As Sir Keir Starmer and Angela Rayner seek to blame bats and newts for delays to major infrastructure and housing projects, TIM HARRIS looks at the importance of biodiversity and asks, “Who are the real blockers?”

Back in 2021, four priority areas were set out in the Tories’ Environment Act: water quality, air quality, waste and recycling, and biodiversity. The parlous state of our rivers and coastal waters received enormous publicity during 2024 and was undoubtedly a factor in the general election result.

The water companies’ shameless dumping of raw sewage into rivers and the sea was one reason many former Tory voters switched to other parties. And this was not surprising, given scale of the problem: there were more than 464,000 raw sewage discharges over 3.6 million hours in 2023.

Amendments lobbied for by environmental charities have strengthened the Water (Special Measures) Bill currently going through Parliament. These include new duties on the toothless regulator OFWAT. But more drastic action is needed now: as a starting point, this must mean nationalising the water companies.

In 2019, it was estimated that 26,000-38,000 deaths in the UK could be attributed to poor air quality, these figures of course disproportionately affecting poorer people. Progress on reducing emissions has “slowed in the last decade” according to a House of Commons briefing paper published in July 2024, with some areas showing “little or no change”. Like so much else, this is the direct result of Tory austerity. The impact of cuts is also borne out in an Office for Environmental Protection report, which bemoans the fact that waste generation and incineration rates have continued to increase, and that recycling rates have stalled.

Human life depends on healthy ecosystems but a combination of factors – primarily climate change, habitat destruction and air, water and soil pollution – are driving continued disruption of these. And this is not just something that happens “elsewhere” but is a real problem in the UK. This is something clearly understood by at least some members of the new Labour government. Soon after the general election in July, DEFRA minister Mary Creagh boasted: “We will deliver a plan to hit the Environment Act targets [protecting 30% of UK land for nature by 2030], halting the decline of species by 2030 … and we will ensure that England’s environmental improvement plan is fit for purpose.” Very welcome news!

Starmer’s Daily Mail soundbite

Alarmingly, however, in his ‘six milestones’ Plan for Change speech on 5 December, Keir Starmer denounced “the absurd spectacle of a £100m bat tunnel holding up the country’s single biggest infrastructure project” – a soundbite taken from the Daily Mail’s headline of a few days previously. Deputy PM Angela Rayner then piled in, saying “Newts can’t be more protected than people”. And Starmer continued, “To the nimbys, the regulators, the blockers and bureaucrats, the alliance of naysayers, the people who say no ‘Britain can’t do this’, we can’t get things done in our country. We say to them – you no longer have the upper hand…”

[Photo Rainer Theuer – Wiki common]

Conflating the need to protect endangered species with ‘nimbyism’ is dishonest at best, playing the populist card at worst. As usual with Starmer, his rhetoric lacked any real content, but the implication is that regulations to protect the UK’s nature need to be relaxed.

This is just a year after Natural England’s State of Nature report described the UK as one of the most nature-depleted countries in Europe, with species abundance having declined on average by 19% since 1970, and even greater declines seen in insect populations. It also reports that “nearly one in six species are now threatened with extinction from Great Britain.” And a Wildlife Trust report states: “Over the last 50 years, nature across the UK has become damaged and degraded, with biodiversity decreasing in abundance decade after decade.”

Culprits named

Of the two ‘culprits’ mentioned by Starmer and Rayner, Great Crested Newts are afforded special protection in the UK because of the scale of their population decline here, which has been driven by the draining of thousands of rural ponds, half of which have disappeared in 50 years. The population is thought to have fallen by a staggering 50% in the period 1965-75 and by a further 2% every five years since. That is why it is unlawful to capture, kill or disturb these amphibians. Incidentally, other species of newt are not afforded protection.

All of the UK’s 18 bat species are fully protected for the same reason – their numbers have declined dramatically as a result of habitat loss, light pollution, persecution and – especially – a massive reduction in their insect food resulting from the use of pesticides and herbicides. This protection has slowed or halted the decline which is a cause for celebration. However, Bechstein’s Bat, the species specifically blamed for holding up HS2’s passage through Buckinghamshire, has a tiny English population of just 1,500. It really is on the brink.

After listening to the Labour leader’s comments, anyone would think that the natural world is the main drag on the UK economy. But the Wildlife and Countryside Link states that land effectively protected and managed for nature has fallen to just 2.93% of England’s total area, down from 3.1% the previous year. Despite all the fine words of politicians, biodiversity continues to crash.

Does this even matter? Yes – it does. Even viewed from a crude materialistic standpoint, the economic benefits – from bees pollinating fruit trees to bats controlling mosquito numbers – are obvious. But Mental Health Foundation research also found that 44% of people interviewed said “being close to nature makes them feel less anxious or worried”.

Location, location, location

Data about the biodiversity crisis should have a bearing on where houses, roads and industry are sited. But it goes without saying that socialists should not be opposed to development. Inexpensive mass-transit public transport – including new rail lines – is something we should all get behind on class and environmental grounds; it enables cheaper travel from A to B and it gets cars off the roads, contributing to cleaner air.

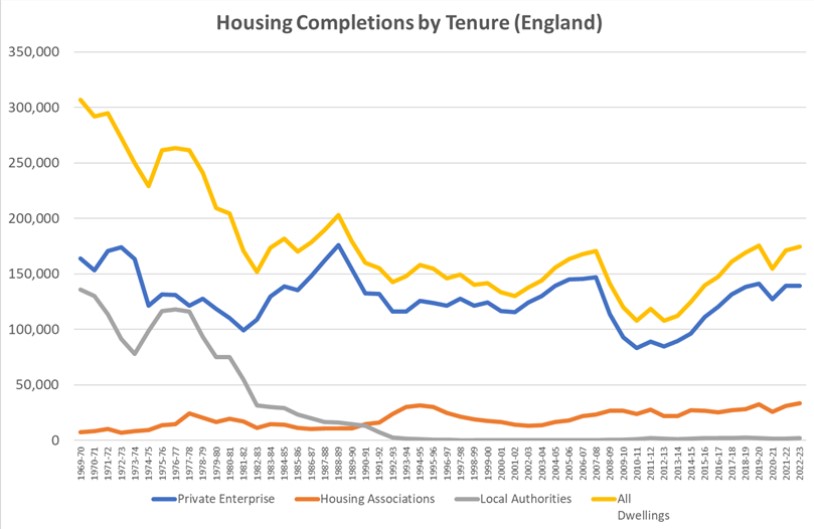

Likewise, there is a need for more housing though, significantly, the government’s goal of 300,000 new homes per year fails to enumerate a target for the greatest need: new, genuinely affordable and rented social housing.

In March 2024, local authority housing waiting lists totalled 1.33 million households, up 18% since 2018. Although numbers vary enormously from authority to authority, in some parts of the country they are astronomical, more than 38,000 in Newham, for example. The average wait for a family-sized home in London is more than six years and even for a one-bed flat it is almost three years. Housing charity Shelter calls for targets for rented social housing and genuinely affordable homes of at least 90,000 a year.

However, I would argue that these targets for new homes and infrastructure are not incompatible with nature recovery – unless regulation is abandoned.

Roots of regulation

Amendments to the Town and Country Planning Act (1990) that came into law early in 2024 tightened up environmental protections, introducing the requirement of Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) and the category of irreplaceable habitat. Ironically, although BNG only made it into law in 2024, the idea was first developed by DEFRA when Gordon Brown was Prime Minister.

This stipulation requires that for all but the smallest new developments, there must be a 10% mark-up in biodiversity compared with the site before development. This increase can either be on-site or traded to another location. Ecologists fear that cut-to-the-bone local planning authorities don’t have the personnel or the necessary expertise to enforce this – only half of local authorities now have an ecologist – but on paper it is a welcome policy.

When a developer submits a planning application, the plans must take account of the environmental quality of the fields, woodland, hedges or water bodies where the building will take place. The presence of rare or declining animals – reptiles, bats, Hazel Dormice, Great Crested Newts and rare birds, for example – must be evaluated by ecologists.

In recent years this process has become more comprehensive and efficient through the introduction of new technology. For bats, this includes infrared cameras and multi-frequency sound recording – but survey work may still take several months if it is to be done properly. For newts, DNA testing of water now shows their presence or absence very quickly.

Rare circumstances

Only in very rare circumstances does the presence of a rare or declining animal species prevent construction. Developers are often required to modify their plans but are usually allowed to proceed, as long as they provide mitigation. This may involve planting trees, placing bird and bat boxes on buildings, or relocating reptiles and newts to safer locations. The costs involved generally pale into insignificance in comparison with the numbers involved with the development itself.

So, is Starmer really saying that this must end? And, if so, how does that square with Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Steven Reed’s statement that this will be “the most nature-positive government this nation has ever had”?

The most protected environmental category – defined as ‘irreplaceable habitat’ – is “very difficult to restore, create or replace once it has been destroyed” according to DEFRA. This may be because its age, uniqueness, species diversity or rarity. Only in “wholly exceptional circumstances” should development take place at such sites.

[photo – HS2]

HS2’s route through Sheephouse Wood, Buckinghamshire, was deemed to be a wholly exceptional project, though many environmentalists argued that its route should be changed to avoid it. Why was it deemed to be such an important site? Its ancient woodland was home to 13 species of bat, including the most northerly colony of Bechstein’s. HS2 agreed to provide a structure over the line as it passes through the wood to avoid collisions with the bats. The structure is highly innovative and created work, so surely should be celebrated. But no, this was apparently an example of “regulators” holding the UK back.

Developing for profit

While there have been particular issues surrounding the HS2 project, the real reasons for housebuilding targets being missed go way beyond environmental regulation. One problem is a lack of labour. The Homebuilders’ Federation recently said that “for every 10,000 new homes built, the sector needs about 30,000 new recruits across 12 trades”. Apparently, while there are enough workers to maintain current levels of about 220,000 new homes a year, there are nowhere near enough for the aspirational increase to 300,000. The Federation cites skills shortages, an ageing workforce and – oh, the irony – Brexit.

A columnist in the January 2025 issue of Birdwatch magazine, perhaps an unlikely source, hit the nail on the head when he wrote: “It looks as though the house-building industry has captured the government already and is having its way smoothed to bigger profits rather than our way smoothed towards more housing for the poor”. Indeed, private developers build to make profits, not out of the goodness of their hearts. If profits aren’t big enough, they simply won’t do it. Their priority certainly isn’t the 90,000 genuinely affordable or social rented homes that Shelter reckons are desperately needed annually.

At the end of 2023 the Competition and Markets Authority calculated that the 11 largest housebuilders owned plots that could accommodate 1.17 million homes across 5,800 sites but were not being built on. About 522,000 had some form of planning permission, another 658,000 did not. This practice of land-banking works on the assumption that prices will rise in future, so it makes sense to delay.

Local authorities must be given the money to build these to the highest possible standard to cut energy usage and eliminate fuel poverty. Although there are many low-value sites in rural areas where housing could be built without a devastating impact on the natural environment (especially with properly enforced Biodiversity Net Gain measures), the countryside charity CPRE estimates that 1.2 million homes could be built on unoccupied brownfield sites.

And then there are the unoccupied homes. The London borough of Lambeth has one of the longest waiting lists in the UK, but Cllr Martin Abrams found that in 2023 there were 2,955 long-term unoccupied private homes that could be used to cut the waiting lists.

And the government should go further and establish a well-funded national house-building service to circumvent the big developers and begin a programme of skills training and building ‘gold standard’ eco-homes for rent in places where they are needed while adhering to the policy of Biodiversity Net Gain.

Over time, rents would help cover construction costs, increased employment would boost tax revenues, sustainable design would reduce emissions and eliminate fuel poverty, and working with ecologists would help boost biodiversity. It really is possible.

[Featured photo shows Sir Keir Starmer (left) and a Bechstein’s Bat – bat photo -Dietmar Nill credit here]