By Michael Roberts

The newly elected Labour government’s first budget has just been presented. Rachel Reeves, the UK finance minister (called Chancellor of the Exchequer in Britain) said her budget proposals would stabilise Britain’s public finances; stimulate economic growth, avoid damaging the living standards of ‘working people’; and begin to reverse the disastrous decline in Britain’s public services, including the national health service, education, transport and housing.

And Britain is certainly broken after more than a decade of the previous Conservative government in charge. But can this Labour government deliver any change?

Low productivity growth and investment

Reeves admitted that UK productivity growth and investment is the lowest among the G7. Economic growth has been pitiful, with real GDP rising at under 2% a year for more than a decade. So can we expect a sharp rise in that growth rate over the next five years of a Labour government? Apparently not. According to Reeves, the UK economy will manage an average growth rate, at best, for the rest of this decade of 1.6% a year – so no better than before! As the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) put it in its budget review: “ taken together, the Budget policies leave the level of output broadly unchanged at the forecast horizon.”

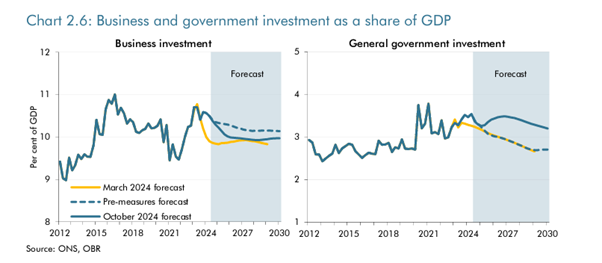

Through the mist of the government claims, the OBR finds that business investment to GDP, the lowest in the G7 at about 10%, will be little changed by the end of this parliament and government investment will not be raised or even stimulate the private sector to invest either.

So the hope for rising productivity growth will be dashed. The OBR expects trend productivity growth (output per hour worked) to rise from zero to 1¼ per cent in 2029. “This is a significant rise from an average rate of ⅔ per cent in the decade following the financial crisis. But it is still well below the average of around 2¼ per cent in the decade preceding the financial crisis.”

The resources available are meagre at best

All this means that the resources available to reverse the decline in living standards and public services are meagre at best and will not repair a ‘broken Britain’.

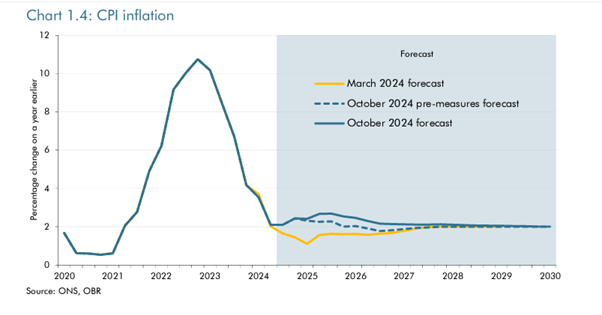

Reeves was keen to say that inflation was coming down and she was sticking to the 2% a year target for the Bank of England. And yet, the projections for inflation would not see that target met until 2029! Indeed, inflation is projected to rise in 2025. So the squeeze on real incomes would remain through this parliament. Indeed, the OBR forecasts that real household disposable income (RHDI) per person, a measure of living standards, will grow by an average of only ½ a per cent a year for the next five years – and that’s an average.

Given a low growth, low productivity economy, all Reeves can do is to try and raise taxes and government borrowing to fund more spending on public services. She has opted to do this by hiking social security contributions paid by employers for each worker they employ. This will supposedly bring in £25bn. Reeves is also raising taxes on capital gains that rich investors pay when they sell their financial assets. And very rich foreigners can no longer claim ‘non-dom’ status to avoid paying tax on overseas earnings if they live in the UK.

No wealth tax on the very rich

But there is no wealth tax on the very rich (which could easily raise £25bn a year); there is no increase in taxation of rapidly rising corporate profits (that stays at 25%) and tax exempt thresholds are not being raised with inflation until 2028, so most working people will pay more tax out of any increase in wages. There will be a “crackdown” on welfare benefit fraud to get £4bn year, but only a vague commitment to tackle widespread tax avoidance and evasion (which loses the government some £25bn a year).

The minimum wage will increase to £12.21. Reeves described the 6.7 per cent increase as a “significant step” towards creating a “genuine living wage for working people” – although it falls short of the £12.60 an hour sum recommended by the Living Wage Foundation.

Reeves modifies Labour’s ‘fiscal rules’ to allow more borrowing

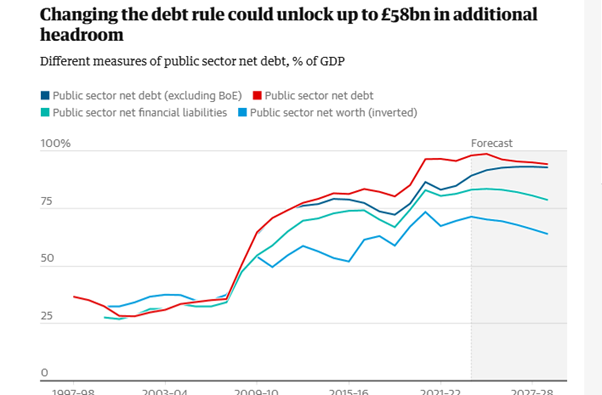

She has also changed what she called the ‘fiscal rule’ on government borrowing. The Labour government is pledged to reduce the public sector debt, now standing at about 100% of GDP. Reeves is ‘remeasuring’ this ‘gross debt’ into ‘net debt’ ie after taking into account government assets like buildings and financial holdings. This will allow her to borrow an extra £50bn through the rest of this decade without increasing the debt level.

The government has decided to borrow more – up £40bn this financial year to fund extra spending on schools, the NHS and the public services. But extra spending on the NHS, housing, transport etc will also be accompanied with £3bn a year boost to the armed forces and a guarantee of paying £3bn a year to Ukraine ‘for as long as it takes’ to defeat Russia.

The impact of the extra borrowing

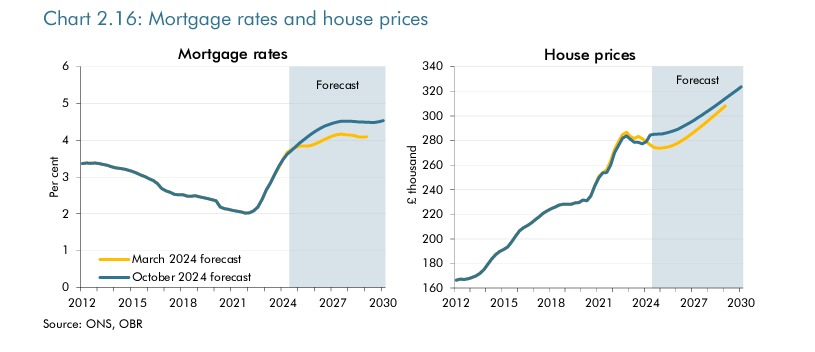

It remains to be seen if the City of London and the bond investors will accept this without selling off government bonds and driving up interest costs. So far, they seem happy. But the OBR reckons that bond yields will rise over the next few years staying above 4%, while the Bank of England rate will only fall from about 5% now to 4%. So mortgage and credit card rates will continue to squeeze living standards.

Thus the government has found some more money to spend on public services, at least compared to what the Conservatives planned – but actually only an increase of 1.5% a year. The general approach is unchanged. It’s up to the capitalist sector to invest and grow. As Sahil Jai Dutta put it: “Labour has shown little sign of changing the current model where critical infrastructure is provided by private firms. Many of these companies have shunned investment for the past three decades, while ramping up dividends, buybacks and executive pay. Rather than confront why, Labour’s priority seems to be sweetening investors and developers with more money available on better terms.” More subsidies for big business funded by more taxes and government borrowing.

No game changer

This budget is no game changer for working people – or for that matter for British capitalism. As the OBR says: “the economic outlook depends on uncertain judgements on the paths for productivity, inactivity, and net migration. The fiscal forecast also remains highly sensitive to movements in interest rates and inflation given the level of debt.”

And all bets are off, if the world economy heads into a slump before the end of this decade.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.