By Michael Roberts

I have long been sympathetic to the concept of long cycles in capitalist production and accumulation. This is the idea that capitalist production moves in cycles, not just in booms and slumps every 8-10 years or so, but also there are longer periods of generally faster accumulation and output growth ie periods of relative prosperity followed by a periods of relatively slower accumulation and growth, with more recessions. These longer cycles or waves last around 50-60 years including the upswing and downswing.

If such cycles exist and can be supported by empirical evidence, they would provide an important indicator of the state of world capitalist economy. For example, if capitalist economies are in a long upswing of production, investment and profitability, as they were after WW2 up to the late 1960s, then the prospects for any radical or revolutionary change would be low – capitalism was working. On the other hand, if the world economy had entered a downswing in production, accumulation and profitability, that would create new class tensions that could bring about radical changes (for example, from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, eg with the overthrow of military dictatorships across southern Europe).

The long cycle analysis from Nicolai Kondratiev

The most famous long cycle analysis is attributed to Nicolai Kondratiev, a Russian economist of the early 20th century. He argued that in all ‘probability’ such long cycles existed and he sought to reveal them empirically, primarily by relying on the movements in prices of commodities, which in turn depended on long term investments in infrastructure and in markets. Kondratiev argued that such cycles were ‘endogenous’, ie they were internal or driven by economic forces within capitalism.

Kondratiev was strongly criticised for his ‘mechanistic’ approach – the most famous critic being Leon Trotsky, who, while recognising the compelling features of Kondratiev’s claims, rejected that these cycles, if they existed, were economically endogenous, arguing instead that political and social forces, like wars and revolutions, were major contributors to any significant changes in the direction of capitalist development. Later, a close follower of Trotsky, the Belgian Marxist economist Ernest Mandel also recognised long cycles or waves. But he curiously argued that while the upwaves and downphases in the long cycle were due to economic changes (ie endogenous), the downphases only came to an end because of political events (war, revolution etc) and not because of economic changes.

New book on long cycles

I say all this because there is a new book out that looks at long cycles and economic growth with the latest data and seeks to identify these long cycles in capitalism. The authors are the Greek Marxist economists, Nikolaos Chatzarakis, at the New School for Social Research in New York; Persefoni Tsaliki Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and Lefteris Tsoulfidis at the University of Macedonia.

In their book, Economic growth and long cycles, the authors critically evaluate the existing mainstream growth models and offer an alternative approach to the theory of economic growth based on what they call classical political economy, but in essence is a Marxist approach. They argue that capitalist development takes the form of “long periods of expansion characterized systematically by accelerating growth rates and other periods of similar longevity during which growth decelerates and sometimes becomes negative.”

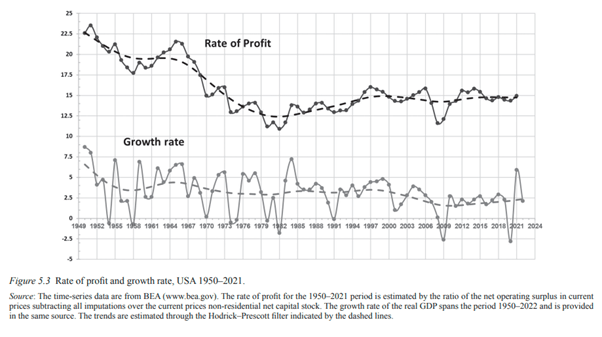

Their model shows that “economic growth is a turbulent but non-erratic and indeterminate process” in which two distinct patterns become apparent: the long-run tendency of capitalism to grow and the cyclical nature of this growth. The cause of the long cycles depends ultimately by the long-run falling tendency of the rate of profit “which gives rise to the cyclical nature of capitalist growth.” It is the evolution of the surplus value and the rate of surplus value that ultimately shapes the evolution of the capitalist economy, as opposed to mainstream theories based on investment, consumption or productivity.

Their growth model joins the three basic laws of Marxist economic theory: the law of value; the general law of accumulation (along with the schemes of expanded reproduction) and the law of profitability. This combination of the three basic laws is something that I emphasised in my own work on crises (see Marx 200). When combined, the empirical results closely follow the actual evolution of the capitalist economy in long cycles. Based on these laws, they build a model of economic growth and long cycles consisting of five differential equations based on: the evolution of the rate of profit, investment in both constant (fixed) and variable capital, technological change and capital devaluation.

Five long waves since 1834

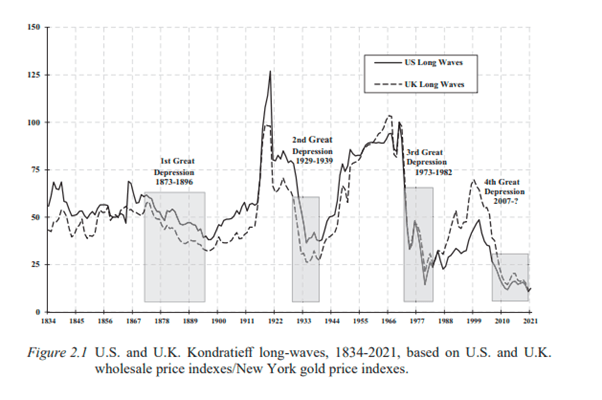

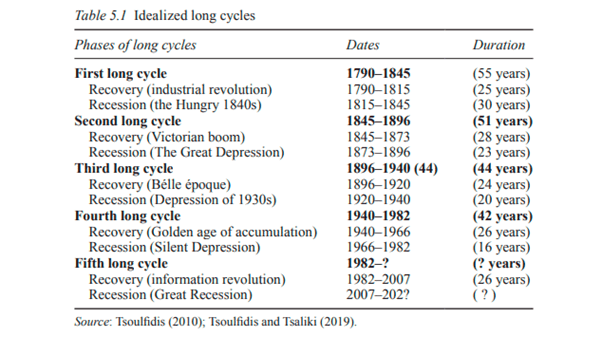

The authors find that there are five long waves or K-cycles spanning 187 years of capitalist development in the US and the UK, from 1834–2021.

These waves match earlier work by Anwar Shaikh’s (in his book Capitalism (2016) p66 and as early as 1992). I also constructed a long wave or cycle model in my book, The Long Depression, pp. 217-34, although the dates of my cycles were different from the authors, as they make the period of profitability downturn in the 1970s as the downphase of a fourth K-cycle, thus entering a fifth K-cycle from 1982 to now. For more on the differences between my view and that of the authors, see this.

The authors’ empirical evidence importantly connects their cycles to long-term changes in the trajectory of the rate of profit. “During the upward stage of the long cycle profitability is rising, and businesses have no compelling reason to risk their already good performance by introducing radical innovations. By contrast, in the downturn phase of the long cycle, profitability is stagnating or even falling, and the prospects are bleak, which challenges the very survival of the enterprise. Under these circumstances, the pressure to innovate is at its highest as capitalists, on the one hand, face the abyss of default; on the other hand, their higher likelihood for survival compels them to assume the risk of becoming more innovations-prone and, therefore, opt for the innovation path.”

The authors claims for their analysis

Thus the authors claim that their analysis of long cycles integrates the Schumpeterian view on innovations and the theories of social structures of accumulation (SSA) into a single and unified theory in which the ‘cause of the causes’ is the evolution of the rate of profit. It is the cumulative long-run effect of the rate on investment and on the mass of real net profits that, past a point, generates the conditions for the manifestation of economic crisis and the change in the phase of economic activity.

The authors argue that “For Marx, the crises in capitalism have intrinsic causes and, therefore, are not conjectural; in this sense, they are inevitable.” The evolution of the US economy follows the Kondratiev’s theoretical scheme and the movement of the rate of profit inevitably shaped it over the post-WWII period.

The technical aspects of the model are detailed in a chapter that conveys both the secular and the cyclical patterns in the evolution of capitalism in which profitability governs capitalists’ decisions to expand or contract, hence shaping both the tendential and the cyclical patterns of the system’s behaviour.

The authors interestingly argue that the growth rate of the rate of surplus value becomes the key explanatory variable of the upswings and downswings of the rate of profit for two reasons: first, it formulates the degree and level of disproportions between the departments of consumption and investment and; second, it defines the system’s ability to generate enough new surplus value at each phase of the accumulation process. “By so doing, the rate of surplus value becomes the principal variable determining the rate of capital accumulation and, to the extent we know the literature, this particular role has not been adequately explored.” Indeed, this is a new insight.

The point of ‘over-accumulation’

As the authors correctly emphasis, a falling rate of profit is not “in and of itself” capable of generating crises. In fact, if the fall in the rate of profit is slow enough, the economy can keep expanding for many years. What is required is an underlying cause that takes the ‘possibility’ to pass into the ‘actuality’ of crises (see my paper, Tendencies, triggers and tulips.) Such a cause is offered by Marx in the trajectory of the mass of realized surplus value (profits). As the rate of profit declines, there is a point at which the mass or real net profits stagnate and thereafter even falls. This is what can be called ‘Marx’s moment’ or point of ‘over-accumulation’. At this tipping point, the capitalists abstain from investment, and the system spirals down into a crisis.

The authors provide us with new evidence of the existence of long cycles and in so doing offer us an important indicator of the long-term ‘health’ of capitalism in the 21st century. According to the authors’ analysis, the fifth K-cycle should end by the end of this decade (see table above).

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.