By Andy Ford, Warrington South CLP member

A hundred years have passed since the Mongolian Revolution. Mongolia at the turn of the 20th century was probably one of the most isolated places on earth. Although nominally part of the Chinese Empire it was ruled by chieftains owing allegiance directly to the Mongolian Khan who then collected tribute in the form of livestock to send to the distant Chinese capital. Apart from Chinese and Russian traders in the towns most of the population were nomadic pastoralists who lived by herding, and fully one third of the male population were monks living in temples and monasteries. Capitalist relations were almost entirely absent and there was no proletariat to speak of. And yet 20 years later, in 1921, the feudal theocratic regime was overthrown, creating the world’s second workers state; and from 1924 a planned economy was instituted. How and why did this happen?

It may appear to be the “very bowels of obscurity” but the Mongolian events of 1921 are interesting from the point of view of revolution and counter revolution in Siberia and the Soviet Union and in pre-capitalist states such as Ethiopia, Oman, South Yemen in the 1960s and 70s and even Afghanistan in modern times; but also the creation of Soviet Mongolia had a surprising indirect effect on the outcome of World War 2.

Mongolia before the Russian Revolution

Mongolia had always oscillated between independence from, and even attacks upon, successive Chinese Empires alternating with subjugation by them. The country lies beyond the area of cultivation of Chinese crops and always had a completely different economy and mode of governance. In 1911 the Chinese Empire collapsed in the course of the first Chinese Revolution and the Mongolian nobles in Urga (present day Ulan Baator) took the opportunity to assert their independence under a Buddhist ruler, the Bogdo Gegen or Bogdo Khan. Like the Dalai Lama in Tibet the Bogdo Gegen was a reincarnated ruler “found” as a boy by monks sent out to look for him.

Four years later, in 1915 Tsarist Russia and China agreed, in the Kyakhta Accord, to recognise Mongolian autonomy within the Chinese Republic but with freedom of Russian trade and influence. The more populated area of ‘Inner Mongolia’ was recognised as an integral part of China. The Mongolian leaders of Inner Mongolia preferred to be part of the more developed Chinese economy and there was a significant Chinese population there. Then and now there are actually more Mongolians living in Inner Mongolia than in Mongolia itself because the land can support far more people.

The Russian Revolution

In 1917 Tsarism in its turn collapsed. Seeing their chance the Japanese invaded the Russian Far East as one of the 21 armies of intervention and tried to proclaim a puppet pan Mongolian state stretching across Siberia as far as Lake Baikal, through Mongolia, and all the way to Tibet. The alarmed Chinese government exerted pressure on Japan who desisted and were later forced to withdraw their forces. The Chinese Republic began to consider reasserting its claims to Mongolia.

Meanwhile the Bolsheviks had renounced all the imperialist treaties and aspirations of Tsarism and in July 1919 they made a “Declaration to the People of Mongolia”. The Declaration put forward the core Bolshevik principle of the right of nations to self-determination and that this should be expressed by the will of the “free Mongolian people” and not by the theocratic power of the monarch.

However the Red Army was still far from Mongolia, battling Kolchak in the Siberian mountains and steppes and no-one in Mongolia made a reply. However the seed had been planted as subsequent events were to demonstrate.

China invades; Mongolia seeks allies

Seeing the Japanese withdraw and that Russian influence was effectively absent the Republic of China began to intrigue in Urga for Mongolia itself to renounce its own autonomy. They pressured the Bogdo Gegen to put a measure to the Mongolian assembly entitled “On the Recognition of Western Mongolia by the Government of China, and the improvement of the Welfare of the Mongolian Nation after the self-liquidation of its autonomy”. The lower house of the assembly categorically refused to pass the document at which point the Chinese sent General Hsu She-tseng to occupy Urga and subdue the country in October 1919. His brutal suppression of Mongolian liberty and culture awoke a wave of resistance and various secret groups began to emerge in the court of the Bogdo Gegen. As the Red Army fought its way across Siberia through 1920 these groupings began to consider Russian help to rid themselves of the Chinese occupation. A seven-man “Delegation of the Free Mongolian People”, led by Khorloogiin Choibalsan and Damdin Sukhebaator, was set up by the dissidents to go to meet the Red Army.

Soviet policy on Mongolia

Mongolia presented a problem to the Soviets. Although they had announced the right of Mongolia to self determination they had no interest in helping to dismember China by seizing parts of it. Their policy was all about triggering a further socialist revolution in China. To the Mongolians though, the Bolshevik withdrawal from the Tsarist Kyakhta Accord had the effect of delivering Mongolia over to Chinese rule. In China, the fact that the Bolsheviks had given up all Tsarist claims on Chinese territory had made a good impression on the Chinese public and the Bolsheviks had their eyes on a Chinese Revolution, as a much more significant event for the world revolution than a protectorate over the empty Mongolian steppe. For these reasons the first Bolshevik diplomat to pass through Mongolia on his way to Peking, in summer 1919, made no contact with any Mongolian representatives. Likewise when the Chinese visited Moscow in the autumn it was agreed not to discuss the “Mongolian question”.

But the Mongolian rulers were desperate. In March 1920 the Bogdo Gegen wrote three letters – to the governments of Japan, the United States and Soviet Russia – seeking their help in restoring Mongolian autonomy. The “Delegation of the Free Mongolian People” was smuggled out of Urga and by April had reached the Bolshevik command in Irkutsk. They carried with them a letter of authorisation under the seal of the Bogdo Gegen.

Initially the Bolsheviks in the person of I. Gapone, Secretary of the Siberian Bureau (‘Sibburo’) of the Bolshevik Central Committee did not welcome the Mongolian delegation. They saw Mongolia as a part of China and at most as a possible bridge to set up a Chinese revolutionary organisation which, like the Bolsheviks, would overthrow capitalism in China and also offer self determination to the various nationalities of the Chinese Empire. Intriguing with the Mongolians would only alienate the nascent Chinese revolutionaries.

Negotiations

Nevertheless discussions did begin. Gapone’s opening gambit was to map out a revolutionary programme for China, not Mongolia:

“I am deeply convinced that the Mongolian people will see very clearly with their own eyes that their enemy is not the working people of China, whose suffering is similar to their own, but that the real enemies are the ruling classes who exploit them and play on their on their ignorance. When they become aware of all this, the Mongolian workers will hold out their hands to the exploited masses of China and in one stoke throw down the terror that oppresses them.”

For their part the Mongolian delegation could not care less about the “exploited masses of China”: they needed money, weapons and maybe even the Red Army to free their country. They pointed out that the effect of the Soviets repudiating the Kyakhta Accord was not to give freedom to Mongolia but to return it to Chinese control. They began to see that some sort of social transformation of Mongolia would be necessary to attract Soviet support. They put forward an idea of an autonomous “Commune of the Steppe”. The Mongolian delegation was beginning to split along class lines.

In a letter to the Bolshevik leader I.N. Smirnov, entrusted by Lenin with task of “Sovietizing and pacifying Siberia”, Gapone identified three trends in the Mongolian delegation:

“The first…reflected the position of the high nobility and the church; the second was based on the small civil servants, the military and the small traders… and the third was based on the popular masses – the target of the national revolutionary party”.

In the end, the Mongolian delegation managed to agree on a compromise:

Reunification of the Mongolian territories, a position that would not suit either China or Russia.

To develop a “close liaison and contacts with Chinese revolutionary groups and organisations”

In exchange for which they could extend their sphere of influence over all parts of Mongolia

A future “Form of federation or autonomy, in relationship with China”

The Soviets set about procuring weapons, financial credits and other measures for the proposed revolutionary movement in Mongolia while also making progress in discussions with the third group of delegates who were gradually developing towards a Bolshevik position as they became familiar with the Bolshevik programme and could see before them the victories of the Red Army.

The Mongolian National Party is formed

By August the left delegates, led by Damdin Sukhebaator, later the Minister of War in the Mongolian Republic, had formed a party, and were won to a position of “The destruction of the feudal and theocratic regime of Mongolia and the establishment of the democratic regime” as the urgent tasks of the Mongolian National Party. They also called for the arming of party members and military training. When Gapone asked them if they still stood on the programme of the original letter from the Bogdo Gegen they repudiated it in favour of a democratic, not a theocratic state.

“After establishing a constitutional monarchy the party will destroy the oppression of the princes. The party will spread the propaganda of national-revolutionary ideas among the masses of the people, while disseminating European culture. In this way, the Party will prepare the ground for its intervention, with the final goal of destroying the existing feudal order. At this stage, the party will have in front of it only one opponent: the nobles of the Court.”

They also promised economic aid to Soviet Russia:

“The party will appoint an organ of mutual aid for Soviet Russia, which will coordinate its action with the Mongolian-Tibetan Section and related organizations, in order to supply Russia with beef and raw materials. In exchange for which Soviet Russia will set up in Mongolia factories and plants in Mongolia to produce, at the request of the National Revolutionary Party, products for everyday consumption.”

Future relations with a revolutionary China were put off to the future:

“In our opinion, after the victory of the two revolutions in China and Mongolia, when the state power is handed over to the hands of the working people then the National Revolutionary Party of Outer Mongolia will succeed without great effort to take and retain power.”

In revolutionary Moscow

The project therefore was of a Soviet Mongolia with the Bogdo Gegen as nominal Head of State offering economic aid to Soviet Russia and acting as a support on the borders of the USSR. Such an innovation in Soviet policy, of a communist constitutional monarchy on the steppes of Mongolia, could not possibly be agreed in distant Irkutsk and so a section of the Mongolian delegation was despatched to Moscow for discussions with the leaders of the world revolution.

The Mongolian delegate, “Comrade Rynchin” was invited to the Bolshevik Politburo, along with a Tibetan and a Kyrgyz delegate, to discuss the situation in the Far East with Lenin, Bukharin and Stalin. He pointed out the possibility of a theocratic Mongolia actually having more in common with the Manchurian warlords, the Japanese Empire or even the White Russian armies than with the Bolsheviks:

“If indeed, in the Chinese civil war, the reactionary party of Manchuria – led by Tse Yan Tso Lin and supported by the Japanese – gains the upper hand, then Mongolia will fall into the nefarious sphere of Japanese influence! Its feudal theocratic regime is likely to strengthen and then subdue the democratic movement. The Mongolian territory will then be exploited in order to organise counter-revolutionary bands against Soviet Russia.”

“Comrade Rynchin”, Elbeg Rynchino, had a chequered past, having started as a Mongolian nationalist author who then attached himself to the White Guard forces in the Russian Far East. For this reason he was treated with great suspicion in Irkutsk. He was only there as a translator, not even as a delegate. However he soon worked out the political realities and his position evolved rapidly towards support for a Soviet Mongolia. The Russian revolutionary government did not have the luxury of waiting to find fully developed Bolsheviks in the wilds of Siberia – they had to work with whoever would work with them.

In the event the Politburo supported his ideas and offered 80,000 roubles, about one third of the money budgeted for the whole of China, to the Mongolian cause.

White Terror in Mongolia

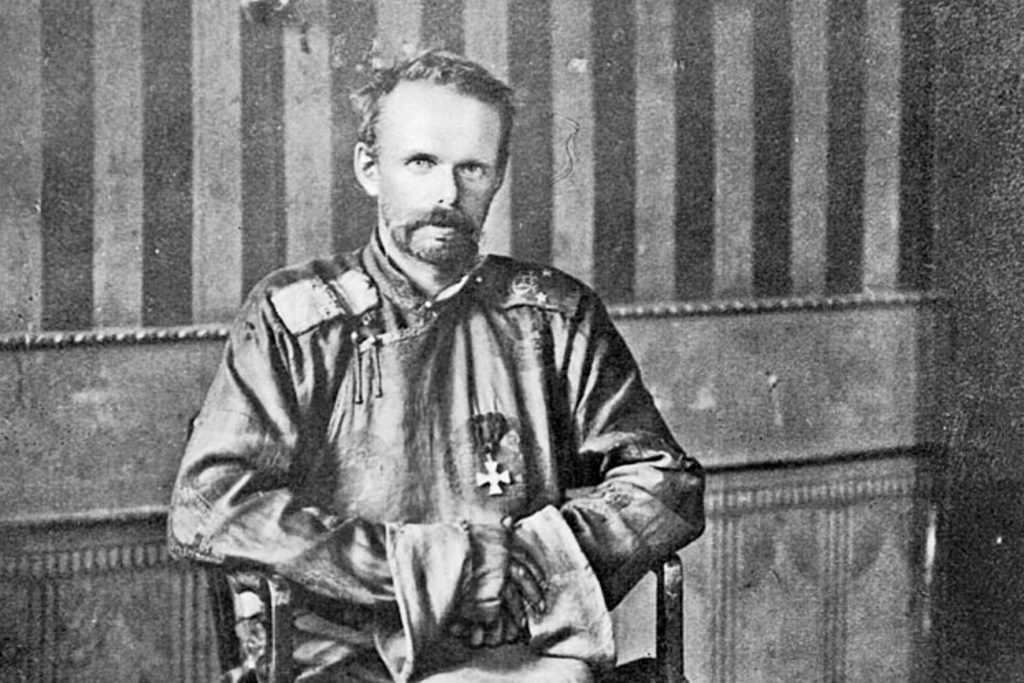

Very shortly after, as if in confirmation of Rynchin’s warning, Mongolia was invaded in autumn 1920 by Ungern-Sternberg and his ‘Asian Division’ composed of 4,000 Russians, and 2,000 native Siberian cavalry. This force was armed and partly officered by the Japanese. Even by the standards of the Russian Civil War, the crazed and sadistic Ungern-Sternberg was notorious – for his treatment of civilians, and of Red prisoners. In the Tsarist army he had been considered mentally unstable and was in a military prison when the 1917 revolution came.

By February 1921 he had occupied Urga promising to liquidate all Mongolians who had co-operated with either the Chinese occupation or the Soviets. His proclamation of 21st May 1921 further announced an intention similar to Hitler’s in WW2, “…to exterminate commissars, communists, and Jews with their families…in the struggle with the defilers of Russia there can only be one punishment – the death penalty in various degrees”.

The Bogdo Gegen, who had been imprisoned during the Chinese occupation, was freed by the White Guards, and proclaimed himself leader of an independent Greater Mongolia, including both Inner and Outer Mongolia, with Ungern-Sternberg as his ‘military advisor’. The feudal theocratic regime thereby collapsed, as predicted, into the arms of bloody reaction, backed by Japanese imperialism. The Asian Division began a campaign of cruel and chaotic terror against any opposition, real or imagined.

July 1921 – Power passes to the revolutionaries

Meanwhile the Mongolian People’s Party assembled its forces on the northern border and proclaimed itself as the government of a Mongolian People’s Republic on March 19th 1921. White Army general Ungern-Sterberg, “never a man to await attack” (in the words of E.H. Carr), launched his forces at the Red Army on the border. He was defeated and in the retreat his army mutinied and handed him over to trial and execution by the Soviet authorities – not unexpectedly as he was known for being only slightly less cruel to his men than to his opponents.

The joint forces of the Mongolian People’s Party led by Damdin Sükhbaatar and the Red Army entered Urga in July 1921 and on the 5th November Mongolian independence was recognised by the Soviet Union (although by nobody else). The old regime had been swept away. When the time came it was so rotted from within it had no option but outside support, and no-one to fight for it.

Soviet Mongolia

The Bogdo Gegen was kept in place as Head of State but with Sukhbaator as Minister of War and in control of the army. A Buddhist monk, Dogsomyn Bodo, was Prime Minister. In some senses therefore this was the democratic stage of the Mongolian Revolution. In 1924 the Bogdo Gegen died of cancer and the Mongolian communists refused to allow a successor to be identified. They then began a process of social transformation of the country.

A full history of Soviet Mongolia is something for another day but in summary Mongolia became a Soviet Union in miniature. Sukhebaator died early, in 1923, and like Lenin, the country’s main city was named after him and he was elevated almost the level of a national totem or guiding spirit. His body was even at a later date embalmed and put on display. His widow Yanjmaa, like Krupskaya or Alexandra Kollontai, went on to play a prominent role in the state after her husband’s death and did much to raise the status of women from the frankly medieval level of pre-revolutionary Mongolia. Choibalsan, unfortunately, went on to be ‘the Mongolian Stalin’ and presided over economic zig zags and political purges, before dying himself in a Moscow hospital in 1952, almost certainly as a result of one of Stalin’s ’botched operations’.

Battle of Kalkhin Gol 1939 – Japan defeated

Despite the crimes of Stalinism in Mongolia the country did develop and an efficient army was created, armed with Russian weapons. When, in 1939, Japan and their Manchurian puppets attempted to take a slice of disputed Mongolian territory they were decisively defeated by Mongolian and Red Army troops in the Battle of Khalkin Gol. The significance of this obscure battle on the outcome of the Second World War lies in the fact that it led to a firm decision by the Japanese imperialists to avoid conflict with the USSR. Instead they drove into the European colonies of Indo-China, Malaysia, Burma and the Dutch East Indies. This allowed Stalin to move fresh Siberian troops to the defence of Moscow in the winter of 1941 to stave off a German occupation of the capital – which could have resulted in a Nazi victory on the Eastern Front.

The Mongolian Revolution in retrospect – summary

The Bolsheviks had hoped that Mongolia would be the first step in spreading the world revolution to the east; instead it marked the final battle of the Russian Civil War. No other country overthrew capitalism until the Eastern European states in 1946-48.

Although Mongolia clearly lacked the material basis for socialism, so did the neighbouring regions of Soviet Siberia such as the Buryat Mongol Republic, Tannu Tuva and Yakutia. But in alliance with a healthy Soviet Union they could have developed directly to socialism, as had been envisaged by Marx in his writings on Russia. However workers soviets never existed in Mongolia, and nor could they given the conditions at the time. So Mongolia as perhaps the world’s first ‘deformed workers state’.

Some writers have said the Bolsheviks should have left the Mongolians to determine their own fate in keeping with the principle of self determination. But this would have meant allowing a development similar to Finland in 1918 where giving the Finns ‘self determination’ resulted in a bloodbath of the workers and peasant leaders. The Bolsheviks would then have been left with a hostile White Guard state on their far eastern border armed and financed by Japanese imperialism.

Despite Choibalsan’s economic zig-zags and purges through the 1920s and 30s, the economy did develop but only at a tremendous human and cultural cost. An efficient army was created that was able to repel various Chinese warlords throughout the 1930s and defeated the Japanese Imperial Army in 1939 with assistance from the Red Army.

‘Soviet’ Mongolia endured for 70 years but it could not withstand the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The restoration of capitalism in the 1990s led to an unprecedented collapse in economic output, life expectancy and birth rate. The capitalist Mongolia that emerged from the chaos of restoration is one which is dependent on the export of raw materials, mainly to China, and is subject to horrendous environmental degradation and exploitation as a result of unregulated mining.

Sources and further reading

A.S. Jelezniakov ‘L’annee 1920 – La naissance du Communisme mongol’ , Cahiers Leon Trotsky Volume 80 March 2003 (Marxists Internet Archive)

E.H. Carr ‘The Bolshevik Revolution Volume3’

Victor Serge “The Death of Ivan Nikitich Smirnov’ (Marxists Internet Archive)

James Palmer; `The Bloody White Baron`