By Michael Roberts

The UK government’s Spring statement on spending was as expected – really awful. First, Chancellor Rachel Reeves had to accept that the 2025 real GDP growth estimate will be half the rate previously forecast, halved to 1% from 2% by the government’s official forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

In addition, Reeves had to admit that the government’s inflation target rate of 2% a year would not be met until 2027 – and that assumes that Trump’s tariff measures don’t drive up costs in the meantime.

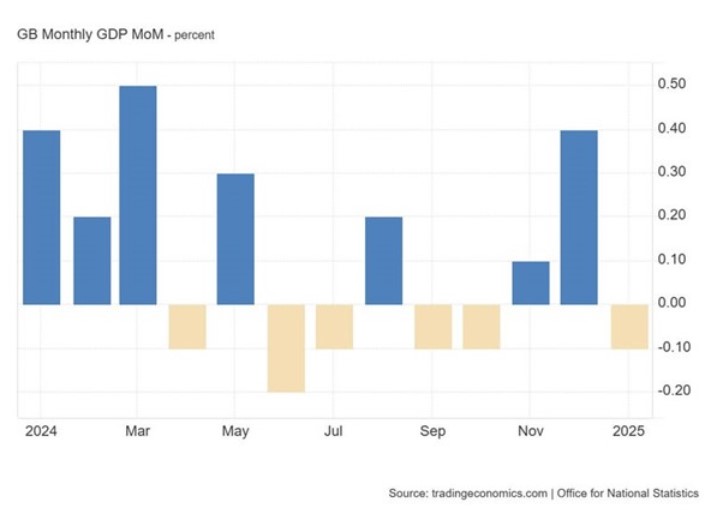

The UK economy remains in stagnation. Real GDP contracted 0.1% month-over-month in January 2025, worse than market expectations of a 0.1% gain. The largest downward contribution came from the production sector which fell 0.9%. The services sector also slowed to just a 0.1% rise.

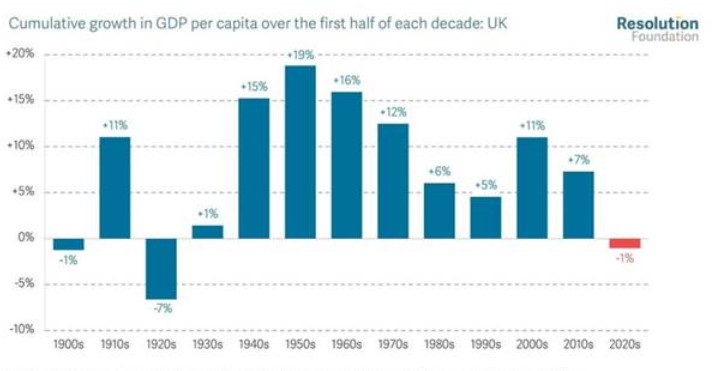

Real GDP per person growth in the UK in the first half of this decade is set to be the weakest of any comparable period in a century.

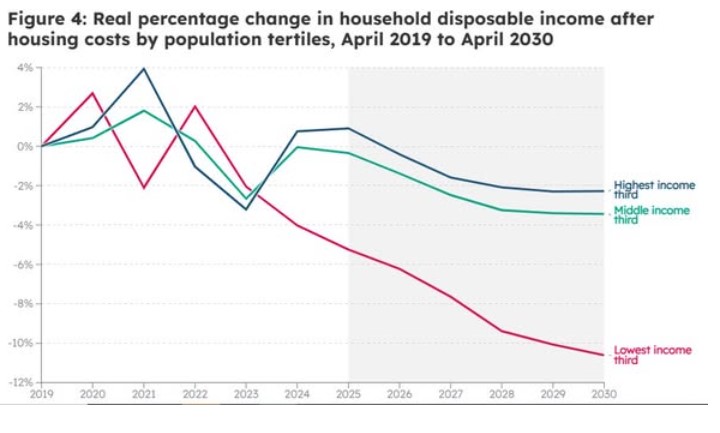

Despite this, Reeves sought to claim that the OBR has confirmed that real household disposable income will grow “at almost twice the rate” that had been anticipated in the autumn.

She said households will be “on average” £500 better off “under this government”. This claim is flatly denied by the Joseph Rowntree Trust in a new study that reckoned ALL British families will be worse off by the end of this decade, with those on the lowest incomes hit twice as hard as middle and high-earners, a new forecast suggests. That would mean the average real disposable income in the UK would have fallen for ten years.

“We estimate that average household disposable incomes after housing costs (hereafter ‘disposable incomes’) will remain £400 a year below 2020 levels in April. By April 2030 households will be a further £1,400 worse off on average than they are today, a 3 percentage point fall.”

The JRF forecasts that real gross earnings will fall by £700 a year between 2025 and 2030. This is due to firms passing on most of the costs of the recent increase to employer National Insurance Contributions (NICs) through lower nominal wages, smaller staff counts and higher consumer prices. Fiscal drag also continues to squeeze post-tax income through to 2028, as income tax thresholds have been frozen until 2028.

Middle- and higher-income households would have a fall in real disposable incomes of around 3% between 2025 and 2030, with real net earnings falling at the same time as housing costs rise. For the lowest income families, incomes are falling twice as fast as for the middle and the top, with a 6% fall in real disposable incomes between 2025 and 2030. These lowest income families will be £900 worse off by 2030, compared to today.

This Labour government has followed the previous Conservative government in imposing fiscal austerity – but this time on steroids. Reeves clams that there is a ‘fiscal hole’ between government revenues and spending now equivalent to £10bn a year, which must be filled. But this a hole that she has dug herself.

The government promised no income tax changes, including no rise in corporate profits tax. It opposed significant borrowing to bridge any gap. It has ignored calls for a wealth tax on the super-rich. Instead, it has introduced a range of welfare cuts that affect the poorest in Britain, although polling shows two-thirds of the British public (64%) support a wealth tax on those who have over £10m. A wealth tax of 2% a year on those owning more than £10m would raise £24bn a year, easily covering the so-called ‘fiscal hole’.

Instead, the cuts pour in. First, there was the cap on child benefit to two children per family. Then there was the abolition of winter fuel payments made to the elderly. And more recently, the government announced swingeing reductions in benefits to the disabled and those unable to work. The UK’s Resolution Foundation think-tank estimated that this would leave as many as 1.2mn people worse off by £4,300 a year by 2029, because they would not receive “daily living” payments. Tougher eligibility for personal independence payments (PIP) and incapacity benefits will mean some people now in line to receive £15,000 a year, excluding housing support, will instead receive just £5,400 — a drop of 64 per cent.

Ayla Ozmen, director of policy and campaigns at welfare charity Z2K, said three quarters of people on universal credit and disability support already struggled to afford the essentials. “Evidence from our advice services shows that those who will lose out include people with psychosis and double amputees,” she added.

This is a horrendous hit to the living standards of the poorest. Right now, three million UK households are £3,000 a year worse off than the poorest households in Germany and £1,500 a year worse off than the lowest earners in France. They are also poorer than people in the poorest parts of Slovenia (where average disposable income is almost £900 a year higher), Malta (£1,000 higher) and Ireland (£2,300 higher). So says a new report on British living standards by the NIESR.

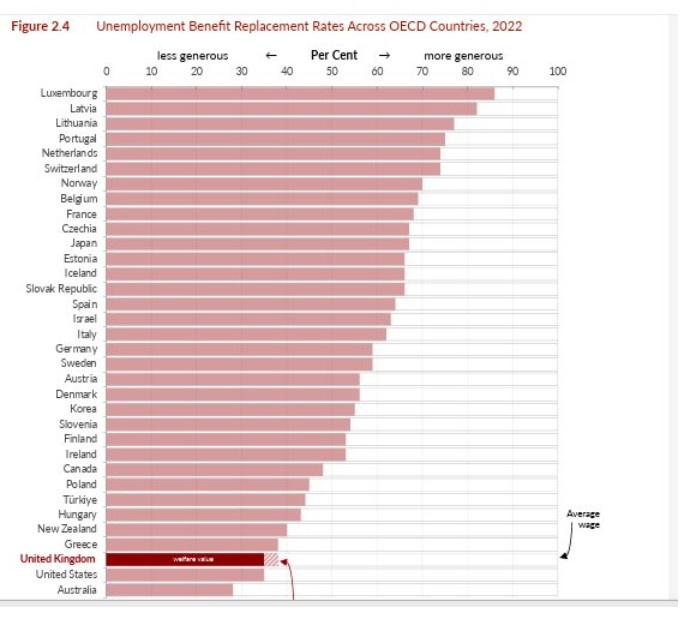

Districts in Birmingham were ranked as the poorest in the UK, according to the study, and below the poorest areas of Finland, France, Malta and Slovenia, it found. The UK now has some of the least generous welfare across countries in the OECD. Welfare payments covered the cost of essentials in only two of the past 14 years – both of them during the pandemic, after the £20 a week increase to Universal Credit.

And now Reeves plans a further cut in Universal Credit. The ‘health’ element in UC will be cut by 50% and then frozen for new claimants. Reeves also plans to cut central government spending by up to 15% over this parliament, thus halving any real rise each year, with big cuts, yet again, for local councils, prisons and the courts.

But there is more money to be spent in some areas, namely defence. The Starmer government with its arms race strategy in full blast has already announced a hike in defence spending from 2.3% of GDP to 2.5% by 2027 and onto 3% as soon as possible.

The first hike has been paid for by cutting foreign ‘aid’ to the poorest countries in the world. And the much-heralded National Wealth Fund for investment will now be allowed to make investments in defence ie to arms manufacturers. So less on productive investment and more on unproductive destructive investment. The reason the British economy is in such a mess is that productive investment growth is low, lower than in comparable economies.

The government says it is going to change that and boost investment and economic growth. But its plan to do so rests entirely on encouraging the capitalist sector to increase spending. Apparently this will be done by ‘de-regulating’ the economy – in effect ending environmental and climate controls, ending restrictions on monopolies and a free hand for the financial sector to do what it wants.

It was ‘light-touch’ regulation of the City of London that was the mantra of the last Labour government under Blair and Brown. Now it is doubled down on by Starmer and Reeves. According to Reeves, the City of London is the ‘crown jewel of the British economy and the main generator of growth’, not a centre of fictitious capital waiting for another accident to happen, as in 2008-9.

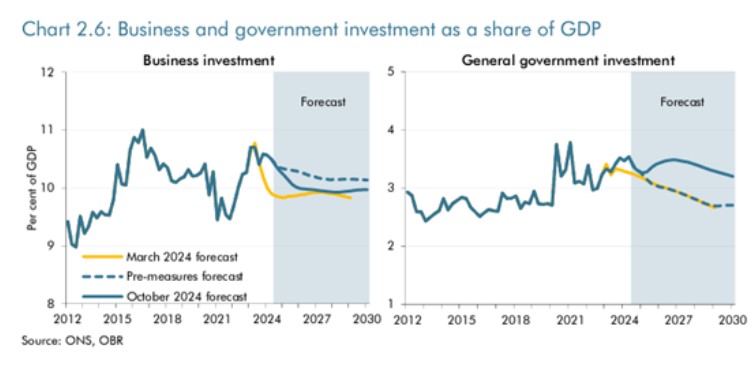

Through the mist of the government claims, the OBR finds that business investment to GDP, the lowest in the G7 at about 10%, will be little changed by the end of this parliament and government investment will be lower at the end of the Labour government’s term than at the start.

Labour’s policy to boost growth is to get rid of ‘planning’. Take housing. Reeves and deputy prime minister Rayner claim that de-regulating local planning regulations will take house building to a 40-year high (which is not actually saying much).

But their measures really open the door for private developers like BlackRock and landlords to build, sell and rent homes at unaffordable levels. So-called affordable homes are not that at all – at 80% of the market rate, where house prices have risen to nine times average wages in England and Wales, Hardly any ‘social housing’ for those in need is promised.

Reeves says she has to make these cuts in government spending to ‘fill’ her fictional fiscal hole and to control fast-rising government debt. It’s true that government debt to GDP is rising faster in the UK than in the rest of the G7 or Europe. But that is because economic growth is so weak and interest costs on debt are so high as a result of inflation.

The UK now spends more than £100bn a year on debt interest – a postwar high. This is money straight into the hands of the banks and financial institutions, paid for by welfare cuts. So the Labour government has decided to keep the financial sector happy with fiscal austerity and hope that economic growth will emerge from deregulation.

There are to be no taxes on the rich and the corporate sector. There is to be no public takeover of the productive sectors of the economy; nor the financial sector; nor the big investment funds. There is to be no public ownership of the corrupt energy and water utilities. The scandal of these privatized utilities is there for all to see, where shareholders have got billions in dividends, while debt and utility prices rise. The total collapse in the water infrastructure has reached the point where the UK’s water supply, rivers and beaches are no longer safe to drink or touch. Meanwhile, Britain’s roads are falling apart with unfilled potholes to the tune of £17bn to fix.

So yet more misery for most British households – Spring has not come, the Winter will continue.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.

Ever since Margaret Thatcher got elected in 1979 the British electorate have been told that prosperity will come from growth triggered by regulation. This was the policy of Thatcher and Major, then of Blair (and maybe Gordon Brown), continued in their own ways by Cameron, May, Johnson, Truss and Sunak. Now Starmer is beginning to tread the same sad, failed road. But has any of this reregulation delivered? The country is poorer and more polarised than ever and its industries are a shadow of what they were in 1979. Back then we had multiple car factories, railway and rolling stock industries, wire manufacture and engineering, steel…now almost all gone. Without those industries how can we find good quality employment for young people, and how can we pay for our public services? So the result of ‘growth through deregulation’ has been a desert.