By Michael Roberts

Ukraine: a human disaster

Today marks the end of the third year of the Ukraine-Russia war. After three years of war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused staggering losses to Ukraine’s people and economy. There are various estimates of the number of Ukrainian civilians and military casualties (deaths plus injuries): 46,000 civilians and maybe 500,000 soldiers. Russian military casualties are about the same.

Millions have fled abroad and many more millions have been displaced from their homes within Ukraine. A confidential Ukrainian assessment earlier in 2024, reported by the Wall Street Journal, placed Ukrainian troop losses at 80,000 killed and 400,000 wounded. According to government figures, in the first half of 2024, three times as many people died in Ukraine as were born, the WSJ reported. In the last year, Ukrainian losses have been five times higher than Russia’s, with Kyiv losing at least 50,000 service personnel a month.

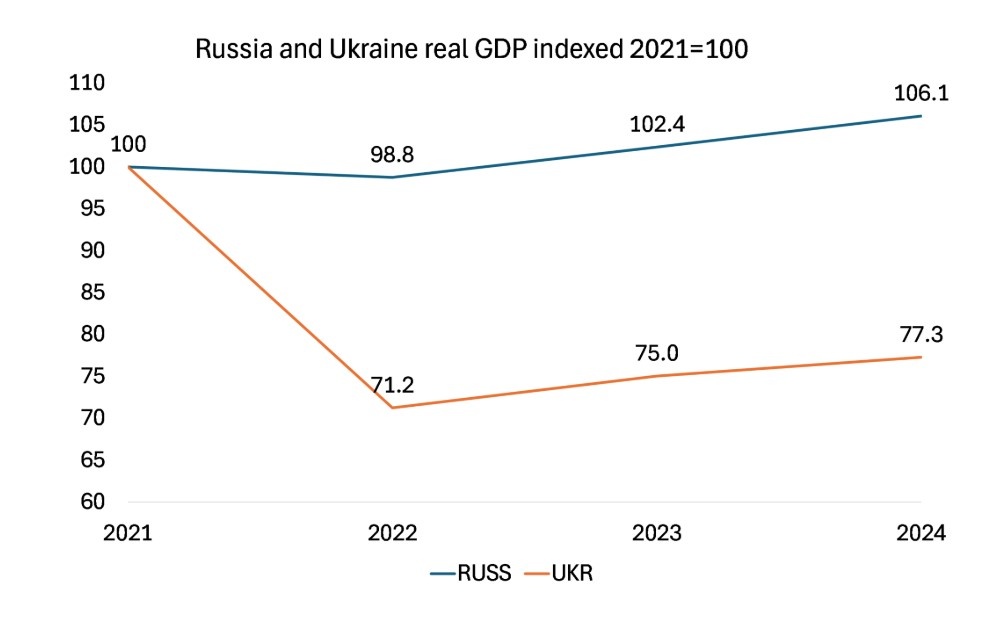

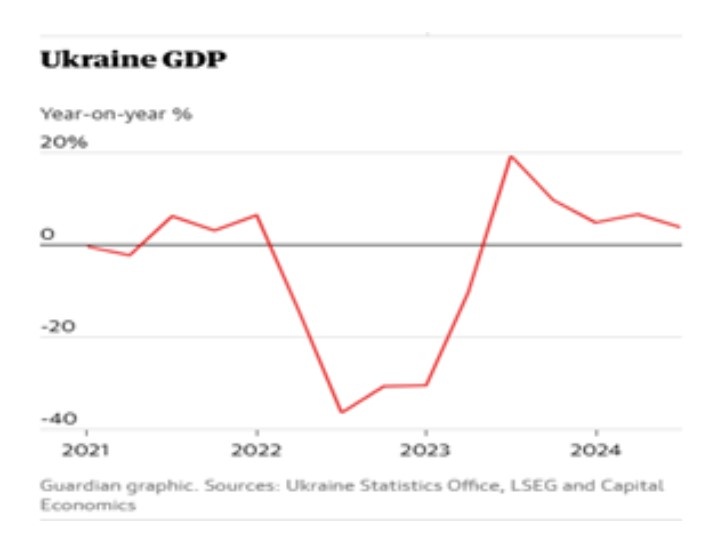

Ukraine’s GDP is down 25% and an additional 7.1 million Ukrainians now live in poverty.

The damage to those staying in Ukraine is immense. Learning losses by Ukrainian children are a particular worry: Ukraine will end up with lower quality additions to its workforce due to war-caused (and prior to that, Covid-caused) disruptions in the learning process. These losses are estimated to be in the order of $90 billion, or almost as much as the losses in physical capital to-date.

Studies also show that a war during a person’s first five years of life is associated with about a 10% decline in mental health scores when they are in their 60s and 70s. It’s not just war casualties and the economy that’s the problem, but also the long-term damage to those Ukrainians staying.

Despite the war, there has been some modest economic recovery in the last year. Energy exports have jumped. Ukraine’s ports on the Black Sea are still functioning and trade is flowing west along the Danube, and to a lesser extent by train. Meanwhile, agriculture has staged a recovery. Even so, manufacturing of iron and steel still remains at a fraction of its prewar level; down from 1.5m tonnes a month before the war to just 0.6m a month.

But Ukraine badly lacks able-bodied people to produce or to go to war. Ukraine’s unemployment rate was 16.8% in January, but that still leaves a shortage of workers because skilled people have left the country and most others have been mobilised into the armed forces. So bad is the situation that there has been talk of mobilising 18-25 years olds who are currently exempt, but this is highly unpopular and would reduce civilian employment even more.

Ukraine is still totally dependent on support from the West. It needs at least $40bn a year in order to sustain government services, support its population and maintain production. It is relying on the EU for such civil funding, while relying on the US for all its military funding – a straight ‘division of labour’.

In addition, the IMF and World Bank have offered monetary assistance but, in this case, Ukraine has to show it has ‘sustainability’, ie it is able at some point to pay back any loans. So if bilateral loans from the US and EU countries (and it is mainly loans, not outright aid) do not materialise, then the IMF cannot extend its lending programme.

That brings us back to what will happen to Ukraine’s economy, if and when the war with Russia comes to an end. According to the latest estimate of the World Bank, Ukraine will need $486bn over the next ten years to recover and rebuild – assuming the war ends this year. That’s nearly three times its current GDP.

Direct damages from the war have now reached almost $152 billion, with about 2 million housing units – about 10% of the total housing stock of Ukraine – either damaged or destroyed, as well as 8,400 km (5,220 miles) of motorways, highways, and other national roads, and nearly 300 bridges. About 5.9 million Ukrainians remained displaced outside of the country and internally displaced persons were around 3.7 million.

What is left of Ukraine’s resources (those not annexed by Russia) have been sold off to Western companies. Overall, 28% of Ukraine’s arable land is now owned by a mixture of Ukrainian oligarchs, European and North American corporations, as well as the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia. Nestle has invested $46 million in a new facility in western Volyn region while German drugs-to-pesticides giant Bayer plans to invest 60 million euros in corn seed production in central Zhytomyr region.

MHP, Ukraine’s biggest poultry company, is owned by a former adviser to Ukrainian president Poroshenko. MHP has received more than one-fifth of all the lending from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in the past two years. MHP employs 28,000 people and controls about 360,000 hectares of land in Ukraine — an area bigger than EU member Luxembourg.

The Ukrainian government is committed to a ‘free market’ solution for the post-war economy that would include further rounds of labour-market deregulation below even EU minimum labour standards i.e sweat shop conditions; and cuts in corporate and income taxes to the bone; along with full privatisation of remaining state assets. However, the pressures of a war economy have forced the government to put these policies on the back burner for now, with military demands dominating.

The aim of the Ukraine government, the EU, the US government, the multilateral agencies and the American financial institutions now in charge of raising funds and allocating them for reconstruction, is to restore the Ukrainian economy as a form of special economic zone, with public money to cover any potential losses for private capital. Ukraine will also be made free of trade unions, severe business tax regimes and regulations and any other major obstacles to profitable investments by Western capital in alliance with former Ukrainian oligarchs.

Ukrainian sources estimate the cost of restoring infrastructure: financing the war effort (ammunition, weapons, etc.); losses of housing stock, commercial real estate, compensation for death and injury, resettlement costs, income support, etc.) and lost current and future income will reach $1trn, or six years of Ukraine’s previous annual GDP. That’s about 2.0% of EU GDP per year or 1.5% of G7 GDP for six years.

By the end of this decade, even if reconstruction goes well and assuming that all the resources of pre-war Ukraine are restored (ie eastern Ukraine’s industry and minerals are in the hands of Russia), then the economy would still be 15% below its pre-war level. If not, recovery will be even longer.

Russia: the war economy

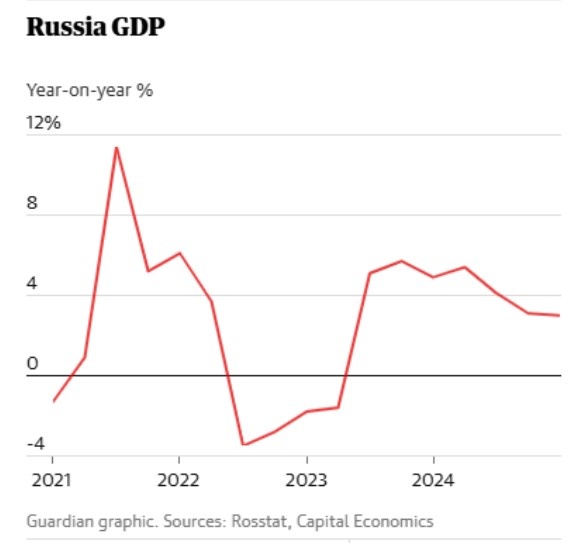

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 to take over the four Russian-speaking provinces in the Donbass in eastern Ukraine has ironically given a boost to the economy. In 2023, real GDP growth was 3.6% and over 3% in 2024. Russia’s war economy is holding up.

Over the past three years of war, Russia has managed to steer through sanctions, while investing nearly a third of its budget in defence spending. It’s also been able to increase trade with China and sell its oil to new markets, in part by using a shadow fleet of tankers to skirt the price cap that Western countries had hoped would reduce the country’s war chest. Half of its oil and petroleum was exported to China in 2023. It became China’s top oil supplier.

Chinese imports into Russia have jumped more than 60% since the start of war, as the country has been able to supply Russia with a steady stream of goods including cars and electronic devices, filling the gap of lost Western goods imports. Trade between Russia and China hit $240 billion in 2023, an increase of over 64% since 2021, before the war.

However, the war has intensified an acute labour shortage. Like Ukraine, Russia is now desperately short of people – if for different reasons. Even before the war, Russia’s workforce was shrinking due to natural demographic causes. Then at the start of the war in 2022, about three-quarters of a million Russian and foreign workers, the middle class in IT, finance, and management, left the country.

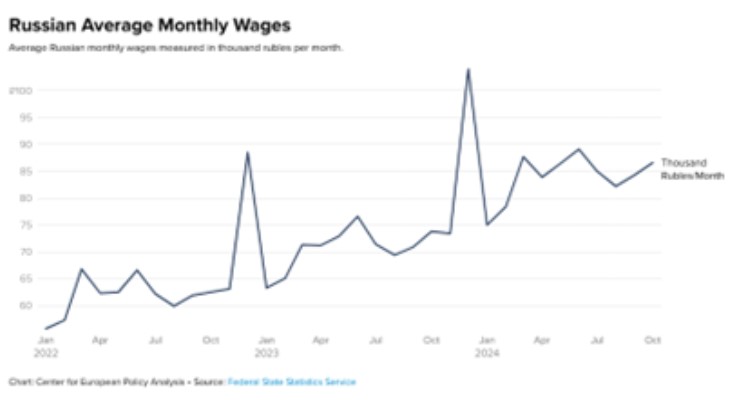

Meanwhile, the Russian army is recruiting tens of thousands of working-age men. Somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 workers join the army every month, about 0.5 percent of the total supply. That has benefited those Russian workers not in the armed forces with security of employment as managers are reluctant to let anyone go.

Wages have soared by double digits, poverty and unemployment are at record lows. For the country’s lowest earners, salaries over the last three quarters have risen faster than for any other segment of society, clocking an annual growth rate of about 20%. The government is spending massively on social support for families, pension increases, mortgage subsidies and compensation for the relatives of those serving in the military.

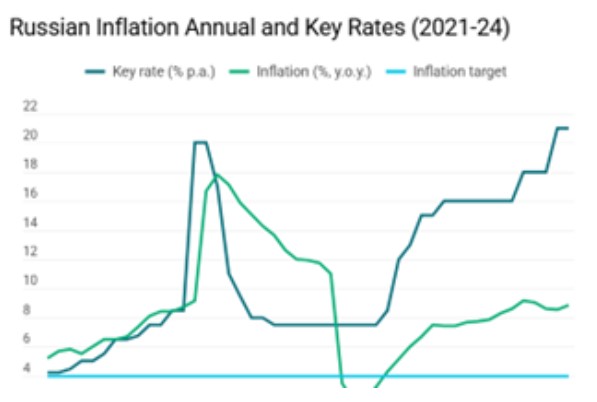

But inflation has spiralled and the ruble has depreciated significantly against the dollar, forcing the Russian central bank to hike its interest rate to over 20%.

A war economy means that the state intervenes and even overrides the decision-making of the capitalist sector for the national war effort. State investment replaces private investment. Ironically, in Russia’s case this has been accelerated by Western companies’ withdrawal from Russian markets and by the sanctions. The Russian state has taken over foreign entities and/or resold them to Russian capitalists committed to the war effort.

Spending on new construction, higher-tech equipment, new kit has hit a 12-year high of 14.4 trillion rubles ($136.4 bn), up 10 percent from the previous year. Investment growth rate topped the GDP growth rate by a wider margin than at any point over the previous 15 years, according to the Moscow-based Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-term Forecasting.

The main destinations for the country’s hitherto-unseen investment are import substitution, eastward infrastructure, and military production. Mechanical engineering, which includes manufacturing finished metal products (weapons), computers, optics and electronics, and electrical equipment, is one of the fastest-growing areas for investment.

Many Western economists are forecasting a collapse in the Russian economy – as they have been saying for the last three years. The acute labour shortage, persistent and rising inflation caused by soaring military expenditure and ever-tightening sanctions will – it is claimed – finally bring about an economic crisis that will force Moscow to abandon its aims in Ukraine and bring about an end to the war on terms more acceptable to Kyiv and its allies.

Many analysts have attributed these signs of overheating to elevated spending on the war in Ukraine, pointing to record-high military expenditure which is expected to have reached over 7% of GDP in 2024. With defence spending expected to rise by nearly 25% this year, accounting for around 40% of federal government expenditure, some have raised the prospect of Russia slipping into ‘stagflation’, combining high inflation with low to no growth.

But despite fighting the most intense war in Europe since 1945, Moscow has managed to fund the war with modest budget deficits of between 1.5–2.9% of GDP since 2022. As a result, the Kremlin has barely had to borrow to fund the war. Tax revenues generated by domestic activity have soared since the war began.

At around 15% of GDP, Russia has the smallest state debt-to-GDP ratio of the G20 economies. So, despite being cut off from most external sources of capital, Russia remains more than capable of financing domestic investment and government expenditure with its own resources.

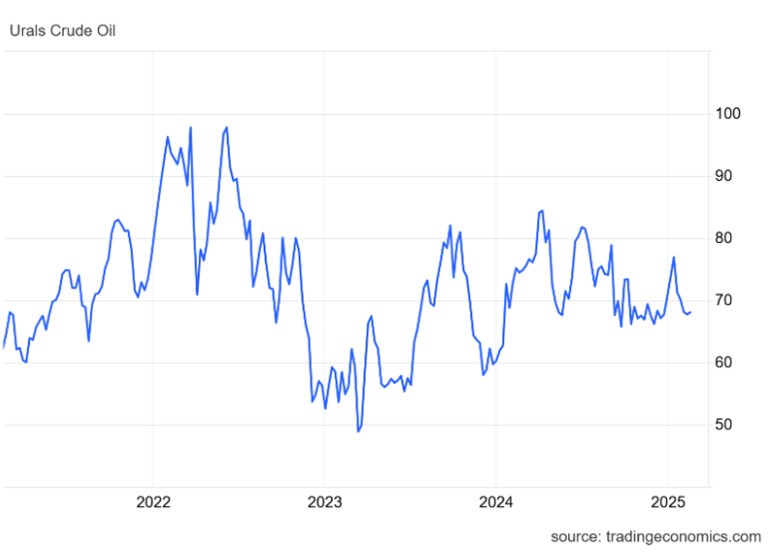

Over the past two years, Russia has recorded a surplus on its current account of around 2.5% of GDP. For as long as Russia can continue to export large volumes of oil, this is unlikely to change. Russia’s oil and gas revenues jumped by 26% last year to $108 billion even as daily oil and gas condensate production declined in 2024 by 2.8%, according to Russian government officials cited by Reuters. Despite remaining the world’s most-sanctioned country in 2024, Russia exported a record 33.6 million tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) that year, which is a 4% increase from the previous year.

The Institute of International Finance (IIF) has forecast a decrease in Russia’s fiscal breakeven oil price (the amount to balance budget spending) to $77 per barrel by 2025, supported by a recovery in oil and gas revenues. At the same time, the external breakeven oil price (the price needed to balance the external current account), at $41 per barrel, is the second lowest among major hydrocarbon exporters. That means the current Urals oil price more than meets these breakeven points.

But none of this ‘war economy’ investment will support Russia’s long-term productivity growth. Russia’s war economy will revert to capitalist accumulation when the war ends. And the Russian economy remains fundamentally natural resource linked. It relies on extraction rather than manufacturing. War production is basically unproductive for capital accumulation over the long run.

Russia remains technologically backward and dependent on high-tech imports. Even with massive fiscal stimuli, it has yet to produce technologies fit for a competitive export market beyond arms and nuclear energy, with the former already sanctioned and the latter on the brink of being so. Russia is not a substantial player in any of the cutting-edge technologies, from artificial intelligence to biotechnology.

The demographic trough, the declining quality of university education and severed ties with international schools and a brain drain exacerbate these problems. The technological gap will likely widen, with Russia increasingly relying on Chinese imports and reverse engineering (copying). Russia’s potential real GDP growth is probably no more than 1.5% a year as growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population and low investment and productivity rates.

The Russian war economy is well placed to continue the war for several years ahead if necessary. But when the war is over, Putin may face a significant slump in production and employment. The underlying message is that the weakness of investment, productivity and profitability of Russian capital, even excluding sanctions, means that Russia will remain feeble economically for the rest of this decade.

The peace

President Trump has declared that he is seeking a peace settlement through direct negotiations with Russia. That would mean the end of US financial and military support for Ukraine. The current Ukraine leadership is opposing any deal that means the loss of territory and any veto on future membership of NATO. European leaders have declared that they will back Ukraine and continue to finance the war and provide military support.

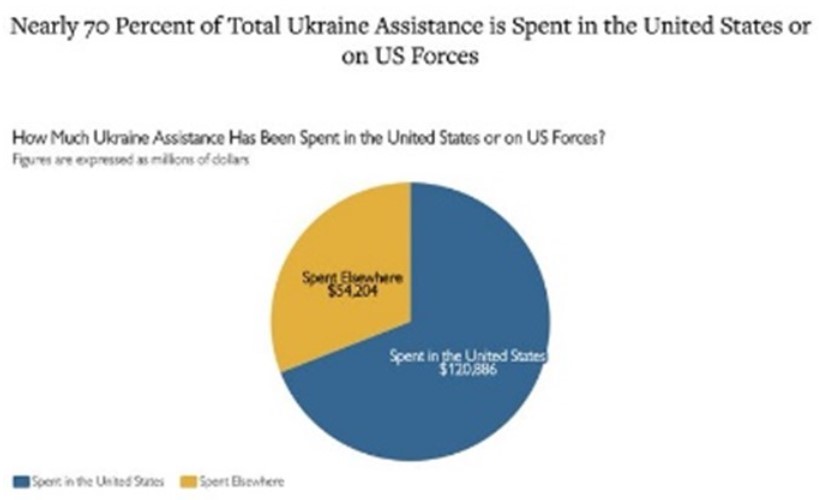

Trump wants back what the US government has spent on Ukraine up to now, as well as collateral for future spending to reconstruct the economy. He has complained about the huge transfers of funds to Ukraine unaccounted for. This is misinformation. The majority of the funds the US allocated for Ukraine stayed at home to fund the domestic defence industrial base and replenish US stockpiles. US arms manufacturers are making huge profits from this war.

Now Trump is demanding that Ukraine sign over 50% of its ‘rare earth’ mineral rights to the US in return for delivering the $500bn needed for post-war reconstruction. Trump: “I want them to give us something for all of the money that we put up and I’m gonna try and get the war settled and I’m try and get all that death ended. We’re asking for rare earth and oil, anything we can get.”

As US senator Lindsey Graham said: “This war’s about money…The richest country in all of Europe for rare earth minerals is Ukraine, two to seven trillion dollars worth…So Donald Trump’s going to do a deal to get our money back, to enrich ourselves with rare minerals…” The problem is that around half these deposits (worth some $10-12 trillion) are in Russian-controlled areas.

All this is just another indication that Ukraine’s assets are going to be carved up by the Western powers. Last month, Ukraine President Zelenskyy signed a new law expanding the privatisation of state-owned banks in the country. It follows the Ukrainian government’s announcement in July of its ‘Large-Scale Privatisation 2024’ programme that is intended to drive foreign investment into the country and raise money for Ukraine’s struggling national budget. Large assets slated for privatisation currently include the country’s biggest producer of titanium ore, a leading producer of concrete products and a mining and processing plant.

Ukraine envisaged privatising the country’s roughly 3,500 state-owned enterprises in a law of 2018, which said foreign citizens and companies could become owners. Hundreds of smaller-scale enterprises are now being privatised, bringing in revenues of UAH 9.6bn (£181m) in the past two years. This involves a seven-year sub-programme called SOERA (state-owned enterprises reform activity in Ukraine), which is funded by USAID with the UK Foreign Office as a junior partner. SOERA works to “advance privatization of selected SOEs [state-owned enterprises], and develop a strategic management model for SOEs remaining in state ownership.”

British capital is also licking its lips. Recently-published UK Foreign Office documents noted that the war provides “opportunities” for Ukraine delivering on “some hugely important reforms”. “The UK is hoping to reap benefits for UK firms from Ukraine’s reconstruction”, observes a report on British aid to Ukraine earlier this year by the aid watchdog, ICAI.

Putin’s invasion has driven the Ukrainian people into the hands of a pro free market, anti-labour government that will allow Western capital to take over Ukraine’s assets and exploit its diminished workforce. Maybe that was inevitable – from pro-Russian and pro-West oligarchs before the war, now to Western capital afterwards.

The war has not only destroyed Ukraine; it has seriously weakened the European economy as the costs of production have rocketed with the loss of cheap energy imports from Russia. But it seems that the European leaders want to continue the war even if Trump pulls out. They are desperately scrambling for funds to do that and to provide more military aid to the beleaguered Ukrainian government. Some leaders are proposing to send troops to Ukraine. So ‘war not peace’.

Just as bad is the decision of NATO and Europe’s mainstream leaders to double defence spending from about an average 1.9% of GDP by the end of the decade, supposedly to resist imminent Russian attacks if Putin gets a winning peace this year. This is ludicrously justified on the grounds that spending on ‘defence’ “is the greatest public benefit of all” (Bronwen Maddox, director of Chatham House, the international relations ‘think-tank’, which mainly presents the views of the British military state). Maddox concluded that: “the UK may have to borrow more to pay for the defence spending it so urgently needs. In the next year and beyond, politicians will have to brace themselves to reclaim money through cuts to sickness benefits, pensions and healthcare…In the end, politicians will have to persuade voters to surrender some of their benefits to pay for defence.” We get the same message from the leader of the winning party in the German election.

This will mean a huge diversion of investment from badly needed public services and benefits and from technological investment into unproductive and destructive arms production. That puts a huge uncertainty about Europe’s future as a leading economic entity through the rest of this decade and beyond.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here

Feature photograph is Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, from Wikimedia Commons, here.