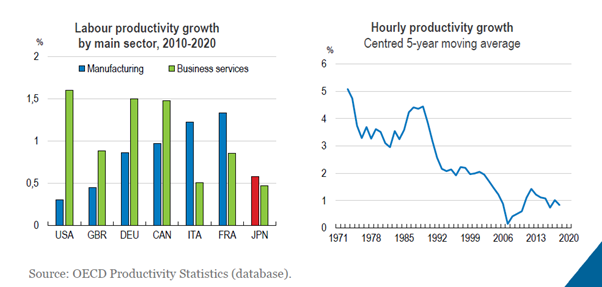

But nothing changed. ‘New capitalism’ did not last long, it seems. Productivity growth remains low. Japanese capital’s image of innovating technology appears to be long gone. A mainstream measure of ‘innovation’ is called total factor productivity (TFP). TFP growth has faded from over 1% a year in the 1990s to near zero now, while the huge capital investment of the 1980s and 1990s is nowhere to be seen. Now Japan’s potential real GDP growth rate is close to zero.

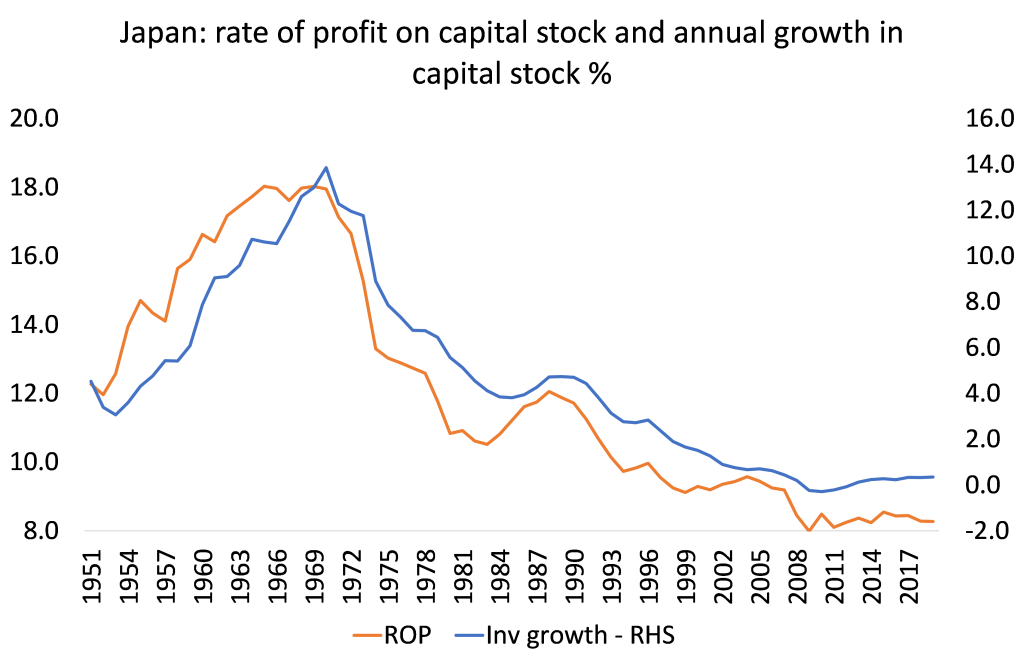

Rate of profit and investment levels remain very low

Even though many Japanese corporates are supposedly “cash-rich”, they are not investing at home. This reflects low profitability in domestic productive sectors. So business investment growth is very weak. Japan’s corporations may have increased profits at the expense of wages and even managed to raise the profitability of capital a little, but they are not investing that capital in new technology and productivity-enhancing equipment. Real investment is no higher than in 2007.

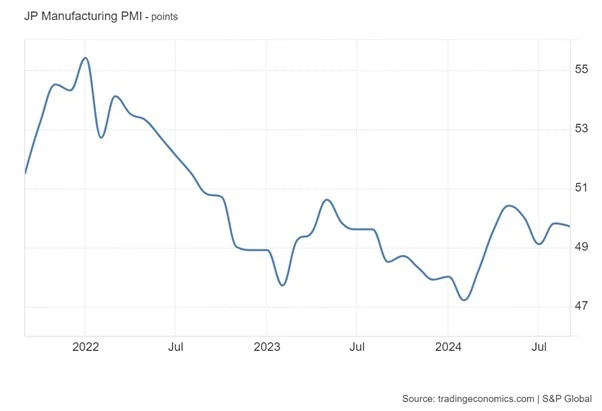

And as elsewhere in the major economies, Japan’s manufacturing sector is in recession (any score below 50 means contraction).

From Abe to Kishida to Ishiba, nothing changes; Japan’s capitalist economy continues to stagnate.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.