By Michael Roberts

It’s not April Fools day (April 1). But it might as well be, as later today US President Donald Trump announces another barrage of tariffs on imports into the US, in what Trump calls ‘Liberation Day’, and what America’s voice of big business and finance, the Wall Street Journal, has called “the dumbest trade war in history.”

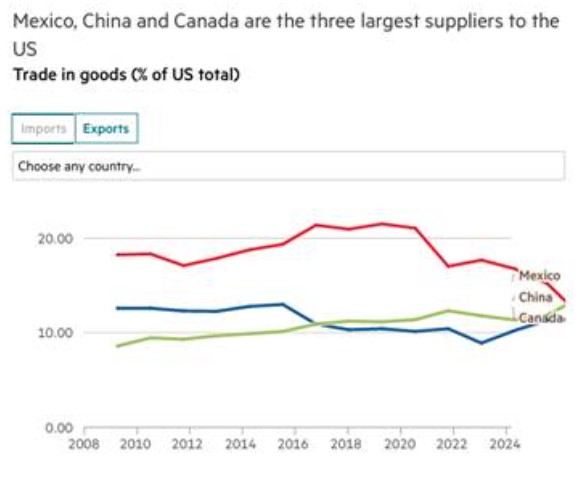

In this round, Trump is raising tariffs on imports from countries that have higher tariff rates on US exports, ie so-called ‘reciprocal tariffs’. These are supposed to counter what he views as unfair taxes, subsidies and regulations by other countries on US exports. In parallel, the White House is looking at a whole host of levies on certain sectors, and the tariffs of 25 per cent on all imports from Canada and Mexico which were earlier postponed are being now reapplied.

US officials have repeatedly singled out the EU’s Value Added Tax as an example of an unfair trade practice. Digital Services Taxes are also under attack from Trump officials who say they discriminate against US companies. By the way, VAT is not an unfair tariff as it does not apply to international trade and is solely a domestic tax – the US is one of the few countries that does not operate a federal VAT; relying instead on varying federal and state sales taxes.

Trump claims that his latest measures are going ‘liberate’ American industry by raising the cost of importing foreign goods for American companies and households, and so reduce demand and the huge trade deficit that the US currently runs with the rest of the world. He wants to reduce that deficit and force foreign companies to invest and operate within the US rather than export to it.

Will this work? No, for several reasons. First, there will be retaliation by other trading nations. The EU has said it would counter US steel and aluminium tariffs with its own duties affecting up to $28bn of assorted American goods. China has also put tariffs on $22bn of US agricultural exports, targeting Trump’s rural base with new duties of 10% on soyabeans, pork, beef and seafood. Canada has already applied tariffs to about $21bn of US goods, ranging from alcohol to peanut butter and around $21bn on US steel and aluminium products among other items.

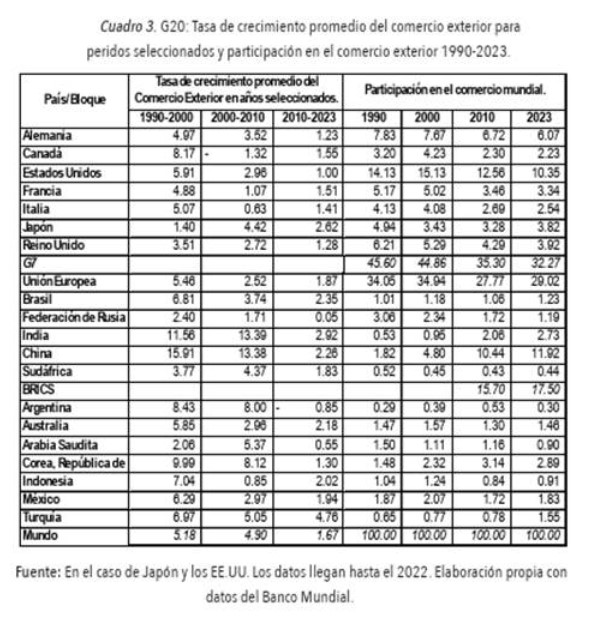

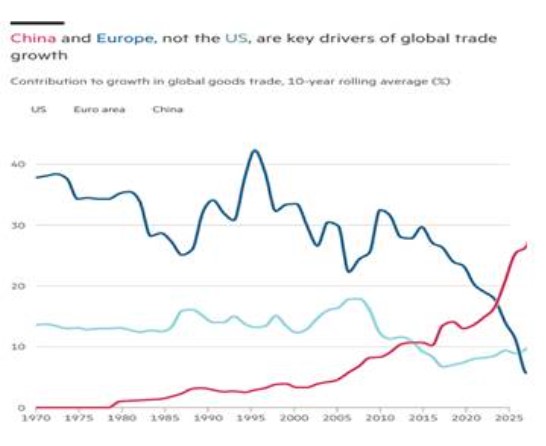

Second, US imports and exports are no longer the decisive force in world trade. US trade as a share of world trade is not small, currently at 10.35%. But that is down from over 14% in 1990. In contrast, the EU share of world trade is 29% (down from 34% in 1990) while the so-called BRICS [Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa] now have a 17.5% share, led by China at nearly 12%, up from just 1.8% in 1990.

That means non-US trade by other nations could compensate for any reduction in exports to the US. In the 21st century, US trade no longer makes the biggest contribution to trade growth – China has taken a decisive lead.

Simon Evenett, professor at the IMD Business School, calculates that, even if the US cut off all goods imports, 70 of its trading partners would fully make up their lost sales to the US within one year, and 115 would do so within five years, assuming they maintained their current export growth rates to other markets.

According to the NYU Stern School of Business, full implementation of these tariffs and retaliation by other countries against the US could cut global goods trade volumes by up to 10% versus baseline growth in the long run. But even that downside scenario still implies about 5% more global goods trade in 2029 than in 2024.

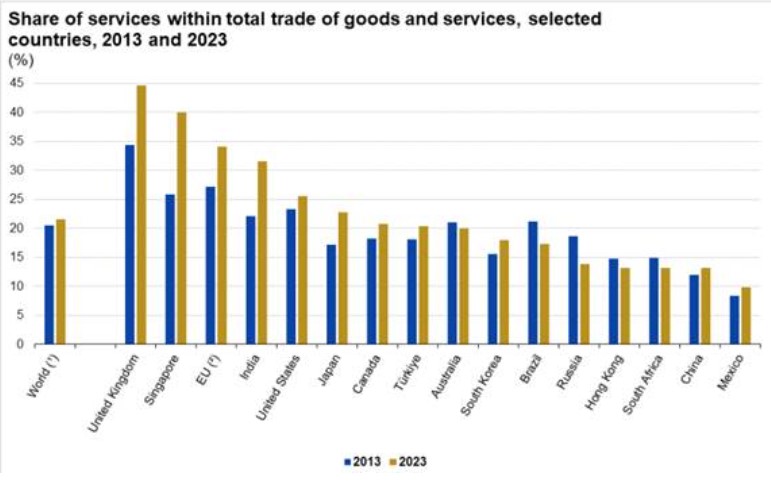

One factor that is driving some continued growth in world trade is the rise of trade in services. Global trade hit a record $33tn in 2024, expanding 3.7% ($1.2tn), according to the latest Global Trade Update by UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Services drove growth, rising 9% for the year and adding $700 bn – nearly 60% of the total growth.

Trade in goods grew 2%, contributing $500bn. None of Trump’s measures apply to services. Indeed, the US recorded the largest trade surplus for trade in services among the trading – some €257.5bn in 2023 — while the UK had the 2nd largest surplus (€176bn), followed by the EU (€163.9bn) and India (€147.2bn).

However, the caveat is that services trade still constitutes only 20% of total world trade. Moreover, world trade growth has fallen away since the end of the Great Recession, well before Trump’s tariff measures introduced in his first term in 2016, furthered under Biden from 2020, and now Trump again with Liberation Day. Globalisation is over, and with it the possibility of overcoming domestic economic crises through exports and capital flows abroad.

And here is the crux of the reason for the likely failure of Trump’s tariff measures in restoring the US economy and ‘making America great again’: it does nothing to solve the underlying stagnation of the US domestic economy – on the contrary, it makes that worse.

Trump’s case for tariffs is that cheap foreign imports have caused US deindustrialization. For this reason, some Keynesian economists, like Michael Pettis, have supported Trump’s measures. Pettis writes that America’s “long-term massive deficits tell the story of a country that has failed to protect its own interests.” Foreign lending to the US “force[s] adjustments in the U.S. economy that result in lower US savings, mainly through some combination of higher unemployment, higher household debt, investment bubbles and a higher fiscal deficit,” while hollowing out the manufacturing sector.

But Pettis has this back to front. The reason that the US has been running huge trade deficits is because US industry cannot compete against other major traders, particularly China. US manufacturing hasn’t seen any significant productivity growth in 17 years. That has made it increasingly impossible for the US to compete in key areas.

China’s manufacturing sector is now the dominant force in world production and trade. Its production exceeds that of the nine next largest manufacturers combined. The US imports Chinese goods because they are cheaper and increasingly good quality.

Maurice Obstfeld (Peterson Institute for International Economics) has refuted Pettis’ view that the US has been ‘forced’ to import more because of mercantilist foreign practices. That’s the first myth propagated by Trump and Pettis. “The second is that the dollar’s status as the premier international reserve currency obliges the United States to run trade deficits to supply foreign official holders with dollars. The third is that US deficits are caused entirely by foreign financial inflows, which reflect a more general demand for US assets that America has no choice but to accommodate by consuming more than it produces.”

Obstfeld instead argues that it is the domestic situation of the US economy that has led to trade deficits. American consumers, companies and government have bought more than they have sold abroad and paid for it by taking in foreign capital (loans, sales of bonds and inward FDI). This happened not because of ‘excessive saving’ by the likes of China and Germany, but because of the ‘lack of investment’ in productive assets in the US (and other deficit countries like the UK).

Obstfeld: “we are mostly seeing an investment collapse. The answer must depend on the rise in US consumption and real estate investment, to a large degree driven by the housing bubble.” Given these underlying reasons for the US trade deficit, “import tariffs will not improve the trade balance nor, consequently, will they necessarily create manufacturing jobs.” Instead, “they will raise prices to consumers and penalize export firms, which are especially dynamic and productive.”

As I have explained before, the US runs a huge trade deficit in goods with China because it imports so many competitively priced Chinese goods. That was not a problem for US capitalism up to the 2000s, because US capital got a net transfer of surplus value (UE) from China even though US ran a trade deficit. However, as China’s ‘technology deficit’ with the US began to narrow in the 21st century, these gains began to disappear. Here lies the geo-economic reason for the launching of the trade and technology war against China.

Trump’s tariffs will not be a liberation, but instead only add to the likelihood of a new rise in domestic inflation and a descent into recession. Even before the announcement of the new tariffs, there were significant signs that the US economy was slowing at some pace. Already, financial investors are taking stock of Trump’s ‘dumbest trade war in history’ by selling shares. America’s former ‘Magnificent Seven’ stocks are already in a bear market, ie falling in value by over 20% since Xmas.

The economic forecasters are lowering their estimates for US economic growth this year. Goldman Sachs has raised the probability of a recession this year to 35% from 20% and now expects US real GDP growth to reach only 1% this year. The Atlanta Fed GDP Now economic forecast for the first quarter of this year (just ended) is for a contraction of 1.4% annualised (ie -0.35% qoq). And Trump’s tariffs are still to come.

Tariffs have never been an effective economic policy tool that can boost a domestic economy. In the 1930s, the attempt of the US to ‘protect’ its industrial base with the Smoot-Hawley tariffs only led to a further contraction in output as part of the Great Depression that enveloped North America, Europe and Japan. The Great Depression of the 1930s was not caused by the protectionist trade war that the US provoked in 1930, but the tariffs then did add force to that global contraction, as it became ‘every country for itself’. Between the years 1929 and 1934, global trade fell by approximately 66% as countries worldwide implemented retaliatory trade measures.

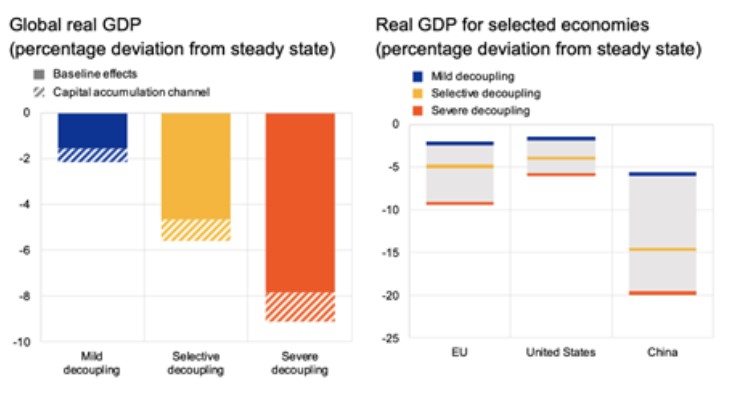

More and more studies argue that a tit-for-tat tariff war will only lead to a reduction in global growth, while pushing up inflation. The latest reckons that with a ‘selective decoupling’ between a (US-centric) West bloc and a (China-centric) East bloc limited to more strategic products, global GDP losses relative to trend growth could hover around 6%. In a more severe scenario affecting all products traded across blocs, losses could climb to 9%. Depending on the scenario, GDP losses could range from 2% to 6% for the US and 2.4% to 9.5% for the EU, while China would face much higher losses.

So no liberation there.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.

Feature picture from Wikimedia Commons, here