By Michael Roberts

Ascension Mejorado is Clinical Professor and Economics Faculty Chair in the Liberal Studies program at New York University and Manuel Roman taught economics at New Jersey City University, US for over 25 years and is now retired. They have authored a superb book that analyses the US economy from a Marxist perspective and in so doing provides yet more empirical support for Marx’s law of profitability and its essential relevance to crises in capitalist production.

Entitled, Declining Profitability and the Evolution of the US Economy: A Classical Perspective, Mejorado and Roman take the reader on a journey through Marxist crisis theory using the latest data from the US economy.

The main argument in the book about falling profitability

The main argument is stated clearly: “It is our contention, as that of all great economists, including Marx and Keynes, that business profitability drives the accumulation of capital and that at the advanced stages of that process, the system’s growth rate declines because falling profitability saps the incentive to expand the stock of fixed capital assets…. The relationship between falling profitability and the capital accumulation trend is structurally binding.” They show that long-term falling profitability in the US led to corresponding periods of falling capital accumulation rates, periodically punctuated by ‘recessions’ and brief recoveries.

In the decades leading up to the stagflation crisis of the 1970s, declining profit rates undermined the foundations of capital accumulation. In the 1980s, this forced US capital to deindustrialize at home and turn to financial investment. Declining interest rates spurred financial bubbles and paved the way for major financial crises in the 21st century.

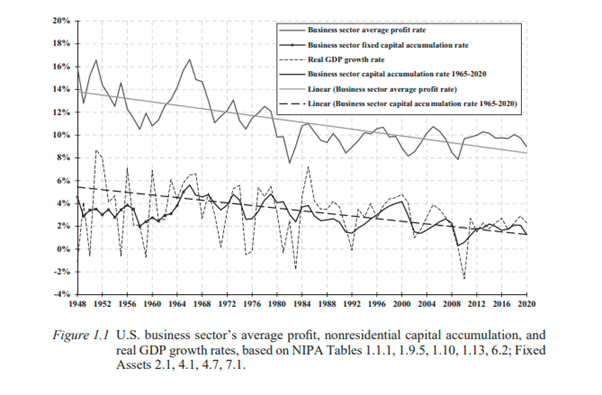

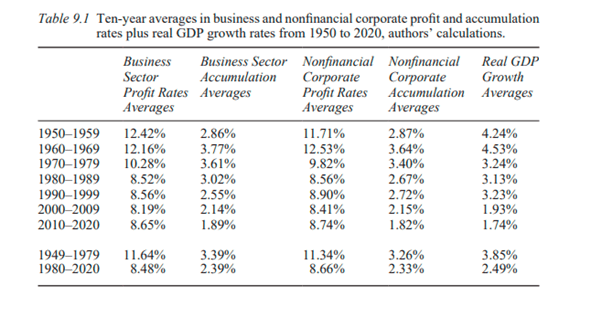

In Figure 1.1 above, from 2001 to 2020, the gross profit rate, defined as business sector net operating surplus on current cost net capital stock, averaged 8.6 percent. At that level, it was 28.2 percent lower than in the first three decades of the postwar period, when it reached a 13 percent average. Similarly, the average rate of capital accumulation in the nonfinancial corporate sector, from 2001 to 2020, at an average of 2.82 percent, was 22 percent lower than in the first three decades of the postwar, when it reached 3.6 percent average.

Most interesting, Mejorado and Roman show that “contrary to the neoclassical conventional wisdom, the Federal Reserve’s policy of lowering interest rates since 1984 had very little effect on nonfinancial capital expenditures.” Indeed, the long-term trend of non-residential capital accumulation in the real economy declined from 1965 to the present. What low interest rates did achieve was a credit-fuelled boom in housing mortgages and household debt that eventually triggered the financial crisis in 2007-8.

Limitations on changes in central bank interest rates

“Raising interest rates to combat inflation will not dampen investment growth if business profitability is high enough as it was in the 1970s, and lowering interest rates will not increase nonfinancial corporate investment when profitability is low or falling as it has been since 2000. Falling interest rates did not spur nonfinancial corporate investment. Instead falling interest rates stimulated mortgage buying by households: there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and the share of disposable income households devoted to the purchase of mortgages.” See also my recent comments on the Fed’s policy here.

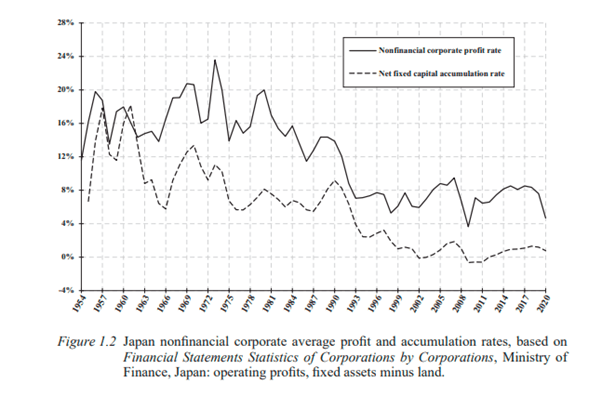

In passing, they take to task Japanese Marxist Takuya Sato’s claim that Marx’s law of the falling rate of profit did not apply to 21st century Japan (Sato wrote this in a chapter of the book, World in Crisis, edited by G Carchedi and myself in 2018).

They find that the relationship between the profitability trend of nonfinancial corporations and the capital accumulation in Japan is highly correlated and this “confirms the existence of a remarkable parallelism between them from 1954 to the year 2020, not a bifurcation in the 21st century. Japan’s economic development confirms the structural links binding profitability and accumulation trends at the higher stages of capitalist development.”

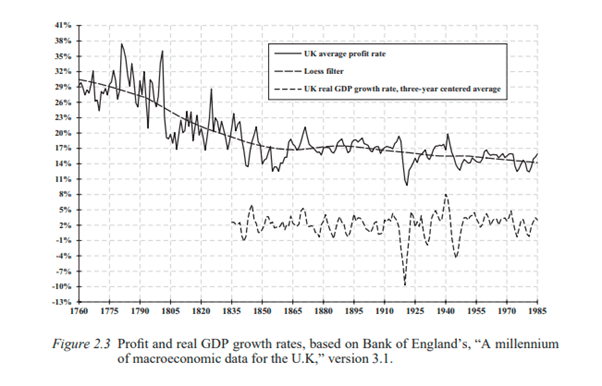

The same story applies to the UK. The authors provide a measure of the rate of profit there back to 1760.

I did something similar in my chapter on the UK rate of profit in World in Crisis.

Mejorado and Roman also reject the idea that the wide gap between the profitability of the top US corporations and the unprofitable ‘zombie’ companies (often referred to on this blog) is the result of monopoly power exerted by companies at the peak of the corporate pyramid. “On the contrary, it is a testimony to their superior competitive power and success in the ever-going race to conquer market share. We interpret the profitability gap in the ‘dual’ economy consisting of superstar firms at one end and zombies at the other as the end result of competition-as-war, not evidence of monopoly power as liberal critics like Stiglitz and Mazzucato insist.” See also this blog I wrote in 2017 about the role of law under capitalism.

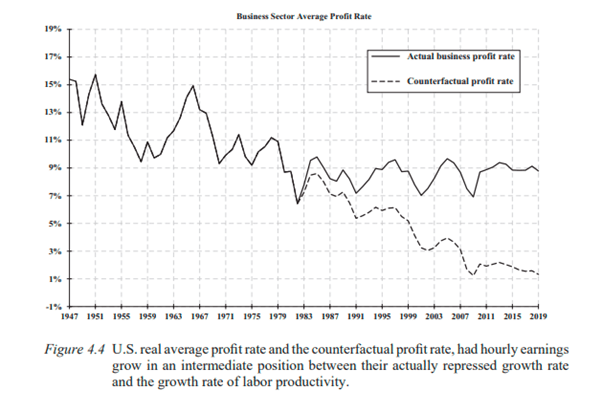

A significant rise in the rate of surplus value under neoiliberalism

Under neoliberalism, there was a major reorientation of capital investments from domestic to offshore manufacturing and the expansion of domestic services created a dual economy with financial trading in the lead. In combination with the compression of wages, neoliberal changes improved business ‘competitiveness’. So there was a significant rise in the rate of surplus value that helped to sustain profitability. To demonstrate this argument, Mejorado and Roman plotted a counterfactual path of would have happened to the average profit rate if wage share in GDP had not been held down as it was after the 1980s. The business sector average rate of profit would have plummeted to unsustainable low levels.

G Carchedi did a similar analysis in his chapter on the US rate of profit in our book World in Crisis (pp49-57).

Analysis of corporate profits in the neoliberal period

In the neoliberal period, the share of corporate profits allocated for purposes other than fixed capital investments sharply increased and, correspondingly, the share directed to finance plant and equipment declined. The share of financial profits relative to all corporate profits rose from less than 10 percent in the late 1940s to nearly 40 percent in 2002 before settling down to over 25 percent in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–2009. This was the reason for the widening gap between the top companies and the so-called zombies.

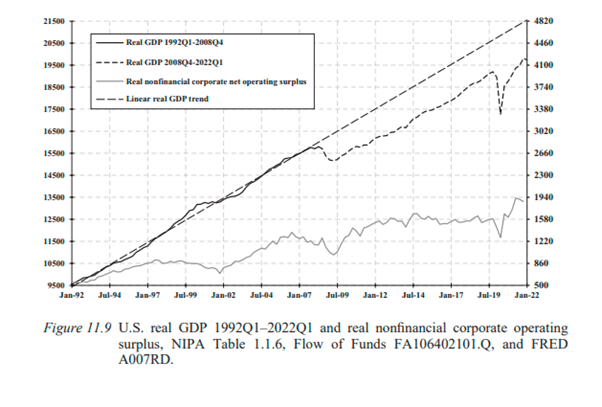

The long-run growth trend in nonfinancial capital accumulation continued to fall throughout the neoliberal phase from the early 1980s to 2001 because US profitability never got back to 1970s levels, let alone the trend levels of the earlier postwar period. In 2001, profitability fell to its lowest trough since the recovery from the Great Recession, and from 2012 to 2019 the mass of real profits in the nonfinancial corporate sector stagnated.

The authors argue that since the 1980s, the diversion of capital to purchase financial assets has contributed to the decline in labour productivity growth and the widening of financial fragility. Falling interest rates led to intermittent bouts of euphoria and inflated financial assets. But rising financial valuations are not sustainable if they transgress the income growth limits of the real sector, as they did in 2007-8. And now significant numbers of so-called ‘zombie’ companies will be in jeopardy if interest rates stay high in response to rising inflation.

A ‘silent depression’ from 2012 to 2020

The authors refer to a ‘silent depression’ in the period from 2012 to 2020 when there was a stagnation of the mass of nonfinancial corporate real profits from 2012 to 2020. This long depression (as I call it) happened because the weak zombie companies were not sacrificed in the Great Recession to benefit overall profitability. Instead “Federal Reserve measures to prop up the banks contributed to the preservation of insolvent ‘zombie’ companies” … Losers can only remain standing as long as central banks provide them with low interest rates and the possibility of accumulating debt. Estimates of the share of ‘zombie’ public companies in the U.S. economy that cannot even meet their interest obligations out of their revenues rose from around single-digit percentage to about 20 percent in 2020.”

Most important, Mejorado and Roman show that it is the movement in the rate and mass of profits that leads to an investment collapse and a hoarding of cash, with the subsequent collapse in ‘effective demand’, not vice versa. “For Marx, an increase in the demand for idle money, at the aggregate level, takes place when the capitalist class as a whole is induced to regard investment and production as not profitable. In this way, Marx linked the analysis of effective demand to the analysis of the fundamental factors underlying capitalist production and growth.”

Differences with the recovery from the Great Depression

The authors compare the restoration of profitability for nonfinancial corporate business after the Great Depression with that of the Great Recession. The profit rate plunged in the 1930s and by 1938 it fell substantially below the level reached in the late 1920s. I have made a similar observation and measurement in a post. But profit rates recovered during the world war and reached historically high levels in the 1940s and remained elevated for 20 years of the ‘glorious’ Golden Age. But that did not happen in the slumps of 2009 and 2020. That’s because there was no ‘cleansing’ of the weak to boost profitability as in the 1930s.

The ‘silent depression is likely to persist

So Mejorado and Roman do not expect the ‘silent depression’ to end. “Given the extended path of secular stagnation, low capital accumulation trends in the real sectors, and the build-up of financial fragility in the banking scaffold that fueled asset bubbles, the depression “is likely to persist” as “a chronic condition of subnormal activity for a considerable period without any marked tendency either towards recovery or towards complete collapse” (quote from Keynes).

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.