By Ray Goodspeed

[featured photo from RTE]

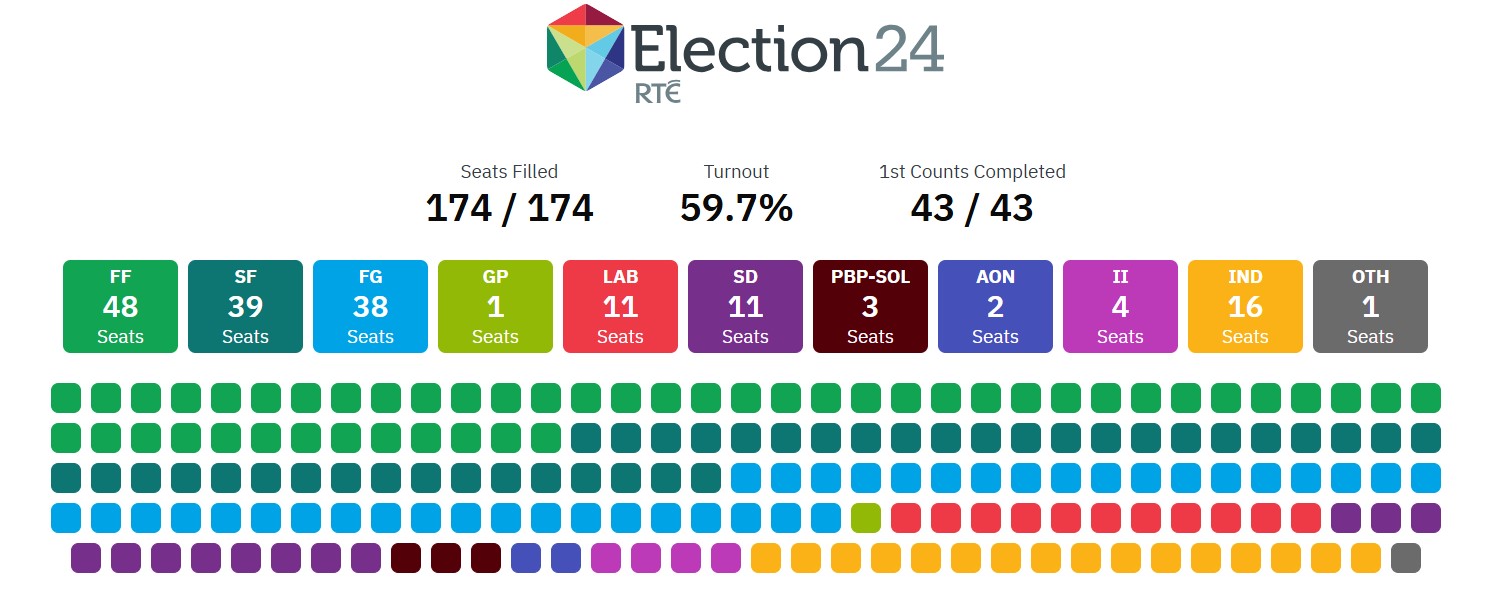

The recent elections in the Irish Republic (29 November) saw Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, the two main parties of Irish capitalism, maintain their position as the likely governing parties, with only a very slight dip in their popular vote. The results were disappointing for Sinn Fein, and especially the Green Party, who had been a coalition partner of main two parties. The overall turnout was just 59.7%, down 2.6% from 2020 and 9% since 2011.

Fianna Fail (FF) and Fine Gael (FG) are just a couple of seats short of an overall majority in the Irish parliament, the Dail, but will probably be able to rely on some random independents, which are much more common in the Irish political system. They received 21.8% and 20.8% respectively, a joint vote drop of less than 0.5%. To some degree this has bucked the recent international trend which has seen incumbent parties from the time of Covid turfed out.

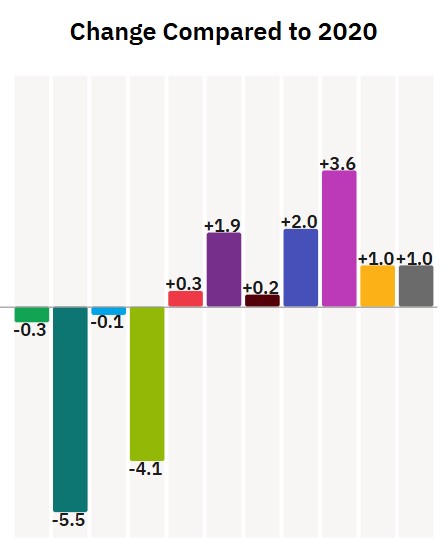

The vote of the main opposition party, the more radical nationalist Sinn Fein, fell by 5.5%, and it came third, on 19%, though it gained one more seat than Fine Gael, due to the complexities of transferred votes between candidates and other parties in the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system. Yet this was a party that just a few years ago was seen as competing for power, with some opinion polls suggesting it might get 36% of the votes.

Sinn Fein built its popularity by positioning itself as a radical, social-democratic party – radical both in economic policy, on the national question, and in terms of social liberalism. Yet, as it came closer to actually achieving power rather than maintaining its former protesting role, it courted more respectability, reassuring international capital that their interests would be protected.

Sinn Fein offered less of an alternative

It distanced itself from popular protests around issues like housing, and would not even rule out working with FF or FG in a coalition! It offered much less of an alternative which could have energised working class voters, and increased the turnout.

Irish Independents, Aontu and Social Democrats – winners

[photo – RTE]

It was the Greens, elected on a “progressive” manifesto, who were punished most by the electorate for propping up a right wing government, losing more than half of their vote (down to just 3%) and all but one of their previous twelve seats. This result is even worse than it looks, as the size of the Dail was increased from 160 TDs (MPs) to 174, as a result of the growth in population.

This is similar to the fate of the Liberal Democrats in the UK who suffered catastrophic losses after propping up Cameron’s austerity government between 2010-15. Voters do not generally like being hoodwinked by fake progressives who can’t wait to get a government job. The Greens, by conceding to FF and FG, not only failed to achieve their own climate targets but did not tackle inequality either. And, by being part of a neo-liberal government, they even discredited some green policies in the eyes of working people.

The election took place against an economic background with contradictory features. The Marxist economist Michael Roberts has a much more detailed article on the Irish economy which can be read here.

On the one hand, based purely on Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Ireland is experiencing a massive boom, based on being a low-tax destination for huge amounts of international capital, especially from the USA.

Modest and slowing real growth

But if you strip out the profits of US multinational corporations, you get what the Irish government call “modified domestic demand”(MDD) – a more realistic measure of the growth of the economy, and this is much more modest and slowing.

Also, the vast amount of wealth sloshing around the Irish economy has not trickled down to the population. On the contrary, it has fuelled an enormous rise in house prices, and in the cost of renting. Homelessness is at record levels, and Dublin contains some of the areas with the highest deprivation in Europe. Irish workers are struggling to cope with the high cost of living, especially energy costs, while the country has high and increasing levels of inequality in incomes and especially wealth. Average income (MDD) per person only reached 2007 levels in 2023!

Throughout the history of the Irish Republic, a capitalist state completely dominated by the reactionary Catholic Church, politics has been reduced to choosing between rival bosses parties, which crystalised in the late 20s and early 30s from the aftermath of the Civil War.

[photo – Wikipedia]

Fianna Fail may have traditionally been slightly more Catholic, more republican/nationalist, or more populist from time to time, just as Fine Gael may have sometimes been more neo-liberal, less Catholic and more moderately republican. But the truth is that they were both parties that, at their core, defended the interests of the rich and the capitalist class.

Lowest ever vote for Fianna Fail/Fine Gael

However, the grip of these two parties has been drastically weakened over the last couple of decades, along with the collapse in support and influence of the Church and the move to more socially liberal policies on abortion and homosexuality. In 2007, these two parties received 69% of the vote between them. Last week, this was down to just 43% – the lowest ever joint total. Since 2020 they have been forced to rule together and the country is abandoning the fiction that these parties present any meaningful choice for workers.

Workers are desperately looking for an alternative, but there is no single workers’ party which plays that role.

Sinn Fein’s radical posturing does undoubtedly provide a pole of attraction for many, sick of the endless Tweedle-dum and Tweedle-dee of FF/FG, and excited by the chance to kick both of them out for the first time in nearly a century. But if Sinn Fein were to come to power running a capitalist Ireland they would end up just replicating the policies of previous governments, because they have no real alternative to capitalism, focussed as they are on the issue of the border in the north of Ireland and Irish unity.

The Labour Party, historically the party of great socialist leaders like Jim Larkin and James Connolly, and which still has seven trade unions affiliated to it, has too often been discredited by its participation in coalition governments with the bosses parties. It has never developed into a mass opposition party. Last week its vote increased by just 0.3% to a total of 4.65%, though it gained five seats in the larger Dail, almost doubling its seats from six to eleven.

Founder of the Irish Labour Party – 1912

[photo – RTE archive]

A much newer party, the Social Democrats, founded in 2015, is socially liberal and seems to have similar policies to Labour. It is not clear, beyond personality issues, why it needs to be a separate party. Its vote rose by 1.9% to 4.8%, very slightly ahead of Labour. It also went up from six seats to eleven.

The STV, proportional voting system is very favourable to small parties and independents. Sixteen independents were elected, with range of political positions and local issues to highlight. Some of these may come to a deal with FF/FG to give them a majority. The vote for independents went up 1%, though they lost 3 seats in the larger Dail.

Left parties

Two left parties – ‘People Before Profit’ and ‘Solidarity’ – associated with the Irish equivalents of the SWP and the Socialist Party in the UK respectively, have previously been able to get TDs elected on the basis of solid local campaigning on issues facing workers, and have played a good role in the Dail, as tribunes, voicing working class protest. Though their overall vote increased very slightly to 2.84%, they got two fewer seats in the larger Dail, due to the vagaries of transfer votes not coming their way in some seats. They now have only three.

Two ex-members of the European Parliament, Clare Daly and Mick Wallace, running as “Independents 4 Change” failed to get elected to the Dail. They are divisive figures on the left, veering towards support for any anti-US figures such as Putin in his war on Ukraine and Assad in Syria, though they have a degree of social media popularity. Their group now has no seats.

The far right have yet to make anything like the gains in Ireland that they have made in many other European countries and the USA and Argentina. But it would be wrong to be complacent. Immigration was an issue in the campaign, although the history of Ireland as an exporter of migrants to other countries makes it harder for far-right groups to capitalise on it.

The role of immigration is also contradictory. There has certainly been a very substantial increase in immigration in recent years, leading to the largest population increase since 2008. This has actually led to higher growth, simply by virtue of more people working and spending, but in the context of widespread inequality and deprivation, particularly in Dublin, where most immigrants settle, the possibility of those on the far-right demonising scapegoats and setting one group of workers against another becomes easier.

You can’t beat the far-right at their own game!

This is especially true as the main parties have made concessions to anti-migrant feeling, particularly around the local elections earlier in the year. This is also true of Sinn Fein and this may have lost it more support among immigrant communities and among younger and/or more radical voters. Making such concessions just reinforces in the minds of voters that immigrants are the cause of the capitalist crisis – and you can never beat the far-right at their own game!

In this election, smaller right-wing parties did make small gains. ‘Independent Ireland’, a new party based on a few defections in the last Dail, gained 3.55% and 4 seats. The right-wing republican party Aontu rose by 2% to 3.9% and got 2 seats. Overall, such right-wing parties got about 8% – a clear warning for the future.

After decades of government by rival bosses parties, Irish workers and young people need a clear alternative to the desperate and worsening problems that they face, based on trade unions and workplaces and campaigns in working class communities and on the vital issue of climate change.